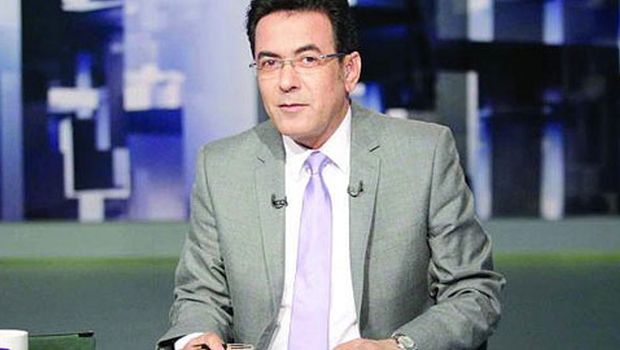

Cairo, Asharq Al-Awsat—Egyptian media personality Khairy Ramadan is perhaps best known as host of CBC TV’s Momken (It Is Possible), but he has also worked as a journalist for a number of well-known Egyptian newspapers, including flagship newspaper Al-Ahram.

Ramadan was at the center of events on January 25, 2011, serving as a host on Egypt’s state television. Ramadan’s media career has fluctuated along with the political situation in post-revolutionary Egypt, from interviewing leading officials to being dismissed as a faloul, a remnant of the former regime. Ramadan talks to Asharq Al-Awsat about Egypt’s post-revolution media—first under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), then under Islamist President Mohamed Mursi, and now in the post-Mursi era.

Ramadan speaks about his secret meetings with the Muslim Brotherhood, the Bassem Youssef crisis, and his future hopes for Egypt’s media.

Asharq Al-Awsat: What is your view of the performance of the Egyptian media following the January 25 revolution?

Khairy Ramadan: After the January 25 revolution, the media was in a state of chaos and confusion; no one knew where things were heading. The Egyptian media became too personal, and those who worked in the media found themselves taking different directions; some said they were pro-revolution and supported the will of the people, others found themselves preoccupied with denying their links to the former regime. In other words, the media at the time was egocentric, and thus it lost the voice of reason. This is one of the reasons why the revolution was derailed and distorted.

Q: What about the media under SCAF?

A considerable amount of political escalation was being practiced by pro-revolution media figures who tried to continue what the media had begun [going after the remnants of the Mubarak regime]. Others tried to flatter SCAF, denouncing critics as traitors to the homeland. As a result of that, two conflicting fronts in the media emerged: one that glorified SCAF, and another that criticized it. This is not to mention the Islamist and Muslim Brotherhood TV channels that were removed from the scene. At the time, Egyptian media was fragmented and disjointed. However, it later united when everybody felt that the homeland was being lost under the Brotherhood’s rule. Everyone began to work together, away from personal or partisan interests, until the Muslim Brotherhood was toppled on June 30, 2013. But the Egyptian media has lately returned to its old habit of exchanging accusations and declaring each other traitors. In fact, the chaos and the state of polarization returned.

Q: Which of these labels apply to you?

At the beginning in January I was in a state of confusion, like everybody else. In my work I always concentrate on the opposing point of view, but in a respectful manner. It was my fate to be working for the official state television channel at the time of the January 25 revolution, a sin that many see as unforgivable. I worked on January 25 and 26, 2011, but later I left. I resumed work after the Battle of the Camel [February 8, 2011, when Mubarak forces riding horses and camels attacked protesters in Tahrir Square] at the request of Ahmed Shafik, the then-prime minister, who wanted me to conduct a televised interview with him. I agreed and my questions to Shafik were neutral, but people dealt with me as I were faloul.

Q: You have famously defended the Muslim Brotherhood on several occasions, including Mohamed Mursi’s own son, Osama. How does that sit with you now?

I did not defend the Brotherhood. Osama Mursi asked to appear on my show in order to clarify the nature of his relationship with [Tunisian Ennahda Movement leader] Rachid Ghannouchi. I did my job and listened to his viewpoint regarding this issue. At the time, I hoped Mursi would succeed and work for Egypt, not the Brotherhood. I even used to be friends with some senior Brotherhood figures, such as Essam Al-Erian.

Q: Did you become friends with them before or after they came to power?

I met [Deputy Muslim Brotherhood General Guide] Khairat El-Shater and Hassan Malek [chairman of Egypt’s Business Development Council under Mursi] in 2005, before they were arrested later that year. We prayed together and I was questioned by security services about whether I belonged to the Brotherhood. I also conducted several interviews with Mohamed Mursi.

Q: Have you held any secret meetings with the Brotherhood?

Yes, I held two secret meetings with Shater for a total of 11 hours at a friend’s house. We met at his request, but I have not spoken about the details of that meeting because this was in confidence and Shater said I was not allowed to do so. He asked my help and said that certain figures working in the media are ignorant. He asked me to work for him at the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP) and the presidency, but I declined.

Q: You own part of Egypt’s well-known CBC TV. Are you involved in editorial decisions there?

Not at all. I deal with the administration just like any other colleague does. I do not interfere in anything relating to the administration of CBC TV. I own 5 percent of the TV channel.

Q: What about Bassem Youssef being taken off the air? Did you get involved with that crisis?

I always interfere in any crisis Bassem Youssef has with CBC due to our good personal relationship. Bassem’s problems with the TV channel are over technical and financial issues, and so the TV channel’s board of directors decided to take his show off the air. Nevertheless, as a media personality, I am against stopping any show and I have issued a statement in solidarity with Bassem Youssef.

This is an abridged version of an interview originally conducted in Arabic.