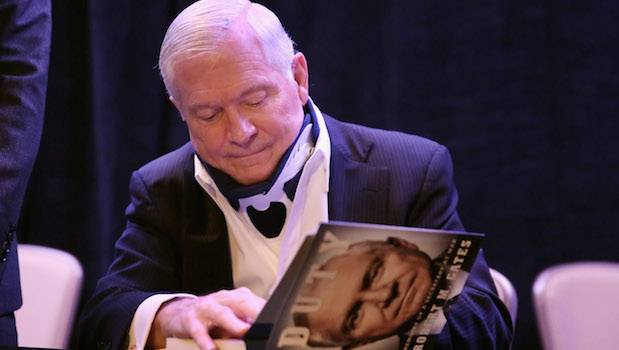

[inset_left]Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at WarBy Robert M. GatesKnopf, 640 pagesNew York, 2014[/inset_left]

If asked, we could all imagine an impossible job. However, few of us are likely to run into the experience in real life. One man who did is Robert M. Gates, one of the longest-lasting bureaucrats the US political machine has trained and deployed over more than half a century. Most of Gates’ career under eight successive presidents took shape in the shadows, as deputy director and then director of the CIA.

Although a protégé of President George H. W. Bush, Gates managed to maintain a non-partisan profile, earning the sobriquet “a man for all seasons.” In 2009, Gates appeared to have left all that behind to concentrate on his long-time dream of serving as college dean in his native Texas. It was not to be. Newly elected President Barack Obama, a man who owed much of his success in the 2008 presidential election to an almost indecent hatred of President George W. Bush and the Bush family in general, called Gates, their most loyal associate, with a strange invitation. Obama wanted Gates to become Secretary of Defense.

Gates’ new book: Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War is an account of the experience that unfurled when he accepted Obama’s invitation and entered the new Democrat administration. Gates does not say, but it is a sure bet that he obtained Bush Senior’s approval first. This was not the first time that a new and inexperienced Democrat president would invite a leading Republican to serve as Secretary of Defense; Bill Clinton had done the same with Senator William Cohen. The interesting thing is that almost all of America’s wars since the 1940s were started by Democrat presidents and ended by their Republican successors. Obama was an exception: he was a Democrat trying to end two wars, in Afghanistan and Iraq, started by a Republican President. Obama wanted Gates to supervise the ending of those wars for him.

There are, of course, many different ways of ending a war. One could simply run away or even surrender to the enemy. One could also end a war by winning it. What was original about Obama was that he did not favor of any of those options. He wanted to make the two wars appear to have been “tragic mistakes,” confirming his presidential campaign theme, but in a way that would enable him to claim victory nonetheless.

Without saying so directly, Gates portrays Obama as a hypocrite, if not an outright charlatan. Here was a president who would make all the right noises about the less important aspects of any issue but was utterly in the wrong about the essentials. “I never doubted Obama’s support for [our] troops, only his support for their mission,” Gates writes. This is a strange statement if only because, when translated into plain language, it means that Obama sent the troops that he supposedly supported into harm’s way while all the time secretly hoping they would fail.

Gates illustrates Obama’s bizarre bent of mind with a narrative of a crucial conference attended by the president and General David Petraeus, then commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan. “As I sat there,” Gates writes, “I thought: the president doesn’t trust his commander, can’t stand [Afghan President] Karzai, doesn’t believe in his own strategy and doesn’t consider the war to be his.” Obama was more interested in neutralizing Petraeus as a possible Republican presidential candidate and putative rival in 2012. That meant Petraeus should not be allowed to claim a military victory in either Iraq or Afghanistan. At the same time, Obama hated Karzai because he regarded the Afghan president as a “creature of Bush.”

Running in filigree throughout this absorbing book is a sense of outrage. Those who know Gates closely know he is a cool and composed man, expert in hiding his emotions in the manner of the proverbial, now-extinct Englishman from the Victorian era. In his book, however, Gates sounds more like an angry young idealist who has had his illusions shattered.

One such illusion was that someone who was elected President of the United States should at least likethe United States. It is clear that Obama does not. Another illusion was that policymaking in Washington was all about advice and consent. Under Obama, however, decision-making is concentrated in the person of the president as never before. Vice-President Joseph Biden emerges as a political version of Iago, whispering suspicions into the ear of the president. “Beware of the military,” Biden keeps whispering. “Don’t trust the military.”

That tendency has only been reinforced by the departure of the few heavyweights, including Gates, that Obama attracted during his first administration. Today, the Obama administration consists of a quartet of former senators with absolutely no remarkable achievements to their name. Biden’s case is especially interesting. He has been involved in foreign policy issues for almost 40 years, and has been consistently wrong on everything, from his support for the Khomeinist uprising in Iran to his opposition to pushing the Soviet Union’s back to the wall in order to end the Cold war.

In Duty, Gates is not gentle towards the American congressional elite. He describes members of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, then headed by John Kerry, as “rude, nasty and arrogant.” He gives us the spectacle of corrupt and cynical US politicians lecturing Iraqi or Afghan politicians against corruption and mismanagement. One issue leaves the reader’s curiosity less than satisfied. It considers the massive reorganization of the American military machine launched in the final years of the Bush administration and speeded up under Obama. Gates offers only a sketchy account of the rationale behind the massive cuts in the defence budget, including the technological scaling-down of the US Air Force and growing dependence on remote-controlled drone operations favored by Obama.

Dutyalso offers a mass of anecdotal material regarding Obama’s strange behavior as president and commander-in-chief. But it does not tell us why Obama is behaving in the way he does. Obama himself has offered some clues in his countless speeches. The latest clue came in Obama’s speech during a memorial service in Johannesburg for South African leader Nelson Mandela. In it, Obama said he first thought of seeking the US presidency after learning about Mandela and his “struggle for freedom.” In other words, Obama never believed in the mythology of “the American dream” and its attendant folklore of freedom and equal opportunity. For him, the US and South Africa under Apartheid were cut from the same cloth. Such a country has no business going around the world preaching freedom and democracy, let alone using its military might to topple vicious regimes such as the Taliban in Afghanistan and the Saddamites in Iraq. Gates reports that Obama was never interested in showing the slightest support for the Syrian people’s pro-democracy uprising. Instead, Obama was pursuing his dream of reaching an accord with the mullahs in Tehran. While Bashar Al-Assad was massacring Syrians in their streets, Obama was busy writing his five unanswered letters to Ali Khamenei, the “Supreme Leader” of the Khomeinist regime in Tehran.

Obama believes that the US has done wrong to many nations, including Russia that lost its Soviet Empire and superpower status because of American perfidy. What the world needs, therefore, according to Obama, is the taming of the US rather than letting it claim new victories in Iraq, Afghanistan, or for that matter, Syria.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks