How Viable Is the “Chinese Model” ?

In a recent visit to China, the former American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger asked his guide to arrange a meeting with” my old friend Jiang Zemin.”

The guide responded with a dismissive gesture: That person is no longer available.

“That person”, of course, had been China’s President for a decade, before being eased out of office in one of those mysterious palace coups that the country has experienced since the 1970s.

The system that makes Jiang Zemin a non-person almost overnight was shaped by the late Deng Xiaoping who ruled China with an iron fist for almost two decades without occupying the highest positions of state.

Under that system the top leadership of the Chinese Communist Party undergoes a thorough purge every 10 years. Since then Hua Kuo-feng, Hu Yabang and, more recently Jiang Zemin, have successively bowed out of stage at the head of tens of thousands of party and government officials throughout the country.

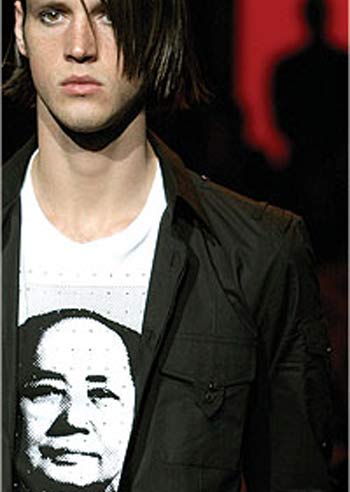

Deng was more than the mere architect of palace coups. He was also the father of what is known as “The Chinese Model” which consists of combining an authoritarian political regime, symbolised by one-party rule, with a laissez-faire capitalist economic system of the type that Guizot had preached in France in the 1830s.

At first glance “The Chinese Model” appears to be a success. Politically, it has produced a level of stability unknown in most other Third World countries. Economically, it has generated growth, at times topping the 10 per cent per annum, and transformed China from a largely rural nation into a major player in international trade. Last year China emerged as the world’s fifth largest economic power. And, if the extrapolations prove correct, it will become the largest, ahead of the United States, by 2020.

“The future will be Chinese,” predicted Alain Peyrfitte, one of the first Europeans to write about the rising Asian colossus. President Hu Jintao goes even further: The best is yet to come!

Anyone who visits Shanghai, where more than 1500 skyscrapers, 10 times as many as in New York, reach for the clouds, cannot but agree.

But what if this colossus has feet of clay? What if the so-called “Chinese Model” consists of nothing but brief, though impressive, fireworks of history?

Such questions might sound impertinent about an economy that is projected to double in size every seven years.

And, yet, some of these questions are being posed, albeit in private conversations, in Beijing itself. And, on rare occasions, they even find a measure of public airing. One instance came last January when The China Youth Daily published an essay in its weekly supplement “Freezing Point”.

Bearing the drab title of “Modernisation and Historic Textbooks”, the article, by Yuan Weishi, a university teacher, suggested that the Qing Dynasty officials opened China to foreign invasion and domination by mismanaging the economy some two centuries ago.

Read by the profane the article might appear as nothing but a polemical account of an episode in history. But a more careful reading reveals a roundabout critique of China’s present-day economic policies, ending with the dire conclusion that the country’s increasing reliance on foreign trade might, once again, undermine its independence.

Not surprisingly, the ruling Communist Party reacted by temporarily closing down the newspaper, canceling its supplement, and firing its editorial staff.

What was surprising, however, was that the protests provoked by the crackdown. These included dozens of former party officials, academics and intellectuals, who signed an open letter denouncing censorship. The signatories have suggested a more open discussion of economic policies that have always been made behind closed doors and by a handful of politicians and their technocratic advisors.

But what are the weaknesses of “The Chinese Model”? According to most experts at least 10 could be identified:

• China’s economic growth is input driven. This means that massive amounts of labour, capital and raw material are used in volumes that might not be sustainable for ever.

• Chinese policymakers confuse growth with development. The Chinese economy is diversified laterally without acquiring depth. The product range it offers is still five per cent of what the Dutch economy, for example, has to offer.

• In a sense China offers nothing but a new version of the monoculture economies; it exports only one thing: cheap labour.

• By keeping its prices low and its currency cheap, China is, in fact, subsidising consumers on the rich countries.

• China is becoming increasingly dependent on foreign capital, technology, energy resources, and markets. This prevents the creation of an economy geared to meeting the needs of the domestic market: food, health care, education and housing.

• China today has created the model that the Europeans wanted to impose on it in the 19th century. This consists of dividing the country into two entities: the coastal province that have been absorbed into the global market, and the hinterland which remains rural and closed.

• China is largely a subcontractor for major industrial powers, especially the United States, the European Union, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan. Its role is to host old-style manufacturing at a time that the more advanced economies enter the post-industrial era.

• The label “Made in China” does not hide the fact that China does not own any of the 5000 major brands that dominate the global market. Nor does China own a single major bank, insurance company, or brokerage firm capable of operating at regional, not to mention global, levels.

• China spends much of its foreign earnings on buying US Treasury bonds, thus helping cover the saving deficiency of the American economy. That, in turn, deprives the country of resources needed to raise living standards for the 800 million or so “ below poverty” citizens in the hinterland.

• The presence of a reservoir of cheap labour, estimated at around 200 million “job-seekers” at any given time, may be an asset in the short-run because it keeps labour costs low, especially in the absence of trade unions. In the medium and long-term, however, it could destabilise the entire system.

In addition to all that, China faces at least three political vulnerabilities.

The first concerns the future of decision-making. Can the current one-party system be sustained for long? Or , as there are signs already, it will be challenged by the emerging middle classes and yuppies that, having tasted material wealth, are bound to demand a share of political power?

The second political vulnerability stems from the first. If the political system is to be opened up it might lead to a shift of power from the coast to the hinterland thus threatening the very economic model which has created the recent “ Chinese Miracle.”

The third vulnerability relates to the aspirations of ethnic and national minorities. Will the Manchus, the Mongols, the Tibetans, and the Uighur continue to accept domination by the Han ethnic majority if and when they have a chance to imagine a different future? Isn’t China a Soviet-style empire that might, one day, experience the convulsions that its former Communist rival went through in the 1990s?

According to official figures the Chinese hinterland, especially where the ethnic and religious minorities predominate, experienced more than 70,000 “violent incidents”, a euphemism for violent riots, last year. In response, Premier Wen Jiabao proposed agricultural tax cuts and launched a few Potemkin-style “rural development projects.”

“ We cannot develop without freedom,” wrote Li Datong, the sacked editor of “ Freezing Point” supplement.

Without, perhaps, knowing it he was echoing Adam Smith, the first modern economist who showed that while despotic regimes may achieve rapid and impressive growth they can never develop a truly modern and self-sustaining economy.