“Where are the Arabs?” Hawi had asked at the time, the day Israeli tanks swept into Lebanon. “Who shall remove the stain of shame from my forehead?” Later that evening, he removed the “stain” by shooting himself.

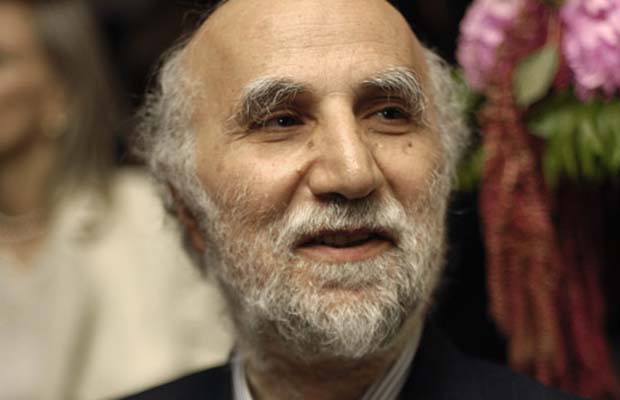

For Professor Fouad Ajami, Hawi’s suicide told a larger story, of Arab men and women who dreamed of modernity, but who despaired of their weakness, of their stale politics, of their stubborn tradition and dangerous sectarianism. It was an astonishing essay, entitled “The Suicide of Khalil Hawi: A Requiem for a Generation,” and the lead chapter in what I consider one of Ajami’s most important works, Dream Palaces of the Arabs.

For those of us who knew Professor Ajami the man, not the caricature, we understood that the Hawi essay was deeply personal. He, too, despaired of the Arab political condition. In Dream Palaces of the Arabs, he laid bare his world view.

“In the privacy of their own language, when Westerners, Israelis, ‘enemies,’ and ‘Orientalists’ were not listening in, Arabs spoke with candor, and in code,” Ajami wrote. “They did not need much detail; they could speak in shorthand of what had befallen their world. The trajectory of their modern history was known to them.”

The story they told was one of a fall.

From the “cultural and political tide in the 1950s,” a tide that brought “growing literacy, the political confidence of mass nationalism, the greater emancipation of women, a new literature and poetry that remade a popular and revered art form,” came “the shattering of that confidence a decade later in the Six Day War of 1967,” and a new world was made.

In that new world, Ajami wrote, “the young had taken to theocratic politics; they had broken with the secular politics of their elders.” And for Fouad Ajami, looking back on that moment nearly two decades later, he wrote that “at the heart of this extended narrative is the impasse, the generational fault-line, between secular parents and their theocratic children.”

In that new world, Khalil Hawi committed suicide on his balcony in West Beirut, and the Arab political condition, particularly in the principal cities of Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus and Beirut, coarsened. Perhaps that is why Ajami clung to the poets and the novelists. They offered him hope.

I knew Fouad Ajami as a student at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Before I traveled to Egypt for a summer of Arabic study, I asked him what I should read: “I have twenty books for you: all of them Naguib Mahfouz.” He once told me that the few days he spent in the company of Naguib Mahfouz before his death were one of the highlights of his long career.

Fouad Ajami was a prolific writer, but his books held a special place in his heart. They told the stories he wanted to tell, and were laced with a sense of regret and pathos.

In The Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon,, published in 1978, Ajami wrote: “Musa al Sadr led his Lebanese followers at a time when they were beginning to make a claim on their country. He vanished and left them with a text and a memory and some institutions at a time when the country as a whole had become a ruined place. Young men behind sandbags, with their Imam’s posters, defend the ruins that are theirs and their sects. A measure of equality has come to Lebanon.”

In The Arab Predicament, published, 1981, he writes: “There is no ‘fun’ in the material handled here: It is a chronicle of illusions and despair, of politics repeatedly degenerating into bloodletting, of imagined transformations followed by despair that there is some immutable core that disfigures it all, that devours all good intentions, that mocks those who would try change things.”

In Beirut: City of Regrets, published in 1988, he laments the state of civil war in Lebanon, writing, “Before the fall, before the terrible ‘events,’ and the political ruin of the last decade, there were tales of Lebanon; tales of a small, mountainous country by the Mediterranean; of Beirut, the charmed city where a dramatic mountain range descended to the sea. There were tales of an enterprising people who lived by their wits and who reconciled the austere Arabian–Islamic truth of their East with the ways and the truth of the West.”

And in Dream Palace of the Arabs: A Generation’s Odyssey, published in 1998, he presaged the Egyptian uprising of 2011: “There is no law of social peace, no fated happiness or civility in any land. There had been lamentations on the banks of the Nile and times of celebration. There is a decisive role here for the human will monitoring the cycle of life and all it brings by way of seasons. It is not enough consolation to pay tribute to the good soil and the patient river. Those gauges on the banks will have to read and watched with care.”