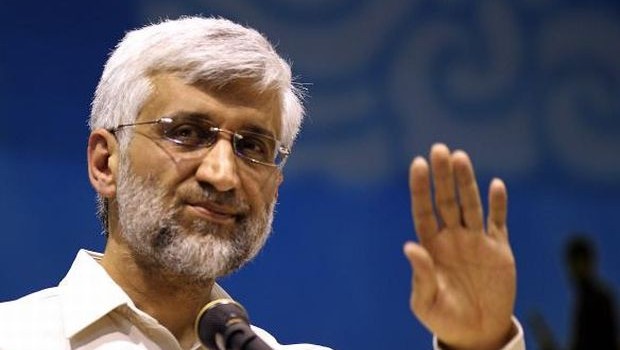

Iranian presidential candidate and lead nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili waves to supporters during a campaign rally in Tehran on May 24, 2013. (AFP Photo)

Saeed Jalili was almost completely unknown in Iranian politics until October 20, 2007, when he was appointed as the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, replacing Ali Larijani, after service as a diplomat in Iran’s foreign ministry. Since then, he has been leading Iran’s nuclear negotiations with the P5+1, the five permanent UN Security Council members and Germany.

He is the youngest of the presidential candidates, and a strong believer in Islamic theocracy, belonging to the radical conservative faction, known as “principalists.”

From war veteran, to scholar, to diplomat

Jalili enlised in the Basij militia during the devastating war with Iraq in the 1980s. He lost his lower right leg during the fighting, and is said to have survived two Iraqi chemical gas attacks.

Jalili was awarded a doctorate in political science for thesis entitled The Paradigm of Political Thought of Islam in the Holy Qu’ran. He also developed his doctoral thesis into a book, The Foreign Policy of the Prophet of Islam. For many years, he taught political science at Tehran’s Imam Sadeq University, an exclusive and prestigious institution that trains the elites of the Islamic Republic.

“He is deeply theologically minded. An education at Imam Sadiq combines a modern education with solid Islamic studies, and its graduates rise to the top posts in Iran,” says Sadeq Zibakalam, professor of political science at Tehran University.

Jalili served for ten years in Iran’s foreign ministry. Colleagues reportedly found him to be a level-headed and unassuming individual, with a modest lifestyle, and one who stayed rigidly within the mainstream of Iran’s revolutionary ideology, something which apparently worked in his favor, given his later career path.

Observers say that his worldview is reflected in his approach to diplomacy, with mixed results. Despite his employment in Iran’s diplomatic service, it is reported that he turned down opportunities to serve abroad, and remains indifferent to the niceties if international diplomacy.

Britain’s former ambassador to Iran, Geoffrey Adams, told US diplomats that Jalili “would lecture on the theological and ideological basis of foreign policy in a very academic but pointless manner,” according to US diplomatic cable from 2007 published by Wikileaks.

According to Nader Entessar, an Iran expert at the University of South Alabama, “the framework from which [Jalili] looks at foreign policy issues is essentially the experience of the seventh century and how it could apply to contemporary events, and I think that is his most important drawback.”

Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment, a Washington-based think tank, believes that Jalili’s experience of the Iraq war had helped to confirm his “revolutionary world view that sees Western nations and culture as anathema to the Islamic Republic.”

A unyielding negotiator

Jalili was an obscure, back-room official until his sudden and surprising appointment as the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council in 2007. Assuming that post automatically made him chief negotiator on nuclear affairs, and involved working closely with Iran’s supreme leader. Some say the post is akin to that of the National Security Adviser in the American political system.

Since then, Jalili has become a symbol of Iran’s resistance to the demands of the West on the nuclear issue, and has been leading the Iranian team in negotiations with the P5+1.

As a war veteran, Jalili’s worldview—particularly his persistent suspicion of the West—was developed during the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq. “He sees the US and Europe as guilty for supporting Iraq against Iran. When he’s sitting down with them, I’m sure his experiences are somewhere in the back of his mind,” Mohammad Marandi, an assistant professor at Tehran University, told Reuters.

“Jalili is a tough negotiator and believes strongly in Iran’s nuclear program and its sovereign rights. He’s not the sort of person to give major concessions,” he said.

Presidential candidacy

Many political figures, especially principalists, have welcomed Saeed Jalili’s registration as a presidential candidate. Jalili has never been actively involved in Iran’s domestic politics, and according to some that could be an advantage for him: the public at large do not have many negative impressions of him, though this could of course change as the campaign continues.

There is some evidence that his hard-line approach to foreign affairs also translates into his views on domestic policy. During a recent presidential debate, Jalili emphasized the difference between the role of women in Western societies and Iran, and said that Iranian women should make home and family the focus of their lives, rather than pursuing careers. He also upheld a strong role for the state in regulating the nation’s cultural and social life, in order to ensure it remains “pure.”

At the beginning of the election season, there was much speculation that two other conservative candidates—Qalibaf and Velayati—would withdraw from the race in favor of him, though this now seems unlikely. One candidate, Kamran Bagheri Lankarani, a former health minister and hardline conservative, withdrew his candidacy in favor of Jalili on May 19th.

Nuclear defiance

Saeed Jalili has pledged not to retreat from Iran’s nuclear rights if he is elected president, making any compromise on the nuclear issue an unlikely prospect if he is elected.

In an interview with London’s Financial Times published on May 16, Jalili said that he would follow a policy of “progress, justice and resistance” as president, and emphasized that the US-engineered unilateral sanctions on the Islamic Republic over its nuclear energy program can be easily “turned into opportunities.”

“My understanding is that the more we rely on our religious and internal principles, the more we can create the capacity to pursue the path of progress and the more we can resist,” he said.

In response to a question about the possibility of direct talks between Iran and the US, Jalili told the Financial Times that “the main problem is that the US is not logical.”

Timeline

• 1965: Born in the northeastern city of Mashhad.

• 1989: Joins Iran’s Foreign Ministry

• 1991–1996: Head of Iran’s Foreign Ministry Inspection Office.

• 1998: Appointed deputy director of the Department for North and Central America at the Foreign Ministry.

• 2001: Appointed as director of policy planning in the Office of the Supreme Leader of Iran.

• 2005: Selected as an advisor by Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

• 2007–present: Secretary of Supreme National Security Council.