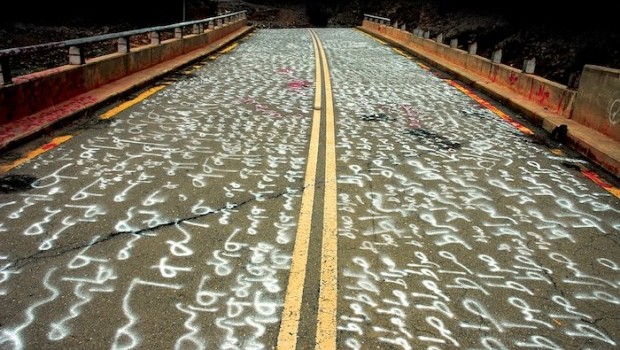

Abdulnasser Gharem“The Path” (2007), UV-curved virtu digital print on white aluminumCourtesy of the Ayyam Gallery

From his most famous pieces is the series Concrete, in which blocks of different shapes and colors are stamped with words and phrases. The message of each piece in the series is the same: they are borders and boundaries, roadblocks to human dreams and desires, molded by mentalities that do not give space for free minds to make independent choices. This important theme runs throughout Gharem’s work, which makes heavy use of text and calligraphy—but each piece carries its own message and meaning far deeper than the letters written on them.

The exhibition at London’s Ayyam Gallery begins with Gharem’s 2007 photographic series Manzoa, which means both “removed” and, in this context, “demolished.” In this series, Gharem interacts with the residents of one of the poorest Saudi neighborhoods, Jizan. The villagers had their homes marked for demolition as part of a development plan and had been compensated for the land, but they could not bring themselves to leave their homes and thus kept living in the ruins of their old village.

Abdulnasser Gharem “Concrete” (2008), Industrial lacquer paint on rubber stamps on 9mm plywoodCourtesy of the Ayyam Gallery

He added that he was interested in the village for a decade before the residents opened up and felt comfortable enough to reveal their secrets to him.

Manzoa carries many meanings for Gharem: one of this most important is its representation of the bureaucracy that controls the lives of many people today. But he also says it carries a message of belonging, which says is “the main message of the piece.”

Pointing to the photographs, Gharem adds, “The place has become a shadow of itself, with broken walls and the remains of old furniture. In the pictures, you can see a stack of old televisions and people harmoniously standing to one side.”

What does this situation represent? He answers with a sad smile drawn across his face: “Any normal viewer will see the photographs as a piece of the Arab world. The subject fits today’s reality, for we can see images of destruction and the remainders homes in all the Arab countries today.”

Next to the photographs is a piece composed of Arabic numbers placed side by side. You stand in front of it and wonder, trying to solve its puzzle, but it is not easy. The artist points to it, saying that it is part of Manzoa. “These numbers are the numbers of the homes demolished in the village, which I collected. It is all that remains from them—mere house numbers,” which the artist relates to the ideal of a nation.

In another part of the gallery is series of rubber stamps—one of the Saudi artist’s more familiar works. It has a simple, but powerful, meaning. The stamps have been customized by Gharem with phrases such as “Amen” and “God willing . . . more commitment.” Another stamp is imprinted with the phrase “Licensed by the Shura Council.”

The stamps carry a unique aesthetic appeal. The handles are covered in exquisite Islamic inscriptions, but they carry a completely different message from what appears at the surface, expressing a state of immobility and inaction.

Similarly, the concrete blocks stand out in the exhibition and are one of the favorite themes of the artist. “They symbolize to me the barriers to thought and discussion, as if someone is warning you or blocking your way [but] you don’t speak or challenge it,” he told Asharq Al-Awsat.

The rest of the pieces are inscribed with words, some with literal meanings and others which cannot be understood. They read madfoa (“paid for”), wasel (“receipt”), haam jedan (“very important”), and ajel jedan (“very urgent”). Gharem explains that the phrases symbolize that “human life is governed by this bureaucracy.”

From his more recent works on display in London, one in particular draws attention. At first glance, it is what appears to be the niche of a mosque, with its exquisite inscriptions—but on closer inspection the viewer notices a tank with a yellow flower in its gun barrel.

Perplexing work? Not exactly. In a similar piece, Camouflage, violence is disguised in a manner that hits close to home. Gharem explains that “these motifs symbolize the growing sectarianism and the reality and sentiments after the Arab Spring, in particular the use of religious language. The name of the piece is Camouflage; the tank is hiding behind beautiful Islamic art. This represents our future and the role of the military in Libya and Egypt.”

In a similar work, a dome of a mosque is split into two halves, half of it painted green and the other half blue. You might imagine it to be from the helmets of soldiers of the old Islamic armies—in which case, you have guessed correctly. “This piece also symbolizes sectarianism, Sunni and Shi’ite, which makes Muslims pick sides, but with what sense is a Muslim asked to fight?” asks the artist.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks