A few days ago, I traveled to the so-called Officers Camp in Al-Raihaniya, where, for the first time since the start of the revolution, I met two of the main militant groups. The first group was comprised of former civilians who come from the Mount of the Kurds region—the birthplace of my forefathers—who are currently playing a leading role as one of the formations of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) there. The second group was made up of several soldiers who had defected from the regime’s army but who did not join the FSA. This is the case with the majority of the defectors who, after joining the revolution, were scattered across Turkey, Jordan and Egypt despite the highly significant role played by some of them, whether in the establishment or the leadership of the FSA.

As an entity, the FSA is odd and difficult to understand. You can feel that it is fully formed, but at the same time you feel it does not exist at all. The FSA has its membership, but lacks the organization of a standard army. It does not have the power to force its affiliates to carry out its orders. It lacks cohesion, and so it is no wonder that the FSA is an entity with little organization whose leaders give orders to only part of the forces under their command.

For the FSA, affiliation does not start from the top—from the leadership—and then flow down to individuals. Rather, affiliation depends on the individuals’ readiness to carry out orders, and also on their particular links with their leadership. So it is a blend of a partial, and often fragile, hierarchical leadership and, in many cases, leadership from the lowest levels, who have influence through their obedience or disobedience. Were it not for the fighters’ determination to overthrow the regime, no power would have been able to force them to fight, which is not the case in ordinary armies.

This must lead to a specific result: Those who defected from the regime’s army do not need permission from anyone to join the FSA or any of its numerous units, although having formerly held a high rank in the regime’s army could prevent them from leading certain FSA units. Furthermore, their military education has played a role in their decisions not to cooperate with civilians who formed their own battalions. And former regime soldiers who became leaders in the FSA have played a key role in keeping away high-ranking defectors, fearing that more experienced officers would take over from them, or perhaps displace them entirely.

So former senior-ranking officers from Assad’s army have been prevented from enrolling in the FSA, which has been a real detriment to the opposition forces. Now that the revolution is about to enter a stage that requires a real ability to undertake large-scale planning, systematic organization, and mobilization of scattered troops, it is necessary that those senior officers are allowed back into military work.

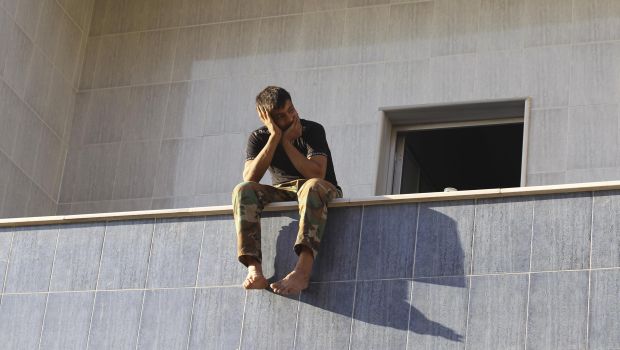

It is unreasonable that 80 percent of Assad’s former officers remain detached from patriotic work, whether military or political. It must be so disheartening for them to discover that they have no place in a battle for which they have sacrificed everything. Those officers did not leave the regime and its army in order to then live in tents and plastic houses, even if they were grateful to whoever offered them, for such living does not befit people from their position; it is not an honorable way to live.

The knowledge and experience of some of those officers can be rivaled only by their peers in sophisticated fighter armies. They have political insights, views and opinions that we Syrians ignore at our own peril. They are not only part of the structure of the military apparatus that of protect the revolution against whomever want to snatch it from the people—its sole rightful owners—they are also politically very knowledgeable, even if they refuse to formally turn into politicians.

Let us set aside minor personal considerations and think only of larger national considerations. Let us start by rectifying the mistakes committed in the military domain, and, if we can, also rectifying our political mistakes. If we could do both of those, our country’s tragedy would end and our people would gain their freedom.