Istanbul, Asharq Al-Awsat—Founded 350 years ago, the Egyptian market in Istanbul—a hub for trading spices and seasonings between East and West—continues to entice customers. The port city of Istanbul’s geographical proximity to Europe made it a suitable destination for trading wide varieties of spices, many of which originated in India and were exported from Egyptian ports. The market was consequently dubbed the “Egyptian market” by locals.

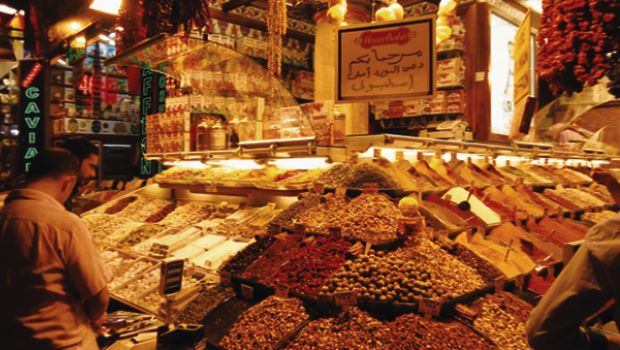

The Arab identity of the market still exists to day, and it is what first grabs your attention upon entering the roofed bazaar. The Arabic language is used frequently, between vendors and customers—Arab and non-Arab alike—many of whom speak in broken Arabic. Nevertheless, Arabic remains the central language of shopkeepers’ cries in the market. Often, they are trying to entice customers by announcing special offers for their products, which fill the market’s streets. The smells of spices and condiments overpower the market’s passageways.

The market was originally built during the reign of Sultan Murad in 1597, with the aim of raising funds for the “New Mosque”—known as Yeni Valide Camii in Turkish—which still stands near the marketplace. Rental income from the market continues to fund the running of the historic mosque.

The market officially opened in 1664, around 70 years after its construction began. Its distinguishing features include its stone walls and floors, as well as its ornate domes and L-shaped design. It is also the second-largest bazaar in Istanbul, consisting of 88 chambers, 21 of which sell gold and copper, 10 sell gifts and luxury goods, four sell clothing, and the remaining 53 sell herbs, spices, nuts, condiments, cheeses, sausages, dried fruits, jams and dried vegetables, which are a specialty of the market.

The market also sells beauty products made from natural ingredients, such as henna, natural sponges, oils and rosewater. Moreover, there are many powders that were traditionally used in Turkish baths as a means of purifying the skin and looking after it.

Vendors interviewed by Asharq Al-Awsat during a tour of the market said that the origins of the market restricted it to the buying and selling of spices and seasonings. Nevertheless, the economic crisis that swept Turkey after the Second World War convinced the government to allow new products such as basic foods. The market was also extended to allow shops to open outdoors, and not just within the traditional roofed market. Many of these outdoor small shops resemble the market’s interior, but they specialize in different products, such as fish and toys.

The vendors boast about the global celebrities who have visited the market. The owner of one stall, a Hazer Baba candy and sweets store, met Queen Rania of Jordan during one of her trips to Turkey. Malatya is not quite the biggest store, but it is undoubtedly the oldest—almost as old as the market—and is strategically located at the market’s entrance, where everyone has to pass it as they come and go. The store specializes in a range of good quality natural sponges, usually sold at high prices. In addition, the store sells a vast collection of spices.

As well as spices, the vendors believe that what distinguishes this market is also the wide variety of Turkish Delight on offer to visitors—and it is on display wheveever you look. Some are made with natural cream, flowers and nuts, quite different to the conventional Turkish Delight sold in the region.

According to the vendors, around 86 percent of spices sold at the market are still imported from India; only around 5 percent are produced in Turkey. The remaining percentages of spices come from various countries, including China and Bangladesh. The shopkeepers also estimate that approximately 100,000 tonnes of spices are sold every year in the market, with sales rising into the millions of dollars.