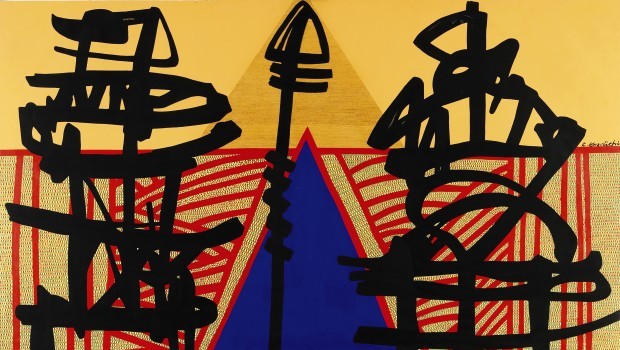

Detail of “Scrutineer of the Hidden Passion” by Rachid Koraichi, one of the 47 works that will be sold at auction by Sotheby’s in Doha today. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Lina Lazaar Jameel, Sotheby’s international contemporary art specialist, said of today’s auction: “Doha is a hugely exciting art hub of the MENA region, and the sale presents exemplary works by extremely important artists.”

In Dubai, where another highly successful Art Dubai fair has just ended, Michael Jeha, managing director of Christie’s in the Middle East, said that their auction proved that “the market responds extremely well to carefully curated sales with great works by artists of high caliber.” He also noted “the increasing interest of international buyers and the maturing of an ever-increasing group of informed and committed local collectors.”

This is fascinating. Not only are international buyers—museums, collectors and investors—swooping like hawks, but there has been a significant increase in the number of buyers from the region. Furthermore, neither group will accept anything but first-class art, of which there is so much, covering such a wide area: not only the Middle East, but also North Africa, Iran and Turkey.

“Al-Moulatham” by Ayman Baalbaki, 2010, acrylic and paper collage on printed fabric. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Only a few decades ago, the Middle East was perceived by the rest of the world as a region that produces extremists, anguish and oil. That image was not helped by 9/11, with all its negative implications. The MENA region was certainly not an area associated with contemporary art, but a Golden Age of creativity was dawning, although of course a vastly rich tradition has always existed. Writing on the theme of “Arabness” after the June war of 1967, when Arab armies were defeated by Israel, poet and critic Buland Al-Haidari described artists as “vying with each other in trying to blaze a new trail which would give concrete expression to the longing for Arab unity, resulting in the Arab world giving birth to an art of its own.”

Venetia Porter, curator of the Middle East department at the British Museum, wrote in Word into Art, the catalogue for a seminal exhibition of contemporary Arabic calligraphy at the museum in 2006, that as a consequence of those turbulent times, “Arab artists, many of whom had been trained in the West, or had been exposed to Western art traditions, began to seek inspiration from aspects of their indigenous culture. The increased use of script by some artists can certainly be seen in the light of this.”

The development of contemporary Iranian art has followed a different path. Lebanese-born Iranian Rose Issa, an independent gallerist and curator of contemporary visual art and film from the Arab world and Iran, points out that “in the last 20 years, the influence of Iranian cinema has encouraged a mix of documentary films and photography mixed with fiction. This has led to a new aesthetic language. Photography came to the forefront in Iran following the Iran–Iraq War, which caused so much loss of human life, [and destruction of] the natural environment and architecture, that artists wanted to document their towns, their families, their history. Photography was the easiest and cheapest way to do this. The strength of Iranian art still comes from the way it tells real-life stories, the poetry of life, winning prizes and influencing Western artists.”

A major exhibition has just ended at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, entitled Light from the Middle East: New Photography. It included the work of several prominent Iranian photographers.

Another continually war-torn area, Lebanon, is also a vibrant art hub despite the fact that there is hardly any government funding for the arts. In other oil-rich countries of the MENA region, as well as in Turkey, the blossoming local cultural development infrastructure is underpinning this Golden Age of Arab art, establishing museums, art fairs, biennales and funding (some) art education. In those countries, the number of private galleries expands each month. Beirut lacks both public and private art venues. Nevertheless, Lebanese artists create powerful, poetic and often very high-tech images, confronting the ghosts of their civil war and seven Israeli invasions.

Pioneering galleries sprang up early on in Cairo from 1982 onwards, and in 2000 the Nitaq Festival began to introduce a new generation of artists and media. Articulate Baboon gallery was founded as “a harborage for counter-culture in Egypt and the Middle East,” according to its creators, and recently showed Palestinian exile Laila Shawa’s Arabopop!

“Secret Garden” by Farhad Moshiri, 2009, oil, acrylic, metal and glitter paint, beads, Swarovski crystals. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

Most contemporary Arab art is iconoclastic, thematically relevant, dealing with the issues of today, and markedly less nihilistic and self-indulgent than most modern Western art. Even in strife-ridden, impoverished areas like Palestine, there is a hunger for art. The situation there is clearly fraught, yet their Riwaq Biennale for Art & Design is a supportive arena for artists—not only to show their work and to dialogue with artists from other countries, but to network with patrons.

Living in London, Laila Shawa cannot return to Palestine. Sotheby’s will auction a piece from her new Gun Series, called Where Souls Dwell III. It is a gold-painted AK45, entirely covered with Swarovski crystals, rhinestones, feathers and butterflies. It is glittery and pretty—but it is a gun. Shawa says: “I come from the most fought-over country in history, and have a particular distaste for the damages and traumas of wars. The butterflies in this work represent the souls of those who were killed by these guns.”

Lurking below the high-rises of Dubai in a few of the only remaining traditional wind-tower buildings are some cutting-edge modern art galleries, most of which operate on an international platform. One of them is Third Line, which has a satellite in Doha. Their stated mission is to show “young, unknown talents and those who live in the West.” Artists of the Arab diaspora, either leaving their countries voluntarily or forced out by politics, almost all retain the spirit of their homeland in their work. Themes of dislocation, identity, loss and alienation prevail, along with inherited memory of an imagined land.

But not all is doom and gloom; there is a sense of optimism that comes from the strength of survival. Moroccan-born Hassan Hajjaj chooses to live partly in Marrakesh and partly in London. His photographic assemblages capture the upbeat rhythm of North African street life with humor, warmth and a degree of kitsch self-mockery. His series of satirical photographs of the young women of Marrakesh, whom he calls the “Kesh Angels,” shows them posed on Harley Davidsons. The heavily made-up eye of one starlet winks at you, the viewer, above her Louis Vuitton-branded djellabah. The veil in the work at the Sotheby’s sale recalls the stars and stripes, and she is surrounded by aluminum tins that look like Coke cans. “I wanted to express so-called ‘Arabic’ work in a cool way,” stresses Hajjaj. He and his contemporaries are playfully questioning stereotypes of tradition and modernity, East and West.

The first contemporary art gallery in the Middle East was set up within Jordan’s National Gallery, kick-started by the collection of Princess Wijdan, who is a respected artist in her own right. She and the National Gallery were instrumental in organizing the first exhibition of Contemporary Art from the Islamic World at London’s Barbican in 1989.

Another space, the Dar Al-Funoon Gallery in Kuwait, was founded in 1994. “It took us ten very difficult years to even awaken interest and awareness for art in the Middle East,” said its owner, Lucie Topalien. “The last few years have gone well thanks to the international auction houses and the media, especially Canvas magazine.” Other magazines, such as BidounM and Contemporary Practices, have also spread the word globally.

The involvement of the auction houses has been crucially important in providing an international platform for Arab artists. Sotheby’s was the first on the scene, with a London auction in 2001; Christie’s opened in Dubai in 2005. Layer came Bonhams and Phillips De Pury. In 2008, Christie’s introduced Turkish art for the first time, and the next year it held a sale of work by Saudi Arabian artists, who began to exhibit at the Venice Biennale in 2009. The Edge of Arabia, a Saudi organization that works to promote Arab and Saudi art, recently opened a London gallery. There were few private galleries in Saudi Arabia until very recently, owing in part to religious objections to depicting the human form. But now they are mushrooming, encouraged by King Abdullah’s strategy to make his state investor-friendly.

Some of today’s artists don’t want to be labeled as “Arab,” “Middle Eastern,” “African” or “Islamic.” They refute the one-dimensional inference of ethnicity, inferring the “Other,” someone non-Western. They are trapped between concepts of “modernity” and “authenticity” when addressing an international audience; when catering to local tastes, they are subject to sensitivity and even censorship about certain subjects such as nudity. Nevertheless, contemporary Arab and Iranian artists, together with their patrons and collectors, galleries and museums, are creating an extraordinarily potent movement, whose ripples are spreading over the globe.

Sotheby’s Contemporary Art Doha Sale takes place at 7 p.m. on April 22 at Katara Cultural Village Foundation, Building 5.