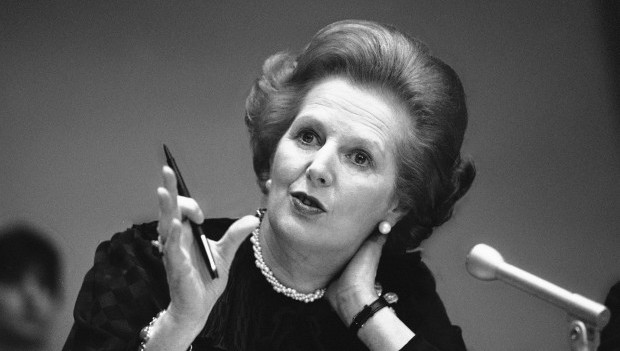

“A voice in the desert!” was the phrase that came to mind after I interviewed Margaret Thatcher in Tehran in April 1978. The new leader of the British Conservative Party was visiting as part of a foreign policy exploratory tour that included Washington, Paris and Bonn.

The interview got off to a dicey start because of a brief elevator failure at the Hilton Hotel where the future “Iron Lady” was staying.

What caught my attention was not the tone but the substance of Mrs. Thatcher’s discourse. She had adopted a vocabulary made up of words and phrases long bequeathed to the dust by common consent. She talked of free enterprise, the market economy, individual responsibility and a strong currency. On international affairs she sounded like Radio Free Europe, the propaganda arm of the CIA in the heyday of the Cold War. In 1978, even the US, thanks to Henry Kissinger’s doctrine of engagement, was far from waging ideological war against Communism: it was subsidizing the Soviet empire with cheap loans and handouts.

Thatcher spoke of “defeating Communism,” which, it was clear, she also took to include other forms of collectivism such as socialism in Western Europe.

In the preceding years, I had interviewed several British leaders either in Tehran or in London. They included prime ministers Edward Heath and James Callaghan—not to mention Defense Secretary Lord Carrington and a string of foreign secretaries from Sir Alec Douglas Home to Dick Crossland, Michael Stewart and David Owen. Although from parties opposed to each other, on key issues of domestic and foreign policy, all had sung from the same hymn sheet.

They were consensus politicians with a managerial, rather than ideological, view of the role of the government.

I had been impressed by Callaghan’s emphasis on patience as a high virtue for politicians in a democracy.

One of his phrases still rings in my ear: “Though it might take a society to the edge of un-governability, democracy remains the most efficient form of government.”

At that time, of course, Britain was on the edge of un-governability, with endless strikes and a plummeting currency.

Heath had won my sympathy because, he had fallen asleep for about 15 seconds during the interview—proving that he was human after all.

For both Heath and Callaghan, the subtext was that the government was a problem-solving machine. Now, here was Thatcher pretending that government itself could become a problem.

The woman really looked like a bolt of the blue, an impression emphasized by the blue dress she was wearing. Here was a woman who did not wish to sound like a bluestocking and who cast herself as a street-fighter ready to take on all the bullies of the neighborhood and beyond.

At the end of the conversation, I was sure of one thing: she would not be able to lead her party to election victory with a discourse that challenged the received wisdom. A tired and deeply conservative society such as Britain would not take risks with radical ideas from a revolutionary of the right.

During the week she spent in Iran, including tourism in Isfahan and Shiraz, Thatcher met a range of Iranian officials, including the shah. But she also insisted on meeting “citizens” such as university teachers, factory workers and shopkeepers. At the elite level, Thatcher did not leave a good impression. Foreign Minister Abbas-Ali Khalatbari found her “rather tiresome.” The chairman of the National Iranian Oil Company, Hushang Ansary, had a bit of an ideological back-and-forth with her on the role of government in modern societies. Thatcher claimed that Iran had “a half-socialist regime” because of the size of the public sector and the role of government in economic planning. Ansary retorted that a country could not be run like a shop and that government had to intervene in support of the weaker members of society.

Well, soon we were all proved wrong. A year after her visit, Thatcher was prime minister of Great Britain, starting a revolution designed to transform the hybrid model of society developed in Western Europe under different labels. In Britain it was called the welfare state. Germans knew it as the social market economy, and the French labeled it acquired rights.

The Thatcher revolution wanted to pull Western European social democracy towards the center, distancing it from Marxism. She succeeded beyond her wildest dreams.

The British Labour Party severed its last links with Marxism and adopted Thatcherism-lite under Tony Blair. The German Social Democratic Party (SDP) found the courage to push the reforms it had started in its Bad Godesberg conference to their logical conclusion. Even the French Socialist Party, though singularly reluctant to reform, had to change aspects of its overall strategy. In time, the British experience under Thatcher also led to reforms in Spanish socialism, while Italian socialism went further and disappeared altogether.

Thatcher also wanted to defeat the Soviets on the ideological battlefield, helping the West win the Cold War. Again, though the fall of the Soviet Empire was due to a wider range of causes, she ended up on the winning side. By the mid-1980s, basking in the sun of her victory over the Marxists who controlled parts of the British trade union movement, and having scalped Argentina’s military despots, Thatcher was at the peak of her glory. Once again, the Newtonian law that “what goes up comes down” started to operate.

By the end of the decade, the limelight of history had shifted away from Thatcher. Soon, she was forced to retire as the longest-serving British Prime Minister in the 20th century.

By all accounts, Thatcher succeeded as much as any conviction politician could in a modern democracy. She could attenuate some of society’s ills without curing them—perhaps no one can. Her genius was in the judicious use of the powers at her disposal. Unlike most other politicians in Western democracies, she did not want to be in office without power. Where most Western politicians were content to float—often on the surface—she wanted to swim, even against the tide.

It is hard not to admire her achievements. And yet, it would be wrong to exaggerate them. In human societies nothing is decided once and for all; the pendulum does not stay on one side forever.

The day Thatcher died, Britain’s largest trade union announced it was planning a general strike, the first since 1926. One wonders what Thatcher might have thought of that.