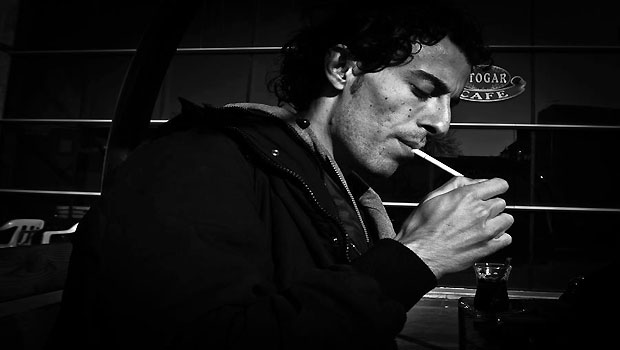

A picture of Syrian revolutionary and former detainee Muhammed. (AAA)

Aleppo, Asharq Al-Awsat—“There are still so many things I don’t understand,” says Muhammed. “Why did I go there? How did I get out?” Lighting another cigarette he pauses to collect his thoughts before resuming his litany of questions. He knows he should have died in a prison cell but did not and is still struggling to make sense of why.

As the Free Syrian Army (FSA) stormed the city of Al-Raqqa earlier this month Muhammed heard it all—the shelling, the fire-fights, and ultimately the retreat of the regime—from his cell in a military prison. For five days he was locked in a room with nine other prisoners as the battle raged around them. They survived on a piece of bread each and two bottles of water between them.

“I spent the time thinking how I was going to die,” he remembers. “Thinking will the FSA shell the building, or will it be bombed by a jet, or will the officers in here kill us finally?”

It was the moment when Muhammed thought his luck had run out. He had already been arrested by the regime on three separate occasions, but each time had been inexplicably released. But now his name was on the wanted lists in Damascus, Deir Ezzor and Aleppo while his laptop was full of pictures of FSA leaders and footage of opposition protests. And in his pocket were identification papers issued by the Islamic opposition front, Jabhat al Nusra.

“When the regime soldier caught me it was just shock,” he says, “because I knew that they would kill me. When they knew what I had, they would kill me.”

His journey to that prison cell began five months earlier, in Aleppo, where he was working as a media activist for the opposition. He was filming a demonstration when the regime started shelling the area, killing twenty-two people and leaving shrapnel buried deep in his left arm. It stayed there for three months until he found a way out to Jordan, where a surgeon removed it and advised him to leave Syria for good.

Helped by a friend in Lebanon he got his name onto a list of injured Syrians who were to be evacuated to Paris. So, knowing that he would soon be leaving, Muhammed decided to travel to Al-Raqqa to say goodbye to his family. “They didn’t even know that I’d been injured,” he says.

To get into the regime controlled city he was told that he must travel on the back of a motorbike, and then walk down a railway track and jump over a wall to bypass a government checkpoint. It was a safe route used regularly by the FSA, but this time it failed. Just after he had jumped over the wall, he saw a regime soldier.

“The soldier said ‘Stop, who are you?’ And I couldn’t answer. It’s crazy, because I’m the kind of person who always makes a plan. If I go to the shop to buy cigarettes then I have a plan. But I simply went to Al-Raqqa and got caught.”

The checkpoint soldiers took Muhammed to a regime base, taking his jacket and shoes from him on the way. There he was taken to the interview room.

“First I met someone called Abu Youssef,” he says. “He’s an officer, a clever one. He spoke with me, just spoke for thirty minutes about right and wrong. ‘You’re wrong, the revolution is wrong. You help America and Israel and you destroy the country.’ And I said, ‘You’re right and we’re wrong but we don’t understand things like you.’” adding “It’s the way to speak with someone like him.”

After the interview; the prison cell. Muhammed still didn’t know where he was so he asked the other prisoners. When they told him that he was being held by the military intelligence, he says he felt nothing. “I knew that they would kill me; it’s impossible to get out. So it’s OK, no problem.” He stayed in the cell for two days.

And then, after the prison cell, the beatings that Muhammed had known would happen from the moment he was stopped in the darkness outside Al-Raqqa. By now Abu Youssef had checked his laptop and spoken with the mukhabarat (intelligence) in other parts of Syria, and he knew how deeply involved he was in the revolution. For three days Muhammed was beaten with electric cables. When he asked his assailants not to hit him where he was still recovering from surgery they gave him electric shocks there instead.

Four days later he was sent back to Abu Youssef. He asked him questions–“silly questions, stupid questions, clever questions”–that spanned the whole of Muhammed’s twenty-four years. The questioning continued for four hours and then the beatings started again.

“I was dreaming of dying so that everything would be OK, and then after three and a half hours I passed out,” he says. “When they came to take me out of my cell again the next day I came out shaking because I was so afraid.”

The beatings and the questioning continued for another two days in a pattern that Muhammed had accepted would continue until he died. But suddenly everything changed. He started to hear voices, and gunfire, and shells falling outside the prison.

“A new prisoner came in and we asked him what was happening. He said that the FSA attacked the regime checkpoints and now they controlled them all. When the battle started the next day the prison officer opened the door, gave us the water and the bread, and that was the last time we saw anyone for five days.”

Trapped in the prison Muhammed and his cellmates could only try to hear the sounds of the battle and guess what was happening outside. They didn’t know that 7,000 FSA troops had surrounded the town and that the government forces were running out of ammunition, until they heard an officer call the head of the government military forces in Deir Ezzor, 200 km to the east. In the first indication that the regime was losing the town, the officer asked if they could use the prisoners to negotiate a safe exit from Al-Raqqa.

“And then Abu Youssef came to us with a good face,” says Muhammed. “He said ‘Hi, how are you? We are very sorry that we didn’t see you in the past five days and that we didn’t bring you any food and water.’” The officer told the prisoners that he wanted to surrender them to the FSA, and asked who had connections with its leaders. “Before we were all claiming that we didn’t know them but now everyone was saying ‘yeah we know, give us our telephones.’”

A prisoner managed to contact a rebel leader, and for five hours the regime and the FSA negotiated. “It was life or death because if the FSA had said no they would have killed us,” says Muhammed.

But then the officers disappeared, closing the door behind them. The FSA had reached the prison and with no choices left they fled. “We heard the FSA coming into the building shouting ‘Allahu Akhbar’, and outside the building gunfire and clashes. And then we knew that we were free.”

Barefooted and with celebratory gunfire exploding around him Muhammed started to run to his parents’ home, through a city he could never have imagined before his incarceration.

“I thought it was impossible for this space, where I was, to fall because the military is like a god. There were rooms full of artillery in that prison. There were MiGs flying over Al-Raqqa. But as soon as I got out I changed my ideas because it was clear that there was no regime left.”

He knows he was lucky to escape but struggles to draw comfort from this. Speaking today from Turkey Muhammed says he does not know what he will do next. He has lost his footage and camera, and says he has also lost his belief in the revolution. The military opposition is fracturing and the political opposition can’t seem to do anything to help the people who are dying inside the country and in the refugee camps outside.

“The Syrian National Council sits in hotels and restaurants in Istanbul, so why would they want the revolution to end?” he asks.

“Most of the FSA fighters are in the streets, not on the front-lines or helping the people. They should fight the regime in a smart way, not stay in the streets and let the regime shell them. This revolution was complicated before, but now I know that it’s even more complicated.”