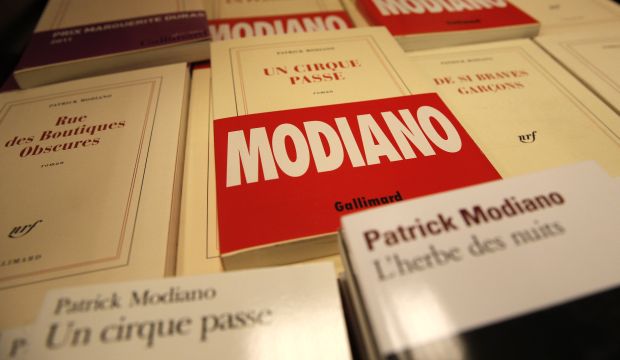

Books by French novelist Patrick Modiano on display in a Paris bookstore, on October 9, 2014. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena)

Let me confess at the outset that I am happy that Patrick Modiano has won this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature. In fact, the choice of Modiano may be a sign that the Swedish Academy is breaking out of the fog of political prejudice that had affected its judgment for decades.

Since the 1990s at least, the Nobel Prize for Literature has almost always gone to writers and poets of a certain political profile. They had to be at least moderately left-wing, clearly anti-American, and better known to elites and the cognoscenti than to the public at large. With few exceptions, all, including Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, the last French writer to win in 2008, have fulfilled those conditions.

Modiano, in contrast, is not any of those things. He is first and last a writer. Steering clear of fashionable politics, he can’t be labelled either “left” or “right.” Nor could he be suspected of anti-Americanism, if only because he is intelligent enough to know you can’t be for or against a nation at all times and on all issues. More importantly, perhaps, Modiano is not only appreciated by critics, including the Parisian glitterati, but has also been a moderate bestseller for more than three decades.

A real writer who also sells many books merits celebration, just as the Swedish Academy has done in Modiano’s case.

I first came across Modiano in 1978 when his novel Rue des Boutiques Obscures (literally, “Street of Darkened Shops,” translated into English as Missing Person) was published. At the time there was a consensus in literary circles in Paris that the French novel, and in fact the novel in general, had died, at least in its classical forms. Writers like François Mauriac, André Gide, and even Albert Camus, all of whom had received the Nobel Prize for Literature, appeared to belong to an age long gone by. The fashion, at the time, was that of “le nouveau roman” (the new novel), a series of works published by Les Éditions de Minuit in Paris. Here, the idea was to steer clear of telling any story at all and, instead, focus on the deconstruction of the human experience through games played with language. The big thing about “nouveau roman” was that the reader should not quite understand it, while pretending it had depths beyond human understanding.

Fashionable producers of “nouveau-roman”—I am reluctant to call them novelists—included the colorful Alain Robbe-Grillet, the queen of the bizarre Nathalie Sarraute and, at a higher level, Michel Butor and Claude Simon, who came close to being serious writers.

And then here was Modiano, a shy young man at the time, born in 1945 in the industrial Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt, who was clearly swimming against the literary tide.

To start with he wanted to tell a story with twists and turns that at times brought it close to a thriller. In it, Guy Roland, working for a private detective agency, is trying to piece together a life story long buried under the debris of time. This was a page-turner with the reader constantly asking the magical question: Then what happened? It was not like Robbe-Grillet books, which one could abandon or resume at any point and at any time without having the slightest inclination to know what would happen next because nothing did.

Modiano was atypical for another reason. He wrote a disciplined classical French prose that was a far cry from the fashionable word-plays of the day while also shunning the argotic experimentation of writers such as Antoine Blondin in A Monkey in Winter, for example.

There was a third element to Modiano’s persona as a writer. He was just a writer, a full-time one. You wouldn’t see him in literary parties, or on television, or as a juror at film festivals. Even when you invited him to lunch he was reluctant to accept, true to the dictum: “You are either out to lunch or producing literature!”

Though many French critics decided to simply ignore Modiano, Missing Person ended up winning the Prix Goncourt, the most prestigious of French literary prizes.

Some critics asserted he would be a one-novel writer, soon to be forgotten. While others feared that, pushed into the limelight of fame and fortune, he would cash-in by churning out novels as fast as his publishers desired. The fact that Missing Person was Modiano’s sixth novel, which meant that he had already chosen his path, was ignored.

The critics were proven wrong. Over the past three decades Modiano has emerged from his cocoon with a new novel almost every two or three years, each novel a step in the slow but steady maturation of his thought and style.

In musical terms, Modiano’s work could be described as chamber music. His is not the epic style; in fact, he steers clear of grandiose subjects. He is interested in the details that shape every human being’s existence over years or decades. If he were a musician he would be Corelli, certainly not Wagner.

Modiano’s principal theme is that of identity, lost and found and lost again. In his 1995 novel, Du Plus Loin De l’Oubli (translated into English as Out of the Dark), the narrator recalls a brief love affair 30 years earlier that had reshaped his life. Fifteen years after his break-up with his beloved, the enigmatic Jacqueline, the two meet again. This time, however, Jacqueline denies having ever known him. In the dreamlike atmosphere of the novel, the narrator wonders whether he is who he thinks he is, and whether Jacqueline ever existed.

Yet another theme in Modiano’s work is the belief that something done can’t be undone, and that we all, in fact existence as a whole, is part of a narrative told and retold. Modiano comes close to the Nietzschean concept of “eternal recurrence,” according to which what goes around comes around ad infinitum.

It was, perhaps, in that spirit that Modiano wrote his first novel La Place de l‘Etoile (Etoile Place), patterning its central character on his own Italian–Jewish father who had allegedly collaborated with the Nazis during the German occupation of Paris. The book angered Modiano’s father to the point that he tried to buy all the copies, around 500, to prevent anyone from reading it. At one point, the elder Modiano even called the police to come and arrest his son. Fortunately, that didn’t happen.

Modiano’s canvas is deliberately restricted to Paris, a city that provides the location of all his novels, although it is also used as a base for travels, always in search of identity, to many other places from Rome to Polynesia. “Without Paris, I wouldn’t have been a writer,” he likes to say. “Anyone living in this city is already on the way to becoming a writer!”

Even then, Modiano’s Paris is often limited even further, as he focuses on the left bank of the Seine (La Rive Gauche) where he has been living close to the Church of Saint Sulpice, the location of Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, in the heart of the Latin Quarter.

Modiano says he owes his attachment to “good classical French” partly to Raymond Queneau, himself a famous author, who happened to be Modiano’s math teacher at secondary school. Queneau told Modiano he would not become a good mathematician but had the potential to become a great writer.

Modiano says he has been permanently affected by his turbulent childhood that included the long disappearance of his father, the death of his brother Rudy aged 10, and the sufferings of his Belgian mother, a story he told in Un Pedigree (A Pedigree), a sort of ante-memoir published in 2005.

The theme is used in several novels, including L’Herbe de Nuit published a couple of years ago and examining the possibility of rewinding the life of a murderer in search of lost innocence. Childhood and the ambiguous role of the mother is a theme in Le Petit Bijou (The Little Jewel) while Une Jeunesse, published in 1981, is built around a lost youth.

Modiano has also tried his hand at writing film scripts, albeit with limited success. However, he has revealed himself as a powerful investigative reporter with his novel-cum-reportage Dora Bruder, published in 1977. In it he investigates the disappearance of a Jewish girl in Berlin in 1941, as announced in a small ad in a newspaper. Where did the teenage Dora go? What happened to her? The narrator embarks on a detailed investigation by using tiny scraps of information. By doing so, is he trying to come to terms with his own “lost years”?

What is going on? What happens next? Well, you have to read Modiano.