In the case of Algerian artist Houria Niati, this process has been as complex as for anybody else, with many nuanced layers of heritage to reconcile: start with French colonialism, add Arab/Islamic, and mash it up with the Berber blood of her mother. To add to the mix, Niati has been a member of the diaspora since 1977, when she arrived in London. Since then she has built a global reputation, with numerous exhibitions and musical performances. One of the most important North African contemporary artists, she is being recognized with a major exhibition this autumn celebrating 30 years of London shows. The exhibition will showcase work from throughout her career, from oils and pastels to digital installations.

The initial part of a series titled Delirium was given a solo exhibition at London’s Africa Centre in 1984, a first for an Algerian artist. “The roses are incredible fishes. The fishes walk like humans.” These two lines from a poem by Niati were framed and hung at the center of the gallery, indicating her intellectual and visual immersion in the European art movement of Surrealism, in which unexpected elements collide or glide together. Outlines of human figures and faces like masks, human and animal—or mixtures of both—float over dream landscapes, recalling another European artist, Marc Chagall. As one reviewer put it: “There is no perspective, only the warm, giddy sense of a brightly-lit frescoes cave.” Incidentally, Niati acknowledges the influence of the Tassili cave paintings on Algeria’s Saharan fringe.

Niati’s father was an amateur landscape painter, whose style differed radically from her own. “I like Surrealism, I admire the irrational, artists like Dali, Klee and Miro, and I used to argue with my father, saying: ‘Daddy, why don’t you invent something?’” Nevertheless, from an early age she was given paintbrushes, and home was crammed with art books and paintings. “I grew up with the idea that I am an artist,” she told Asharq Al-Awsat.

From early childhood Niati listened to her grandmother’s Arab and Berber tales of myths and oral history. “We have a colorful verbal language, with lots of legends, whose imagery is very surreal. For instance, this culture has no direct interpretation in poetry about women. Instead, the language is metaphorical, using association of ideas.”

All very idyllic, but there is a darker side to her fantasy imagery, the bright colors and light, airy forms of her early work. It is the legacy of the all-pervasive French occupation of Algeria—“We were brainwashed [that] we were French,” she says. Then came the brutal seven-year war for independence. “I knew what death was from six years old. I saw people being killed every day,” she said.

Every night until she was thirteen, the family would huddle in a corner, trying to snatch some sleep, while windows shattered and bombs wrecked their town. At twelve years old, she was arrested for writing graffiti hostile to France, and for joining a demonstration. She was beaten and shoved into a cell, where she was repulsed by the excrement on the floor, and terrified of torture. Because she attended a French school, she was not tortured, but the French head teacher beat her after her release and return to school.

The death of her father when she was sixteen also had a profound impact, including financially, on the large family of eight children. Niati was forced to give up her dream of going to art school for the time being. However, alongside her work at a government ministry she was involved in community theater and art projects, useful experience for her later musical performances.

“But visual art at that time was everything for me,” she tells Asharq Al-Awsat. So, in 1977, she decided to come to England and studied at the Camden and Croydon colleges of art for four years. “I had a lot of help in defining my style and gaining technical confidence. But I kept hearing this word ‘ethnic.’ There was no chance just to be an ‘artist.’”

She tackled this stereotyping, perhaps ironically, in L’oiseau rare de l’anthroplogie, or The rare bird of anthropology. In fact, her work transcends labels and is characterized by a restless dynamism. Hot oranges, throbbing reds, and cobalt blues are sweepingly, thickly applied, or dragged and scratched like painful skin grazes. “Most of the themes I present are about displacement, multicultural backgrounds, the effect of wars, post-Orientalism and the conditions of women,” she said.

Niati is best known for two series of paintings and installations: No to Torture, first developed in 1982–1983, and To Bring Water From The Fountain Has Nothing Romantic About It, created in 1991. A highly potent installation of five paintings, No to Torture is based on the early Orientalist painter Eugene Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, and perhaps it is no accident that it was painted in 1834, two years after French colonial rule was established in Algeria. Picasso painted fifteen canvases inspired by Delacroix’s work, but unlike his abstract versions, Niati’s response to Women of Algiers unites form and content, bringing history full circle, back to the unfortunate lot of many women in independent Algeria that persists to this day. All the trappings of Orientalist enchantment with ‘exotic’ decoration and dress, which endowed those Women of Algiers with some dignity, have been banished from Niati’s interpretation. Now the literally naked truth of their continuing exploitation emerges.

In No to Torture she imprisons, mutilates, and disfigures the women of Delacroix’s brush, relating their suffering to those of colonialism, and indeed the violence, including social inequality, meted out to Algerian women today. Niati also rejects Orientalist evocations of Arab women as sensuous, secluded objects. This romanticized cliché was perpetuated in French colonial postcards, which Niati has digitally manipulated in later work.

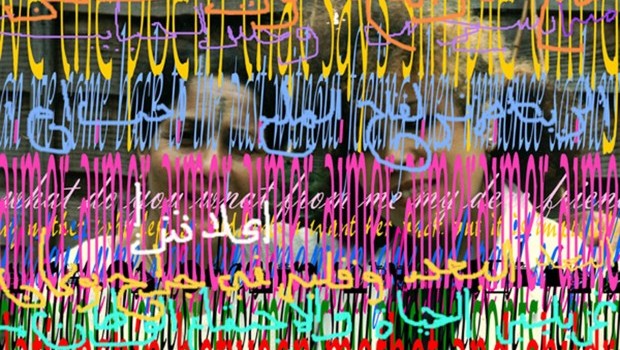

Her work is often self-referential: her 2006 series The Curtains Of Words was based on her childhood and family photographs, the latter taken by her on return visits to Algeria. The ‘curtains’ are words from her poems digitally superimposed onto the photos, silent commentaries on the changes that have occurred in her country. The words are expressed in three languages—Arabic, French and English. “In school I was taught that my ancestors were Gauls, and at home the door was wide open to French culture. But I was brought up in a Muslim family, where customs were strongly maintained,” she told Asharq Al-Awsat

Her Arab/Berber roots are honored, too: “Algerian independence arrived in 1962. I was thirteen at the time and from that moment many questions came to my mind. What did the French give me? What did being Arab or Muslim mean? Who were the Berbers? And so forth. . . . Algeria too has serious difficulties in defining a clear identity for itself,” she added.

Several more series emerged, centered on the search for identity on the part of the artist and the nation. Haunted—Self portrait with a difference was followed by Out of the Ashes, a multimedia installation of painting and digitally carved wooden plates.

[inset_left]A recently widowed friend told me that Houria Niati’s singing had enabled her to weep for the first time since her husband’s death.[/inset_left]

In recent years, Niati has been returning to Algeria for extended periods, researching the role of adornment in women’s lives. A series of digital images titled What If? emerged in 2012 exploring the “value, power and function of personal finery. Women who felt trapped and forced to fight for their family’s survival, who took part in the war of liberation, are still the vehicles for protecting and transmitting their culture. They use stunning jewelry and accessories to proclaim their freedom, their unique identity, but also their sensuality and beauty.”

She added, “It’s their way of ‘being’, existing as individual entities. The question is: will adornment play the same role for future generations? Will female finery ever again be as necessary as it was during colonialism?”

“My interest in personal adornment started when I was very little, during the colonial era, when my relatives from the south came to visit us. I used to stare in fascination at my Berber and Bedouin aunts who helped each other at night to take off the silver jewelry they had been collecting since they were very young, and put it on again in the morning. Their hands were decorated with henna, their eyes made-up with kohl, and they used strong perfume. Enormous turbans draped with more jewelry covered their plaited hair. My Mum normally wore Western clothes, but to celebrate any ceremonies, she would wear traditional costume in the northern Algerian manner, with less adornment. My father, although Arab, always dressed in Western style, since French culture was accepted, even embraced, by urban families like mine; French culture had a huge impact in the north, but they couldn’t curb indigenous rural traditions.”

The What If? series began when a French–Algerian student named Nabila interviewed Niati, who photographed her, and from this encounter emerged a short video and portraits of Nabila, with which she digitally fused a series of images of old photographs of Algerian women in traditional costume. “I found the results astonishing and quite disturbing.”

The openings of Niati’s exhibitions are often emotionally charged events of live musical performance. A Spanish guitarist, Miguel Moreno, usually accompanies her powerful, haunting voice. She was trained to sing Arab-Andalusian songs from a ninth-century repertoire generated in Cordoba by a composer and master of the oud named Ziriab ibn Nafi, with whom she feels a deep connection. Her presence and unique music make these performances moving occasions. A recently widowed friend told me that Houria Niati’s singing had enabled her to weep for the first time since her husband’s death.

“Houria Niati: Identity Search” will be held at Conway Hall, London, from September 21 to October 13.