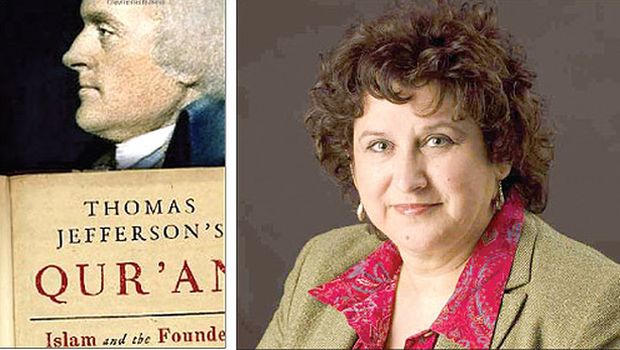

Denise A. Spellberg, author of Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders. (Asharq Al-Awsat)

Washington, Asharq Al-Awsat—Denise A. Spellberg is an American scholar of Islamic history. She is an associate professor of history and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas and holds a PhD from Columbia University. She is also the author of Politics, Gender, and the Islamic Past, which looks at the portrayal of Aisha in Islamic tradition.

Spellberg is perhaps best known in the media for the controversy that surrounded the Sherry Jones novel, The Jewel of Medina. Spellberg sharply criticized the novel from a historical perspective, informing publisher Random House that the book might result in violence by radical Muslims.

In her latest book, she looks at the impact that Islam, in particular a copy of the Qur’an owned by Thomas Jefferson, had on the birth of the US Constitution and the concept of religious freedom during the infancy of the United States of America.

Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders is published by Knopf Publishing Group and was released in October 2013.

Asharq Al-Awsat: How and why did you become interested in Thomas Jefferson and his dealings with Islam?

Denise A. Spellberg: I teach early Islamic history. This project began accidentally, when I found an advertisement for a play, titled Mahomet the Impostor, performed in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1782. It had never occurred to me before that early Americans knew anything about Islam. If they had seen this play, they would have absorbed only a standard European anti-Islamic polemic about the Prophet as an impostor who spread a false religion by the sword.

But this exclusively negative perspective about Islam, then predominant in Europe and America, caused me to wonder: Were Muslims always cast by early Americans as enemies? Were there any exceptions to this dominant view? I began to search.

Two years later, I found evidence to the contrary that intrigued me. In 1788, a delegate to North Carolina’s convention to ratify the US Constitution asserted that without a religious test, Muslims—then termed “Mahometans”—might one day hold elected federal office, even the presidency. (At the time, tests or oaths only Protestants could pass excluded Jews, Catholics, and, implicitly, Muslims, from political office in almost every one of the thirteen states.) A lawyer named James Iredell argued in support of the Constitution—and Muslim rights—in North Carolina. I wondered where he had found such an inclusive idea. I found sources for this inclusive thinking about the religious toleration of Muslims, which I trace in my book back to 16th-century Europe.

Q: How and why did Jefferson become interested in Islam and Muslims?

Jefferson bought a two-volume Qur’an in 1765, 11 years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence. He was a law student at the time, and he would have considered the sacred text a source of law. The founder bought the British George Sale’s “translation,” the first directly from Arabic to English. With his Qur’anic translation, Sale also included a two-hundred-page overview of Islamic history, belief and ritual that was far more accurate than previous accounts.

Around this time Jefferson also took note of a much earlier English legal precedent that refuted the idea that “Turks” [Muslims] were “enemies for life.” Instead, he read the opposite: “Tho’ there be a difference between our Religion and theirs, that does not oblige us to be Enemies to their Persons; they are creatures of God and of the same kind as we are.” These words must have influenced his view of Muslims.

In 1776, a few months after writing the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson wrote down a key phrase from John Locke’s 1689 work on religious toleration: “Neither Pagan nor Mahamedan [Muslim] nor Jew ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the Commonwealth because of his religion.” This line exists in Jefferson’s handwritten notes. The precedent would animate key legislation he wrote in his native state of Virginia that would extend religious liberty and political equality to Muslims.

Q: What were Jefferson’s views of Islam and Muslims?

Jefferson’s early views of Islam were often critical and incorrect. He seems to have absorbed some of these directly from Voltaire, especially his wrong idea that Islam repressed scientific inquiry. Jefferson invoked these precedents in early political arguments to separate religion from government in Virginia.

In contrast, Jefferson’s supported a future in which Muslims might one day be American citizens, at a time when this perspective was not popular. In 1821, five years before his death, and after waging a war against the ruler of Tripoli, he affirmed that he had intended his Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom in Virginia, made law in 1786, to include Muslims explicitly. George Washington and James Madison would have agreed with him.

As a diplomat and a president, Jefferson negotiated with two Muslim ambassadors directly. The first—from Tripoli—he met in London in 1786. The second, from Tunis, the founder entertained in Washington, DC, in 1805, as president. To accommodate this first Muslim ambassador to the US, Jefferson moved the time of a state dinner from mid-afternoon until sunset because of Ramadan.

During this same time, President Jefferson’s letters to the rulers of Tripoli and Tunis suggest that, for the first time, he made use of his knowledge of Islam in diplomacy by invoking the idea of a shared God. Jefferson closed one of his letters to his then-enemy, the ruler of Tripoli, with the benediction that God “may preserve your life, and have you under the safeguard of his holy keeping.” Was this just an attempt to end hostilities, or a true reflection of Jefferson’s understanding of Islam as a monotheistic religion, at a time when the founder’s own beliefs had evolved to embrace Unitarianism, a rejection of the Trinity and the idea of Jesus as divine?

We know for certain only that he never expected these state papers to be read by the American public. We also know that Jefferson wrote these invocations of the deity at a time when the US was not a dominant military power in the world.

Q: How did those with different beliefs from Jefferson view Islam at the time?

Most other early Americans were content to disparage Islam and feared Muslims, especially due to conflict with the Corsairs of Tripoli, Tunis and Algiers. John Adams understood the conflicts with North African powers in religious terms, but Jefferson did not. He defined the issue politically and economically. However, once John Adams left the presidency, he did buy a Qur’an in 1806, the first American printing of an earlier English translation of 1649, one overtly hostile to Islam.

Q: What can you tell us about the actual presence of Muslims in the US at that time?

Jefferson believed that his beloved Bill for Establishing Religion protected Muslims, at least theoretically, but he never knew that the earliest American Muslims were slaves of West African origin, with neither freedom nor rights.

Race and slavery obscured the presence of Islam in America. (Some historians estimate that there were thousands or even tens of thousands of Muslim slaves in North America by the 19th century.) Jefferson never made this connection, presuming that future American Muslim citizens would be white, foreign and free. Some Muslim slaves may even have labored on his plantation, but there is no evidence that he ever met or owned Muslim slaves. In contrast, we know that George Washington, who also supported Muslim religious liberty and rights in theory, actually owned two women [Muslim] slaves, known as “Fatimer,” and “Little Fatimer.”

Q: Can you clarify the seeming contradictions between Jefferson’s ideals regarding liberty and religion, and the fact that he was a slave owner?

Jefferson was a man of his time regarding slavery, never freeing all of his slaves—as Washington did at his death—or even supporting abolition. This is the tragic irony of the limits of his ideals about religious liberty and political equality for Muslims. They were contradicted by his support for slavery that oppressed the first American Muslims.

Q: How did Jefferson deal with the Muslims he encountered, such as the North African corsairs?

Jefferson privately supported a war to end “piracy” as early as 1784—a war he would wage as president against Tripoli in 1801, the country’s first foreign war and the first against an Islamic power. But his diplomacy [and] his treaties suggest that he never saw the conflict as a religious one. Indeed, Jefferson’s treaty with Tripoli in 1806 affirmed: “As the government of the United States of America has in itself no character of enmity against the Laws, Religion, or Tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] . . . no pretext arising from Religious Opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the Harmony existing between the two Nations.”

Q: In your view, how would Jefferson have handled Islam and Muslims following the 9/11 attacks?

As a historian, I have no evidence for what Jefferson’s behavior would be in the 21st century, except what might be assumed from his 18th-century legislation and presidency. From that, I speculate that he would have distinguished between American Muslim citizens with rights that are protected and foreign criminals waging cowardly attacks under the false pretense of religion. Second, I suppose, he would have taken “Islam” out of the equation of a war against “terror” and seen the problem as a purely political one.

Q: In your book, you write that “ultimately, the status of Muslim citizenship in America today cannot be properly appreciated without establishing the historical context of its 18th-century origins.” What precisely do you mean by this?

I wanted to document evidence—and there’s lots of it in my book—that American Muslim citizens and their rights have a history rooted in the most cherished ideals of the American founding era of the 18th century. Ultimately, there is solid evidence that Muslims were included as future American citizens, not in spite of their religion, but because of it.

Q: Finally, while you argue that Muslims were included as future American citizens in your book, the reality on the ground today is that Muslims are viewed with suspicion and doubt, particularly by the Christian Right and the Tea Party. Do you think this is likely to change in the future?

In the 18th century, most Protestant Americans feared not just Muslims, but also Jews and Catholics. It is important to remember that Jews and Catholics fought into the 20th century to claim rights assured them in theory in the US. Both groups were targeted as un- or even anti-American because of their religions. Those who now make American Muslims the objects of hatred and bigotry employ very similar language and tactics that seek, in some cases, to eliminate the political equality of all non-Christians. These attempts are fueled by an organized, well-funded minority of extremists. I believe that they must be fought with historical precedent and legal action. These “nativist” racist hatreds will not prevail, because they are unconstitutional and, ultimately, un-American. A positive sign of this is the election of two American Muslim Congressmen, Keith Ellison and André Carson.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks