With everybody preoccupied with attempts to understand the dimensions of the Syrian conflict, it might be useful for those monitoring the situation there to view it from the Lebanese perspective.

It is true that the Lebanese political arena is like a dark labyrinth teeming with intrigue, innuendo, and a surfeit of hypocrisy, because there is no joint national program that transcends sectarian considerations. This is not to mention the fact that due to the regional and international situation, the political scene in Lebanon finds itself turned on its head every now and then, with the country being transformed into an arena for regional conflicts, reflecting the contradictions of the clashing factions.

Following the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war, the Syrian regime succeeded—where others failed—in “managing” the Lebanese contradictions, and persuading a large segment of the Lebanese public that they did not deserve to live in an independent country, and that they were incapable of development a culture of “citizenship.”

Damascus—under the Assad family— took advantage of the Lebanese lack of interest in the importance of citizenship as a necessary step for independence and sovereignty, not to mention small belief in independence as a guarantor for the survival of citizenship. Under Hafez Al-Assad, Damascus cunningly managed to pursue a dual-purpose policy, shifting its aims and attitudes whenever and wherever there was a need for such shifts.

In a shrewd and discerning manner, Assad Sr. was able to contain Iran’s rushed efforts to implement its regional project. Thus, by synchronizing his efforts with the mullahs of Iran, Hafez Al-Assad was able to avoid arousing the anxiety of the Lebanese and Syrian people, whom he was keen to reassure, or should we say anesthetize.

The situation changed, however, with the arrival of Bashar Al-Assad to power.

When the “Lebanese file” was taken out of the hands of the calm and experienced senior advisors of Hafez Al-Assad and placed in the hands of Bashar and his new team, the situation changed completely, at least on the Lebanese front. Following this development, former taboos began to be broken, as did the Syrian regime’s “special ties” with a wide spectrum of Lebanese leaders. In fact, leaders in Lebanon had to adapt to Damascus’s new strategy which was based on a sense of superiority, in addition to a policy of a“stick but no carrot” policy.

There is no need to over-analyze what happened to Lebanon and the Lebanese during Bashar Al-Assad’s early years in power. It is enough to recall February 14, 2005: the fateful day when Prime Minister Rafiq Al-Hariri, along with several guards and civilians, was killed in a car bombing. On that day, fingers were immediately pointed at Syrian and Iranian security apparatus. In a preemptive step, Damascus and its allies constructed the “Takfirist scenario” by promoting the fiction of radical Islamist “Abu Adas.”

At this point, it is worth recalling the rumors that were promoted by Damascus and its security apparatus against the background of their claims that Hariri had supposed links to radical Sunni groups, and that he supported Takfirist organizations. In this case, why would a Takfirist like Abu Adas assassinate one of his sponsors?

In addition to this preposterous plot, only months before the Syrian uprising erupted, senior government figures in Iraq accused the Damascus regime of facilitating the arrival of Takfirist groups into Iraq across Syrian territory.

Furthermore, a certain Syrian radical Takfirist preacher—who settled in northern Lebanon following a considerably long residence in the UK—was arrested in autumn 2010 after being convicted in absentia of belonging to an armed organization, inciting murder, and insulting the government. In late November 2010, this controversial preacher was released from prison thanks to the efforts of his lawyer Nawwar Al-Sahili, a Hezbollah MP who defended him after receiving explicit permission to do so from Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah.

In 2007, Nasrallah himself was among the first to come out to say that attacking the Takfirist Fatah Al-Islam group in the Nahr Al-Bared camp—in northern Lebanon—represented a “red line”. However, when the Syrian uprising erupted, Nasrallah justified sending Hezbollah militants to fight alongside the Assad army against Takfirists!

The presence of so-called Takfirists in Syria has provided the Western powers with a pretext to justify granting Assad tacit permission to crush the Syrian uprising. But even the West, particularly the US, are well aware precisely how and when these Takfirists came to Syria. Most likely, security services in the West monitored and continue to monitor this contradictory/complementary relationship between the Takfirist groups and their breeding grounds, which at first glance seem to be completely at odds with them.

Still, today we hear political analysts and academics trying to pin down the reasons behind Washington’s unwillingness to confront the Assad regime and its backers.

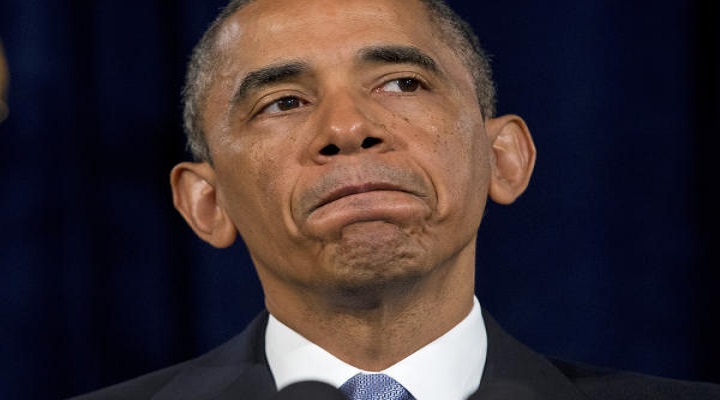

Some are of the opinion that Washington is concerned that “lethal” weapons and military aid could reach Takfirist groups on the ground. Others think that the problem lies with US President Barack Obama himself, whom they describe as being “hesitant” and overly-cautious. A third faction refer to the fact that the US is “exhausted from wars abroad” and that Obama and his administration are keen to respect the desire of the US public not to get embroiled in another foreign military adventure, as shown in opinion polls. While another group claims that the Middle East is no longer a major concern for the US.

A fifth viewpoint, which is both naïve and deliberately misinformed, dismisses claims of US “collusion” in the crushing of the Syrian uprising, attributing the current US stance to a lack of vision on the part of the Obama administration.

The New York Times reported earlier this week that Tel-Aviv is concerned about US leaks regarding Israeli strikes on military targets inside Syria. This prompts one to believe that Tel Aviv and Washington are taking different views of the situation in Syria, dismissing claims of US “collusion”.

However, it is difficult to believe that the US and Israel could take such different views on this issue, particularly to those who are aware of the central place that Israel occupies in US policy in the Middle East. This is particularly the case when we are talking about a regime that has ruled one of Israel’s closest neighbors for over four decades.