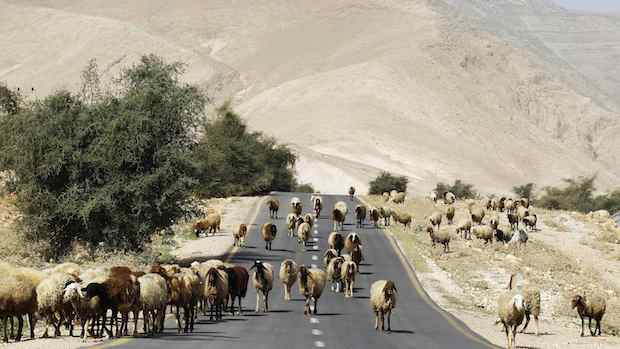

A sheep walk on a road as they graze in Palestinian village of Al-Auja, near the West Bank city of Jericho, on March 7, 2014. (REUTERS/Ammar Awad)

Amman, Reuters—The Middle East’s driest winter in several decades could pose a threat to global food prices, with local crops depleted and farmers’ livelihoods blighted, UN experts and climatologists say.

Varying degrees of drought are hitting almost two thirds of the limited arable land across Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, the Palestinian territories and Iraq.

“Going back to the last 100 years, I don’t think you can get a five-year span that’s been as dry,” said Mohammad Raafi Hossain, a UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) environmental economist.

The dry season has already hurt prospects for the cereal harvest in areas of Syria and to a lesser extent Iraq. Several of the countries under pressure are already significant buyers of grain from international markets.

“When governments that are responsible for importing basic foodstuffs have shortages in production, they will go to outside markets, where the extra demand will no doubt push global food prices higher,” said Nakd Khamis, seed expert and consultant to the FAO.

The Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) shows the region has not had such low rainfall since at least 1970.

This was part of the initial findings of a joint technical study on Drought Risk Management undertaken by several UN agencies, including the FAO, UNDP and UNESCO, that would be formally published later this month, Hossain said.

Water and agriculture authorities, alongside specialist UN agencies, have begun preparing plans to officially declare a state of drought that spreads beyond the Eastern Middle East to Morocco and as far south as Yemen, climatologists and officials say.

Drought is becoming more severe in parts of the Eastern Mediterranean and Iraq, while Syria, having seen several droughts in recent decades, is again being hit hard, said Mohamad Khawlie, a natural resources expert with Planinc, an international consultancy focused on geospatial studies in the Middle East and Africa (MENA) region.

In Jordan, among the 10 countries facing the worst water shortages globally, Hazem Al-Nasser, Minister of Water and Irrigation, told Reuters precipitation levels were the lowest since records began 60 years ago.

Even after an exceptionally heavy snow storm that hit the region in mid-December, the kingdom’s dams are still only 42 percent full, down from 80 percent last year, officials say.

In Lebanon, where climate change has stripped its mountain slopes of the snow needed to recharge groundwater basins, rain is “way below the average”, said Beirut-based ecosystem and livelihoods consultant Fady Asmar, who works with UN agencies.

He said the stress on water resources from prodigal usage was exacerbated by the presence of nearly a million registered refugees since the Syrian civil war began in 2011.

Only Israel will not face acute problems, helped by its long-term investment in desalination plants and pioneering water management techniques.

In Iraq and Syria, where most of the country is too arid for agriculture, civil conflict and lack of water storage facilities will add to the hardship of rural communities dependent on crop cultivation and livestock.

UN-based field studies show that over 30 percent of households in Iraq, Syria and to a lesser extent the Palestinian territories and Jordan, are connected with agriculture.

“Crop production is going down because of drought, and so in these agro-pastoral economies you are looking at many, many lives that are now affected,” Hossain said.

In Iraq, which once boasted the largest tracts of fertile arable land in the region, it is only three years since the last major cycle of drought ended, which covered more than 73 percent of the country.

Extracts from a soon-to-be released UN-commissioned study says drought in Iraq will persist, increasing in severity from 2017 to 2026, increasing further the dependence on foreign food imports by one of the top grains importers in the world.

The UN study extracts say Turkey, where much of Iraq and Syria’s water resources originate, has cut the volume of water flowing into the Euphrates and Tigris rivers by dam construction to meet their own growing domestic needs.

Syria

A poor rain season in Syria has already hit its 2014 wheat outlook in the main rain-fed areas in the north eastern parts of the country, which should be ready for harvest in June and July, Syrian agriculturalists say.

Experts say that even if late heavy rain comes in March, this will not save the rain-fed cereal harvest, which farmers are already resigned to relegating to animal fodder.

“When there is delay in rains, then the cereals will eventually wilt. Annual growth has not been achieved for the rain to come and continue maturity of the stalks,” Asmar said.

Crop production in the conflict-torn country that once boasted bumper wheat seasons is expected to decline further.

Syria’s wheat production is now pinned on the irrigated sown areas that depend on the Euphrates and underground water, which before 2011 accounted for no more than 40 percent of total annual production.

The drought and war could slash Syria’s total wheat output to less than a third of its pre-crisis harvest of around 3.5 million tonnes to just over a million tonnes in 2014.

Agricultural experts say the most favorable estimates for last year’s harvest did not exceed 2 million tonnes.

Drought that peaked in severity during 2008 and 2009 but persisted into 2010 was blamed by some experts in Syria for the soaring food prices that aggravated social tensions and in turn triggered the 2011 uprising against President Bashar Al-Assad.

“Prior to the protests, food costs were soaring. In fact, because of these food costs, the protests were instigated, so this was brought on by drought and lack of planning,” said FAO’s Hossain.

Economic hardship was aggravated by faltering public subsidy schemes that once efficiently distributed subsidized fertilizers and seeds to millions of drought-hit farmers in both Syria and Iraq, agro-economists add.

Middle-Eastern experts predict more frequent drought cycles in coming years, accompanied by delayed winter rainy seasons that damage fruits by promoting premature flowering and prevent cereal crops growing to full maturity.

“The climate change cycles are now shorter, which means . . . we will eventually have less rain and more frequent droughts,” Fady Asmar said.