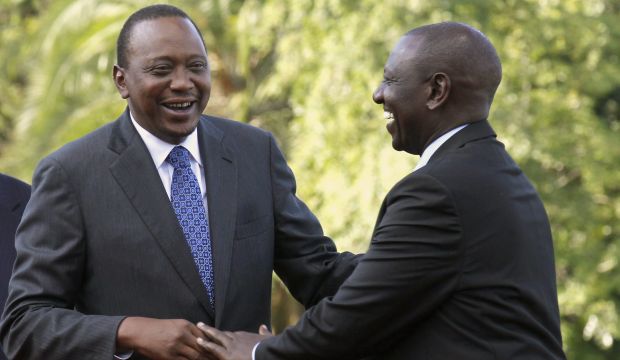

Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta (L) shares a moment with his deputy William Ruto after Kenyatta’s case at the ICC was dropped, in Nairobi, on December 5, 2014. (Reuters/Thomas Mukoya)

Amsterdam and Nairobi, Reuters—Prosecutors dropped charges of crimes against humanity against Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta on Friday, marking a failure for the International Criminal Court in the highest-profile case in its eleven-year history.

Judges in The Hague had on Wednesday given prosecutors a week to decide whether to proceed against Kenyatta, who was accused of fomenting ethnic violence after the 2007 election, or withdraw the charges.

Prosecutors have said Kenyatta, the first sitting president to have attended a session of the court, used his powers to obstruct the investigation, especially since becoming head of state last year. Kenyatta’s lawyers denied this.

The collapse is a blow to the court, which has secured only two convictions, both against little-known Congolese warlords, and has yet to prove it can hold the powerful to account.

Many Africans accuse the court of unfairly targeting their continent, while a lawyer said it had failed victims of the post-election bloodshed in which 1,200 people were butchered.

“The evidence has not improved to such an extent that Mr Kenyatta’s alleged criminal responsibility can be proven,” prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said in a court filing.

Kenyatta received the news at a meeting of Kenyan officials and business executives, who applauded. Some hugged him.

His reaction, “One down, two to go,” referred to his wish to see similar charges dropped against his deputy, William Ruto, and a Kenyan journalist.

Diplomats say the case has been a distraction for the administration, despite official denials. But the economic impact has been limited, in part because most investors have long thought the case against Kenyatta was falling apart. There was no immediate market reaction.

The court did not acquit Kenyatta, so charges could be brought again if more evidence becomes available.

But the case against him struggled in the court, with prosecutors saying star witnesses had been intimidated into withdrawing testimony, a charge Kenyatta’s lawyers denied.

Fergal Gaynor, counsel for the victims, said in a statement that the withdrawal of charges would disappoint the estimated 20,000 victims of crimes charged in this case.

“It is regrettable that the victims have received almost nothing from the entire ICC process,” Gaynor said.

Kenyatta’s supporters welcomed the news, saying that continuing the case re-opened wounds dividing ethnic groups. But some relatives of those killed said justice was not served.

“We now know that there is justice for the rich and justice for the poor,” said Irene Akoth, who lost a brother in fierce post-vote violence that raged in Naivasha, northwest of Nairobi. “There is nothing we can do, we have to move on.”

Analysts said dropping the case against Kenyatta, an ethnic Kikuyu, while proceeding against Ruto, a Kalenjin, could create tension in the ruling coalition in a country where politics usually follows ethnic allegiances.

“It means there will be some careful balancing from the coalition,” said Clare Allenson of the Eurasia Group.

The two men publicly work very closely together and have both recently been calling for national unity after a spate of Islamist militant attacks.

Among the ICC’s most prominent indictees are Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir, wanted for genocide in Darfur, who remains at large and in office, and Saif Al-Islam Gaddafi, son of Libya’s former leader, whom Libyan authorities have refused to hand over.