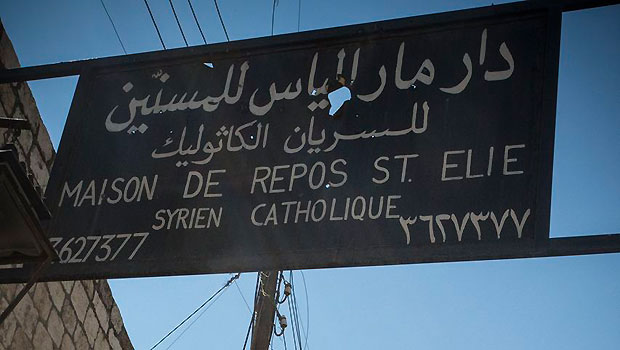

A view of the sign outside the St Elie Rest Home in Aleppo’s Old City. (Asharq Al-Awsat/Hannah Lucinda Smith)

Aleppo, Asharq Al-Awsat—Aleppo’s Old City is a lonely place to walk through these days. The UNESCO World Heritage Site was once packed with tourists who mingled with the locals and bought trinkets in the souk, but today it is deserted except for men in fatigues and stray cats. The only trinkets left are the bullet casings on the pavements. The entrances are sealed by rebel checkpoints, and the ancient, narrow streets inside the citadel have become part of a vicious front line. Walking like schoolchildren in a crocodile line behind a group of Free Syrian Army (FSA) fighters and their commander, we cling to the stonework, first to the left hand side and then to the right, as we try to keep out of the snipers’ sightlines.

Mahmoud Afesh, the commander of the Free Syria Brigade in the Old City, says that his men are walking a tightrope in this famous old district of Aleppo, battling to protect history while holding back an enemy who is armed with heavy weaponry. “We are trying to keep this front line stable,” he says. In recent weeks, he has met with archaeological specialists from Europe to discuss how the citadel can be preserved in the midst of a civil war, as well as how it could be rebuilt once the fighting is finally over. “We are Syrians and we care about our country,” he says. But the Old City must bear a tragedy that is physical as well as human. Most of its residents have left; its irreplaceable fabric is being blasted apart, piece by piece. “I cried when I saw how the minaret of the Ummayad Mosque has been destroyed,” one Aleppine tells me. “They have no respect for history. They have no respect for anything.”

But behind the high, blank walls, through an entrance just yards away from the sniper alley we came down, one group of civilians remains—the most vulnerable and blameless in this war. Forty elderly people used to live at the St Elie Rest Home, run by a group of Syrian Catholics in the heart of the Old City. Now, just eight of them remain: the oldest, the frailest, and the ones who have nowhere else to go.

“Some of the people we looked after here left with their relatives; they went abroad,” says Joana, one of the three carers who have stayed at the home even though the fighting continues to rage around them and everyone else left in the Citadel. “Some have moved to safer areas of Aleppo. But some of the people who live here are just too old and too ill to be moved.”

They face an impossible choice: too weak to run the gauntlet outside to escape the Old City, but also too weak to stay. People have died here during the battles, not from stray bullets or shrapnel but from heart attacks brought on by the terror and the chaos. A flower bed in the courtyard has been turned into an unmarked grave because the Red Cross refused to come and pick up the body of one of the people who passed away. “They said it was impossible for them to come to us—too dangerous,” says Joana.

Yet the home, with its cool courtyard and Catholic iconography, still feels like a sanctuary even though there is a hole in the roof of the tiny chapel where a shell punched through it. Joana says that they rely on the rebels now, that the Sunni Muslim fighters protect them and bring them food and supplies in a daily routine that proves that tolerant, multicultural Syria is still alive. “We Christians are realizing now that this war is not about religion,” says Joana. She tells me that this house was built with money raised through charity and that it symbolizes the true Syria—not a sectarian bloodbath, but a place where people of different faiths have lived peacefully alongside each other for centuries. “The battle here is between the Syrians who care for each other and a dictator who will not step down,” she says.

Like the Old City itself, the bricks and mortar of St Elie is under threat, as are the fragile lives of the people within it. Mahmoud Afesh says that his brigade tries not to use heavy weapons near the home, but the shells still land terrifyingly close. It seems like madness to stay, yet Joana says that she will do so even if all of the people she cares for eventually leave. “This house is two hundred years old and I would stay here just to protect it and all the things in it,” she says. “Because we were here before Bashar Al-Assad, and we will still be here after him.”