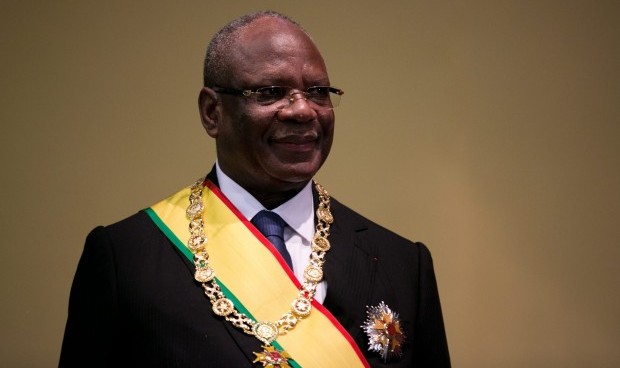

Mali’s new President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, former Prime Minister and President of the National Assembly, smiles as he is sworn in to office in Bamako, Mali, 04 September 2013. (EPA/Tanya Bindra)

Bamako, Reuters—Mali’s new president, Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, pledged to stamp out corruption and bring peace to the turbulent north as he was sworn in on Wednesday, 18 months after a coup and rebel uprising plunged the gold exporter into chaos.

The former prime minister won last month’s runoff vote by a landslide—the first election since soldiers took the capital and Tuareg separatists and Islamist insurgents seized the northern half of the country.

Keita told a packed auditorium he would unite the fractured country—once seen as a haven of stability in West Africa—and thanked France for its military intervention that drove al Qaeda-linked fighters out of the vast desert territory.

France did not tackle the separatists—saying their uprising was a domestic matter—and Mali’s government has already promised to start talks with the Tuaregs, currently clustered in their remote northeastern stronghold of Kidal.

“National reconciliation is our most pressing priority,” said Keita, wearing a yellow presidential sash across a business suit. “From tomorrow, we will take appropriate steps to bring a lasting peace to break this cycle of rebellions in the north.”

Light-skinned Tuaregs, demanding greater autonomy from the black African-dominated southern capital Bamako, have launched four rebellions since independence from France in 1960.

Previous peace deals promising development to the region have been undone by rampant corruption and a lack of trust.

Many in the populous south are bitterly opposed to ceding more autonomy and funds to the northerners, who they blame for their country’s implosion last year.

Keita, known by his initials IBK, has promised to convene a national convention to discuss devolution of authority to the regions, both in the north and south.

Keita also faces a daunting task in reviving Mali’s economy, which shrank by 1.2 percent last year. Mali is sub-Saharan Africa’s third largest gold exporter.

His hand will be strengthened by 3.25 billion euros ($4.28 billion) in reconstruction aid pledged at a conference in Brussels in May.

Advocacy groups have urged Keita to tackle deep-rooted corruption. Junior military officers said widespread anger over graft was one of the triggers of their March 2012 coup.

“Mali stands at a crossroads,” said Corinne Dufka of Human Rights Watch. “President Keita’s actions—or inactions—could usher in greater respect for human rights or a return to the problems that caused Mali’s near-collapse last year.”

Keita, who earned a reputation for toughness in crushing student protests as prime minister during the 1990s, pledged to restore the rule of law.

“I will bring an end to impunity,” he said. “I will fight corruption tirelessly. No-one will be able to illicitly enrich themselves at the expense of the Malian people.”

Analysts have called on Keita to use the mandate from his overwhelming victory in the August 11 election to appoint a cabinet of capable technocrats, rather than political allies.