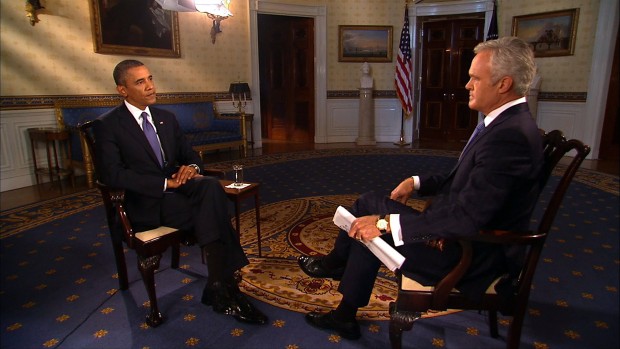

In this image from video provided by CBS News, CBS Evening news anchor Scott Pelley interviews President Barack Obama in the Blue Room of the White House in Washington, Monday, Sept. 9, 2013. (AP Photo/CBS News)

But Obama, speaking in a series of television interviews, remained skeptical and pushed ahead to persuade a reluctant and divided Congress to back potential US action, saying the threat of force was needed to press Syria to make concessions.

In an extraordinary day of diplomacy over the war-wracked Middle Eastern country, Russia seized on an apparently throwaway public remark by US Secretary of State John Kerry to fashion a new approach that could save face for all sides.

“My preference consistently has been a diplomatic resolution to this problem,” Obama told NBC. He said an agreement for Assad to surrender his chemical weapons to international control would not solve the “underlying terrible conflict inside of Syria.”

He added: “But if we can accomplish this limited goal without taking military action, that would be my preference.”

“It’s possible that we can get a breakthrough,” Obama told CNN, although there was a risk that it was a further stalling tactic by Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, who has presided over more than two years of civil war.

“We’re going to run this to ground,” he said. “John Kerry and the rest of my national security team will engage with the Russians and the international community to see, can we arrive at something that is enforceable and serious.”

Obama has argued that Assad, fighting to continue his family’s four-decade rule, must be punished for what Washington says was a poison gas attack on rebel areas that killed over 1,400 people on August 21.

Human Rights Watch said evidence strongly suggested Syrian government forces were behind the attack. It said in a report issued in New York that the type of rockets and launchers used in these attacks suggested weapon systems only in the possession of the Syrian government’s armed forces.

In Congress, Democratic Senate leader Harry Reid pushed back a Senate test vote on possible US strikes that had been scheduled for Wednesday as lawmakers evaluate the Russian plan.

The vote is still expected this week, and a more contentious vote would later be held in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

The dramatic diplomatic twist in weeks of high-tension international wrangling came when Kerry was asked by a reporter during a visit to London whether there was anything Assad’s government could do or offer to stop a US military strike.

“Sure. He could turn over every single bit of his chemical weapons to the international community in the next week—turn it over, all of it without delay and allow the full and total accounting. But he isn’t about to do it and it can’t be done.”

The State Department later said Kerry had been making a rhetorical argument about the impossibility of Assad turning over chemical weapons, which Assad denies his forces used.

Less than five hours later, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said he had put what sounded like Kerry’s proposal to his visiting Syrian counterpart during talks in Moscow. Walid Al-Moualem said Damascus welcomed the Russian initiative—while not spelling out whether Syria would, or even could, comply.

Iran supports Russia’s offer to work with Syria to put its chemical weapons under international control, the Iranian foreign ministry said.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has blocked UN action against Assad and says Obama would be guilty of unlawful aggression if he launches an attack without UN approval.

Lavrov said: “If the establishment of international control over chemical weapons…makes it possible to avoid strikes, then we will immediately get to work with Damascus.”

He said Russia was also urging Syria to eventually destroy the weapons and become a full member of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

Rebels fighting Assad’s forces on the ground, where hundreds are being killed by conventional bullets and explosives every week, dismissed any such weapons transfer as impossible to police and a decoy to frustrate US plans to attack.

Kerry later called Lavrov to tell him that while his remarks had been rhetorical and the United States was not going to “play games,” if there was a serious proposal, then Washington would take a look at it, a senior US official said.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon took up the same theme, saying that he might ask the Security Council to end its “embarrassing paralysis” over Syria and agree to act.

Asked about Lavrov’s proposal, Ban said: “I’m considering urging the Security Council to demand the immediate transfer of Syria’s chemical weapons and chemical precursor stocks to places inside Syria where they can be safely stored and destroyed.”

Britain and France, permanent members of the Security Council with Russia, China and the United States, both tentatively welcomed the Russian proposal.

UN chemical weapons inspectors were in Damascus at the time of the August attack, which Assad and Putin have blamed on rebel forces. Ban said that if the evidence they were able to gather—after lengthy bargaining over their movements with Syrian officials—proved the use of toxins, the world must act.

Syria, which has never signed a global treaty banning the storage of chemical weapons, is believed to have large stocks of sarin, mustard gas and VX nerve agents—the actual use of which is banned by a 1925 treaty to which Damascus is a signatory.

White House officials were skeptical of the feasibility of the Russian proposal. Syria is a battleground where access for foreign experts would be dangerous. And it would be very hard to verify whether all sites had been sealed.

Years of cat-and-mouse maneuvering between U.N. weapons inspectors and Saddam Hussein in neighboring Iraq shows how difficult it might be to enforce any arms control orders on a timetable that would satisfy Washington in the midst of a war.

Qassim Saadeddine, a rebel commander in northern Syria and a spokesman for the Supreme Military Council of Assad’s opponents, said: “It is a trap and deceitful maneuver by the Damascus regime and will do nothing to help the situation.

“They have tons of weapons hidden that would be nearly impossible for international inspectors to find.”

Putin, however, would see major diplomatic advantages to any plan that bolstered Russia’s role in brokering international settlements and thwarted strikes in which Obama may have French military support.

Obama said he was pressing ahead to secure approval in Congress for limited and targeted strikes against Syria, aware of the strong opposition of most Americans after a decade of wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

“I don’t think that I’m going to convince…the overwhelming majority of the American people to take any kind of military action, but I believe I can make a very strong case to Congress, as well as the American people, about why we can’t leave our children a world in which other children are being subjected to nerve gas,” he said on PBS.

Kerry said he was confident of the evidence that the United States and its allies had presented to support their case that Assad’s forces used poison gas, a charge that Assad denies.

But Kerry said he understood wariness among Americans lingering from accusations against Saddam that led to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and later proved to be false.

A survey by the newspaper USA Today found majorities of both houses remained uncommitted—reflecting broad and growing public opposition to military action.

A Reuters/Ipsos poll on Monday showed Americans’ opposition to a US military strike against Syria was increasing. The poll, conducted September 5 to 9, indicated that 63 percent of Americans opposed intervening in Syria, up from 53 percent in a survey that ended August 30.

Tapping into concerns in the West about the role of Islamist militants in the rebel forces, Syrian Foreign Minister Moualem said: “We are asking ourselves how Obama can…support those who in their time blew up the World Trade Center in New York.”

Assad himself warned of reprisals—if he were attacked Americans could “expect every action”, he told CBS television.

Brent crude oil futures sank more than 2 percent on Monday, as the prospect of a wider war in the Middle East appeared to recede. “This has thrown some sand into the wheels of military preparation in the US,” said Michael Lynch of Strategic Energy & Economic Research.

“At the very least, it means the debate is going to be stalled while we wait and see if it works out.”

Inside Syria, government forces launched an offensive to wrest back control of a historic Christian town north of Damascus on Monday, activists said. In the past six days, the town of Maaloula has already changed hands three times between Assad’s forces and rebels, some of whom are linked to Al-Qaeda.