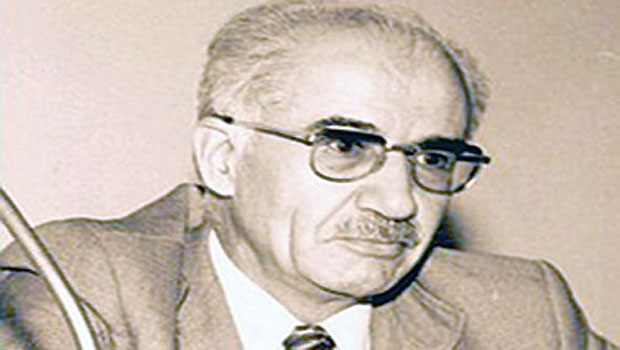

File photo of Yahya Sadeq-Vaziri (AAA)

London, Asharq Al-Awsat—A man for all seasons. This is how Iran’s intellectual elite knew Yahya Sadeq-Vaziri who died in Tehran aged 101 on Wednesday.

The sobriquet fitted a remarkable man with a remarkable life.

Sadeq-Vaziri was born when Iran was ruled by the Qajars, a Turcoman tribe who had seized the crown at the end of the 18th century. He had just graduated from Quranic school when a new dynasty, the Pahlavi, was installed by the Constituent Assembly in 1925. A witness to all of the tumultuous events, including two World Wars, a civil war and a revolution, that composed Iran’s contemporary history Sadeq-Vaziri never thought he would end up as part of it even though as a footnote.

However, in February 1979 he became just that when he resigned from the government of Shapour Bakhtiar, the last prime minister appointed by the Shah.

In Bakhtiar’s Cabinet, Sadeq-Vaziri had served as Minister of Justice.

Within days, Bakhtiar’s government collapsed amid revolutionary chaos led by Shi’ite clerics determined to seize power.

When he resigned Sadeq-Vaziri became the last Sunni Muslim to serve as a Cabinet minister in Iran.

Sadeq-Vaziri was born in Sanandaj, capital of the Iranian province of Kurdistan into a distinguished family of scribes and administrators with a long history of service to local emirs from the Ardalan family. In the 19th century, the Sadeq-Vaziri clan extended its influence through several members who secured influential positions in the central administration in Tehran. Later, several members of the family became members of the Iranian parliament, often representing Kurdish constituencies.

Yahya Sadeq-Vaziri was among the first Iranians to attend modern secondary schools and, later, university created by Reza Shah. He was also among the first to graduate from the newly-created Faculty of Law in Tehran. After two years of national service in the army, Sadeq-Vaziri secured a post as assistant prosecutor in Tabriz, capital of the East Azerbaijan province.

That was the start of a stellar career during which he secured many key positions within the new system of secular justice inspired by Western European jurisprudence. Sadeq-Vaziri rose to be one of Iran’s most senior judges and also served as head of the Judges Disciplinary Court.

Sadeq-Vaziri’s career came to an abrupt halt in 1963 as a result of a dispute with the then Justice Minister Muhammad Baheri over the creation of special courts to deal with politically motivated riots. Offered a sinecure as ministerial inspector, Sadeq-Vaziri preferred to retire from the civil service altogether, aged 51. He obtained a permit to practice as barrister but never did so. Instead, he spent his time writing a number of comparative commentaries on legal problems and helping moderate opposition groups develop a strategy.

In December 1978, as the Islamic Revolution raged, Sadeq-Vaziri accepted Bakhtiar’s offer of a Cabinet post. However, after the Shah left Iran on 16 January 1979, Sadeq-Vaziri argued that the Bakhtiar government no longer had a legal basis and should resign. Bakhtiar refused and tried to salvage his government until the end which came on 11 February. In the meantime, Sadeq-Vaziri had renewed his old contact with Mehdi Bazargan who was to become Khomeini’s first Prime Minister.

During Bazargan’s premiership, Sadeq-Vaziri led a mission to Kurdistan and, later, served as member of the committee to draw a new constitution.

He resigned from the committee once it became clear that, promoting the concept of Walayat al-Faqih, Khomeini wanted absolute power for himself and the Shi’ite clergy. That meant transforming non-Shi’ite Iranians into second class citizens.

Before Khomeini seized power, many Iranian Sunnis served in senior Cabinet positions including the ministries of the interior, foreign affairs, justice and agriculture.

The mullahs’ rule broke that tradition in 1979. Since then Iran’s estimated 10 million Sunni Muslims have been excluded from top positions in the civil service, the military, the diplomatic service and the public sector of the economy. They are also barred from seeking the post of the President of the Republic and that of the Supreme Guide.