Beirut, Asharq Al-Awsat—There have been rumors that the doors of Beirut’s Magen Avraham Synagogue are set to reopen after more than 40 years, with Lebanon’s smallest minority moving to reclaim its religious identity and heritage in a country where, since the establishment of the state of Israel and the rise of slogans of resistance, it has become increasingly difficult to be a Jew.

Lebanon’s Jews have become adept at concealing their true heritage, hiding behind fake identities and false religious practices. But many are hoping that, should the Magen Avraham Synagogue in the capital re-open, it would mark a homecoming for the country’s historic Jewish community.

The “Israeli community”

Historically, Lebanon’s Jews were just another tile in the bright mosaic of the country’s diverse ethnic, sectarian and religious mix. However, all this changed on May 14, 1948, following the establishment of the state of Israel and the outbreak of successive Arab–Israeli wars. For the past four decades, Lebanon’s Jews have been living in a state of fear.

While the Lebanese state officially recognizes the existence of Lebanon’s Jewish community, affording it civil and political rights, this has rarely translated into recognition on the ground. Designated the Ta’ifiya Al-Israiliya—the Israeli community—in official statements, the community has found its fate overshadowed by the Zionist state to the south.

The presence of Jews in Lebanon dates back to Ottoman times (1516–1918 CE). During the French Mandate years, the authorities officially recognized the existence of the “Israeli community” on March 13, 1936, with records confirming that this community comprised at least 5,000 members. In this case, the term “Israeli” related to the Hebrew term for Jacob, the third patriarch of the Jewish people, rather than referring to any political Zionist ambitions. But the “Israeli Community” eventually found itself in the crosshairs over this etymological misunderstanding, following the establishment of the Israeli state.

The head of the Jewish community in Lebanon, Isaac Arazi, told Asharq Al-Awsat: “We are experiencing a problem regarding our name because of its sensitivity to a large number of Lebanese, and we understand that.”

He added, “We tried to work with the former minister, Ziyad Baroud, when he headed the Interior Ministry to change the name to the ‘Jewish’ community, but were unable to achieve this. This is something we are working on to this day.”

Identity crisis

Arazi explained that efforts are being made to revive the community’s public presence in Lebanon, including renovating and reopening the Magen Avraham Synagogue—the only existing synagogue in the capital: “Lying in the Wadi Abu Jamil neighborhood of the Beirut Central District, historically home to the largest number of Jews, it was destroyed during the civil war that broke out in the 1970s.”

He told Asharq Al-Awsat: “We have managed to collect donations from the Jewish community abroad, all of them being Lebanese Jews. Christians and Muslims have also contributed to the reconstruction of our synagogue.”

But the perceived relationship between Lebanon’s Jews and the Jewish ‘homeland’ to the south raises major problems for some Lebanese. Speaking forcefully, Arazi said, “To be clear, if our allegiance was to Israel, then we would not stay here another moment.” He explicitly denied any relation to those who wish to live on the land of Palestine, stressing that “not all Jews are Zionists. Our identity is Lebanese and we belong to Lebanon, a hundred percent.”

But Sonia, a Lebanese Jew in her sixties, differed from Arazi. She told Asharq Al-Awsat that, in her opinion, “there is no Zionist or Jewish; Jews are all one and they cannot evade their identity.”

“After the emergence of major hostility between Arabs and Jews, my husband’s family deprived me of my children because of my Jewish heritage,” Sonia continued. “They fought me using all forms of psychological torture. I left my family, who had chosen to go and live in Israel, in order to stay in Lebanon with my husband and children. But the consequences of the Israeli–Arab conflict show no mercy for my existence as a human being.”

Sonia said that she did not care about the isolation imposed on the community, ending her comments unequivocally. “When I die, I want to be buried in a Jewish cemetery with a Jewish rabbi praying over me,” she said. “The Torah is my sacred text, and Judaism is my religion. I will never give that up.”

Hiding in Plain Sight

According to official statistics published in 2003, there were only 60 official members of the so-called Israeli community in Lebanon. More accurate statistics, however, indicate that this number is closer to 1,500, with most members officially switching to other religions in order to avoid persecution. One such clandestine member of Lebanon’s “Israeli community” is Ibrahim, nicknamed the “tailor of the princes.”

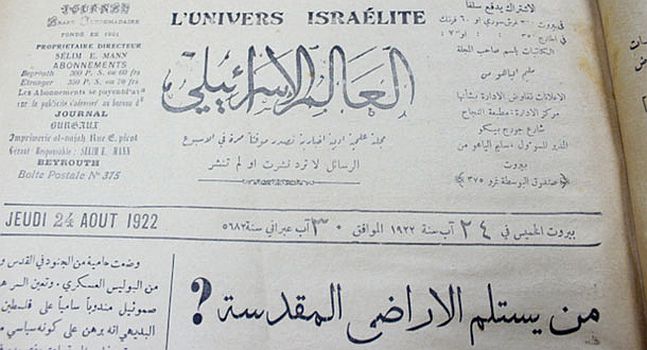

The August 24, 1922, edition of a Lebanese Jewish newspaper called the “Jewish Universe.” (Asharq Al-Awsat)

Qur’anic verses hang of the walls of the shop belonging to Ibrahim, a Jewish tailor in his seventies, along with pictures which dispel any doubts a visitor might have about his identity or religion. He sits on a brown leather chair wearing brown wire-framed glasses. In his hand he holds sewing tools which have accompanied him for more than 25 years—a needle, some thread—and some slacks that need mending.

Speaking with a Syriac accent, Ibrahim welcomes the customers who frequent his shop to buy suits and shirts because of the high quality of his tailoring and his reputation in the neighborhood.

Ibrahim told Asharq Al-Awsat: “On paper, I am a Muslim. I changed my religion to escape the problems and absurdities that surrounded me. Some Lebanese do not accept our presence among them, and we have become obsessed with living as Jews in public.”

He stopped for a moment to light his cigar and brush the dust off his white shirt before continuing his narrative, recalling a time when Lebanon’s Jewish community did not have to hide: “Tailoring is a family business. I used to tailor clothes for princes, ministers and ambassadors of all Arab nationalities. I used to carry a diplomatic passport and receive invitations from Arab notables to accompany them to events in order to take care of their uniforms.”

Ibrahim laughed when asked about the way of life for a Jew in Lebanon. “Jews in Lebanon experience the same difficult social conditions as the rest of Lebanese society, and share with them a common concern for a country on the brink of the abyss,” he said. “Their opportunities for friendship are limited, and they keep their ‘Jewishness’ a secret. I’m one of them.”

Remembrance of things past

On a street opposite Ibrahim’s shop, two women live in a nursing home. The home is old-fashioned, and its walls are decorated with paintings that demonstrate good taste. A clean and uncluttered grand piano sits inside the house with a book of sheet music perched on the side of the bench. Small religious tokens are scattered around, including a menorah.

A woman in her eighties spoke very slowly while sipping coffee with milk, her hands shaking. She relived the memories of her childhood in Wadi Abu Jamil—the former Jewish quarter of Beirut—with great sadness. “I was a music teacher,” she said. “I used to teach students how to read sheet music, and I loved to play the piano. My parents died and I was left alone with my sister in Lebanon after our relatives and friends traveled to the land of exile [Israel], leaving behind their homes and property. They still dream of someday returning to their first and only country: Lebanon.”

Speaking in refined French, she told Asharq Al-Awsat: “The number of Lebanese Jews today does not exceed 200, all of whom are between 50 and 70 years old. And the number of married women among them is few because of the great migration, which emptied the country of its Jewish men. It is difficult for a Jewish woman to be in a relationship with a man from another religion who does not accept the idea of their children, male or female, carrying the religious identity which, according to the Jewish religion, the mother passes on to her children at birth. So we are left without family.”

The “professor,” as she likes to be called, described Lebanon as an “open country” and its people as “intellectuals,” denying being exposed to any insult or abuse because of her religion. Friendship, love, and mutual respect link her with her neighbors. “In the 1970s, many people tried to entice us to travel to Israel with attractive offers, but the idea was rejected outright,” she said.

“Some bigots may ignorantly judge us, but they have to remember before anything that we are human beings.”