For a decade, the United Nations has been studying and debating a phenomenon that has forced itself into political life in numerous countries. That phenomenon is terrorism.

Because of the old adage that one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, efforts to reach consensus on a definition of terrorism have failed. But do we really need a definition? Everyone, especially victims, knows what terrorism does, without needing to define it.

Scholars who have studied the phenomenon also know another thing: terrorism never succeeds in achieving its objectives. It is a false solution to real problems. Terrorists are capable of seizing hostages, planting bombs, murdering individuals and carrying out suicide attacks that claim numerous lives. But they are seldom able to translate those acts into political gains.

In ancient Rome, the assassination of Caesar by his erstwhile friends in the name of saving the republic led to an imperial system under Octavius, the murdered dictator’s adoptive son. In Islamic history, the Hashasheen (Assassins) terrorized people for decades, but they never achieved political power beyond their mountain redoubt in Aalamut, northwest of Tehran.

Europe in the 19th century was the scene of numerous terrorist operations by Anarchist, Nihilist, and Narodnik groups that reaped no benefits from their violence.

In more recent times, terrorist movements have failed in a range of countries across the globe, from Malaya (now Malaysia) to Mexico. For decades, Latin America was the hub of terrorist organizations. The disease did not spare even peaceful Uruguay. Thanks to drug production and export, in Colombia and Peru terrorism became big business. But it did not lead to political power for terrorists.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Western European nations were struck by terrorism. But even though terrorism enjoyed tacit support from segments of the bourgeoisie, it ended in total failure. Decades of violence by the IRA did not lead to the Irish unification.

Over the past three decades, Muslim nations have been the principal victims of terrorism.

In the 1960s and 1970s, terrorism by a dozen different groups hit Iran. But when the Shah fell, none of them achieved power. While exporting terrorism to other countries, the new Khomeinist regime made a point of uprooting the terror groups that had fought the Shah.

Trained by “experts” from Cuba and North Korea, modern Islamist terrorists have not adopted the Hashasheen’s tactics. Instead, they have gone for car bombs, booby-traps and explosives planted in crowded places. The Hashasheen liked to face their victims one-on-one; they would regard their self-styled successors as cowards.

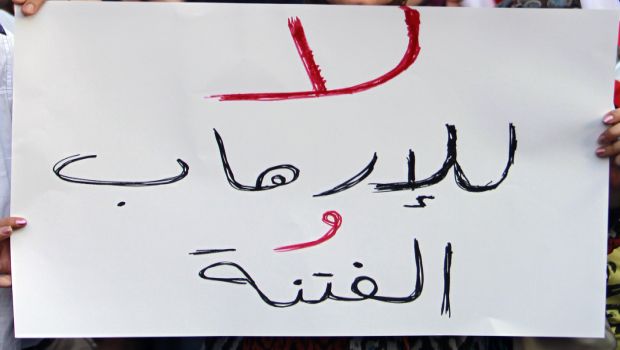

All that brings us to Egypt, which appears to be facing a return to the terrorism campaign of the 1980–2000 period.

That campaign slowed down Egypt’s economic development, disrupted the lives of the people and claimed thousands of lives, but achieved nothing for terrorists. The terror strengthened the authoritarian aspects of President Hosni Mubarak’s rule. Without the 20-year-long terrorist campaign, the Mubarak regime might have morphed into a more or less democratic one, repeating South Korea’s transition from military rule to pluralism.

Today, a new terrorist campaign could bestow a measure of legitimacy on the military-security model of the Arab state that was challenged by the Arab Spring. That model cannot be restored and Egypt cannot sustain another 30 years of clampdown. However, terrorism could be used as justification for prolonging the emergency. Repression breeds terrorism and terrorism generates repression—a vicious circle.

The story of Egypt as it buries its experience with electoral democracy is one of failure across the board. The Muslim Brotherhood wasted the historic chance given it by the electorate. The “democratic” groups, recently symbolized by the Tamarod (Rebellion) movement, have fallen victim to their anachronistic romanticism, ending up with failure. Two years after Mubarak’s fall, the biggest party in Egypt remains the silent majority.

I was never impressed by crowds in either Tahrir Square or in front of the Rabaa Al-Adawiya Mosque in Cairo. Crowds look impressive on television but, in political terms, remain an abstraction. Ultimately, they produce much heat but little light.

We still don’t know what the Egyptian silent majority wants. Revolutions fail when they prove unable to broaden their base to include a chunk of the silent majority.

In power, the Muslim Brotherhood did the opposite with a program that narrowed, rather than broadened, its support base. For all that, those who talk of banning the movement could be making an even bigger mistake. To emerge out of impasse, Egypt needs inclusion—not exclusion.

Terrorism is no answer. But neither is repression.

Much to the chagrin of my Egyptian friends, I never regarded what happened in Egypt as a revolution. I described what happened with Mubarak’s fall not as “regime change” but as “change within the regime.” However, even if we flatter Egyptians by speaking of their “revolution,” Egypt’s experience is not unique. In Europe, too, the revolutions of 1948–1949 were quickly defeated, leading to new authoritarian regimes, notably in France and Prussia.

In Egypt, the only verdict possible is one of failure across the board. Egyptian leaders on all sides would do well to admit that if they are to shape a credible agenda for the future.

A very interesting assessment of the failures of the MB combine and the romanticism of the” ineffectuals.” As a matter of fact, mob rule is an invitation to disaster. Those dreaming” ineffectuals “and mid-night walkers who engineered the uprising of 25 January 2011 were simply unaware of the consequences of their plotting. The fall of Mubarak was not the fall of a benign ruler but also the security and the stability of the state. The inclusiveness which the distinguished columnist is proposing should not exclude all the positive features of the Mubarak era, if it has to accommodate the remnants of the dishevelled MB combine. It is true that Egypt has experienced one failure after another during the past thirty months but a new era is knocking on its doors which may open the gates of transparent democracy, provided all the components of the Egyptian society are assigned their respective roles in piloting the ship of the state.