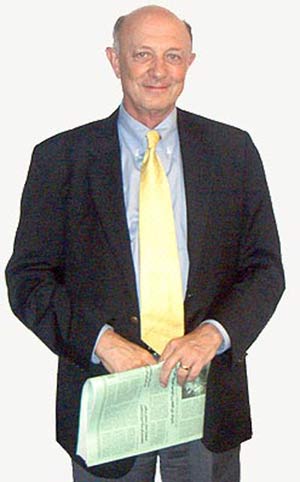

Asharq al Awsat Interviews Former CIA Director James Woolsey

(Q): There is a perception in the Arab world that the US has failed in Iraq. what are your thoughts on that?

(A) Nonsense. The Shia and the Kurds, which is 80% of the country, are having their portions of the country function reasonably well. The election January 30, which the Sunnis largely boycotted, has produced now an interim government and a constitution. The constitution will be voted on in October. If the Sunnis again boycott the election, the constitution will come into effect. If the Sunnis vote, they would need to have three provinces show a two-thirds majority or more against the constitution in order to keep it from coming into effect. They might be able to do that, but I think it will be difficult for them. So I think there is a better than 50-50 chance that, after October, we will have an approved Iraqi constitution pointing toward national elections in December. Now it is true that the remnants of Baathist, augmented by Saudi and other terrorist suicide bombers, are continuing to kill people and to blow up portions of the infrastructure in Iraq. But we are also training more and more each day Iraqi troops who are taking over, gradually, more and more responsibility. So although this is not a sure thing, I think the probability of Iraq moving into being a functioning democracy – except for some aspects of Lebanon some years ago, it would really be the first functioning democracy in the Arab world – will be a remarkable development. And the people who are saying that failure has already occurred are most likely the elites in government and in the Arab world who do not want democracy, who do not want a Shiite majority democracy particularly, and who would like to retain their own power without having to face their own people in elections. I think that’s the people you were asking me about.

(Q) Are Iraq’s neighbors cooperating with the US in a satisfactory manner?

(A) I think that Iran is certainly not cooperating. Iran does not want a Shiite majority democracy in Iraq because that would mean that the people of Iran might be able to govern themselves instead of being governed by this totalitarian Wilayat Al-Faqeeh. I think the government of Jordan is being somewhat helpful. I think that the government of Syria is not being helpful at all, that it is a major part of the reason for the infiltration of terrorists into Iraq. I think the government of Egypt is moving toward its own first partially democratic elections and is being somewhat helpful. And I think the government of Saudi Arabia has not been able to constrain some of its religious leaders such as the twenty-nine Imams who issued the call for suicide killers in Iraq. And as a result, the majority, according to most reports, of the suicide killers who come into Iraq are Saudi. So I think that although the government of Saudi Arabia is doing a reasonably effective job of fighting the Islamists, salafis if one wants, al-Qaeda, inside their own country, they have not effectively constrained terrorists from going into Iraq.

(Q) Do you think the US will be able to win the war of ideas? Seems like Alhurra TV and Sawa Radio are short of attaining that objectives.

(A) We should not be trying to win popularity or win, as some people have put it, hearts and minds in this part of the world. We should be trying to free hearts and minds. Agents of change, whether it’s in the US or anywhere else, are often not popular, and that’s alright. We’re not in a popularity contest. We are in an effort to try to help the people of the Middle East; most of whom I believe would like to see democracy and the rule of law prevail over people like al-Qaeda and Zarqawi and the salafis and people of other anti-democratic views.

I think that the Middle East will be for some time a battle ground between the ideas of democracy and the rule of law on the one hand and the ideas of the Salafis and totalitarians on the other, totalitarians such as the Baathist. We should, in the world of ideas as well as otherwise, do everything we can to help the forces of democracy prevail. I think we have a good chance of having that be the case in Iraq. I think we’ve seen steps in that direction, important ones in Lebanon in the last few months. We’ve seen some steps in that direction in Egypt with the election. We’ve even seen a little bit of a step in Saudi Arabia with the election of half of the local council members, unfortunately with only men voting. But we are seeing changes in Libya, in giving up their weapons of mass destruction and becoming open to real economic development and even I think in time some political change.

Change is in the wind in the Middle East, and some of that wind is blowing from the direction of democracy and the rule of law. Walid Jumblatt said, for example, a short time ago that it really was only because of the American and our allies overthrow of Saddam Hussein that these ideas of democracy and the rule of law were beginning to spread in the Middle East. So we should not want popularity. We should not be trying to get people to be pro-American. Much better that Turkey, being a real democracy as it is, decided to disagree with the United States about letting our division go through Turkey, our soldiers, in the war against Iraq. Much better that Turkey be a democracy in which the people can make their own decisions, than that there be a Turkey ruled by the military, say, that might be more willing to agree with the United States. Were not seeking agreement, we’re seeking freedom for the people of the region.

(Q) What if democracy brings the Islamists to power?

(A) Well it depends on what one means by Islamists. If it is someone who believes in having a political party of the sort that is now in power in Turkey for example – Turkey will have its next election schedule I’m sure. People argue about ideas. The current party may win or one that is more in the Attaturk tradition may win – I think that is fine. But if someone calls himself an Islamist and by that he means he wants to have only one election once, and then he and his friends decide how the country is to be ruled, then that, whatever it is called, is dictatorship. And that is not democracy and we should not count that as a step in the direction of democracy and the rule of law.

(Q) I mean by Islamists, for example, the Muslim Brotherhood

(A) Well I understand, from people how know far more about the details of the Muslim Brotherhood than I do, that there are some members of the Muslim Brotherhood movement, for example in Jordan, that would be likely to be supportive of continual election and democracy, and there are other members of the Muslim Brotherhood who would only want to hold one election once and then keep control. And the first, like the Turkish party now in power, as far as I’m concerned, are fine. And the second are ones we should oppose.

(Q) Why do you think all attempts to find Bin Laden, Zawahiri and Zarqawi have failed?

(A) I don’t know. It may have had something to do with the tactics that were used. It may have had something to do with the support for him by some of the tribes up there in Waziristan in the northwest frontier of Pakistan. Zarqawi was in Iraq apparently during the Afghan war, so we really had no chance to capture him until we moved into Iraq in the spring of 2003. And we’ll continue to look for all three, but the most important thing is for the people of the region to be able to get control of their own governments rather than having dictators and dictatorial kings rule them. Once that happens I think Zarqawi and Bin Laden and Zawahiri’s opposition to democracy will put them on the opposite side of most of the people of the region and perhaps someday we will capture them. But the most important thing now is to help these countries move toward democracy and the rule of law.

(Q) Reports in the Middle East said Bin Laden, or some of his followers are in Iran?

(A) I have seen such reports. I think it is sometimes the case that people put too much stock in the ideological roots of a movement and assume that if organizations grow from different ideological roots, they will never cooperate. I think that is nonsense. Totalitarians, people who want to dominate and rule, as Orwell put it, with their boot in everyone else’s face, like the Wilayat Al-Faqeeh in Iran, like Bin Laden and al-Qaeda, like the Baathist in Iraq and Syria. Even though they come from different intellectual roots, they have a lot more in common than otherwise. And I think it is perfectly possible for al-Qaeda to have worked with the hard-line elements of the Iranian government, to have worked with the Baathist in Iraq as well as Syria. And to use an example from European history, in the 1930s a lot of people said that the communists and the Nazis would never cooperate. Their movements came from different intellectual roots. They fought each other in the streets. They killed each other. They hated each other. But in 1939, Hitler and Stalin signed the Hitler/Stalin pact because they decided it was in their interests to divide up northern and northeastern Europe.

I think that totalitarians like the Wilayat Al-Faqeeh in Iran, like al-Qaeda and like the Baathist are going to cooperate from time to time. And it may be that at one time or another Bin Laden was helped by the Baathist in Iraq as well as Syria. It may have been from time to time they were helped by the Wilayat Al-Faqeeh in Iran. And someday the historians will sort all of this out. In the meantime, the important thing is to defeat the totalitarians whether they are Baathist or al-Qaeda or the Wilayat Al-Faqeeh.

(Q) Do you expect that the US will repeat Iraq’s example and use force to bring democracy to other countries in the Middle East?

(A) I hope that won’t be necessary. In 1945, there were twenty-five democracies in the world. Actually twenty democracies. Today there are one hundred and eighteen, eighty nine of them operating under the rule of law and another twenty nine or so that have problems with the rule of law, such as Indonesia, but nonetheless have regular and reasonably fair elections. So well over 60% of the world’s governments and well over 60% of the world’s people live in democracies. That’s been an extraordinary expansion in democracy in the last 60 years. Only three of those changes, set aside Iraq and Afghanistan for now, only three of those changes – Granada, Panama and South Korea – since 1945 were the result of American military action. In South Korea we defeated North Korea’s attempt to conquer the south, and after several decades of dictatorship, the south became a democracy. And in Granada and Panama we threw out dictators, and they became democracies.

But all of those other nearly one-hundred new democracies since 1945 came about in through all sorts of different ways. In Poland it was a solidarity movement and then the Pope who had a major hand in, ug…The Philippines it was people power. Sometimes the United States helped; sometimes we were on the sidelines. But in only about 3% of the cases of those new democracies coming about since 1945 was it done by American force of arms. So the fact that we are very much working for democracy and the rule of law in the Middle East does not necessarily mean that in any additional cases that it would have to be by the use of force.

(Q) As the US government embarked on winning hearts and minds of the Arabs, what role do you think Arab Americans could play? Or do you think they are looked at suspiciously after 9/11?

(A) The Muslim and Arab communities in the United States are different than they are in for example Europe. According to the Zogby poll, and Zogby is an Arab American, over 75% of Arab Americans are Christians, largely from Lebanon, some Kaldeans and from Iraq. The majority of American Muslims, substantial majority, are from South Asia. They are not Arabs. So the Arab Muslim population of the United States is quite small. Now I think that each of these communities and each of these groups have integrated into the United States in somewhat different ways, but we have historically had much more success in this country of integrating immigrant groups, becoming part of the American melting pot, than has been the case generally in Europe, where Muslim and Arab immigrants into Britain or France or Germany maintain far more of their own separate cultures and language and the like.

So I think that as a general proposition, here in the US, although it’s not perfect, our ability to integrate Arab groups, whether Christian or Muslim, and Muslim groups, whether from South Asia or from the Arab world, has been reasonably good. We have a number of wonderful Muslim Americans and Arab Americans who serve our armed forces and our government. Our commander in the Middle East, General Abuzaid, is an Arab American. So I think we have, as I said, a far from perfect record in this regard, but generally speaking we have not done too badly in integrating cultures from all over the world into our society here.

(Q) Four years have passed since 9/11 but there is still news of expected future attacks?

(A) You mean from the terrorists? I think the main reason we haven’t seen one yet is that we very heavily disrupted al-Qaeda’s operations by moving as quickly into Afghanistan as we did. They had a base of operations, training camps, laboratories for biological weapons, and on and on and on there, and we disrupted all of that by moving so quickly. I think that there are al-Qaeda cells I’m sure in the United States, but al-Qaeda has become I think considerably more decentralized and less under the firm hand of Bin Laden and Zawahiri than was the case when they had their base of operations in Afghanistan. It is still possible for there to be an attack, even a major attack in the United States, but I think we certainly slowed al-Qaeda up a great deal, to some extent by the war in Iraq, but principally by the war in Afghanistan.

(Q) Did you expected attacks like 9/11 when you were CIA Director?

(A) Well, not exactly, but on the other hand I have been out of the CIA for ten years. I left in January of 1995. At that point Bin Laden was one of a bunch of terrorists who hung out in Sudan. He had not yet issued his declaration of war about the United States. They had not even conducted the attack that they conducted later in 1995 in Riyadh on the reserve facility.

(Q) Did al-Qaeda play a role in the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993 around the time you were CIA Director?

(A) Oh, the first World Trade Center attack in 1993. Well, there is I think a question of the degree of which al-Qaeda as an organization was responsible for that. Certainly, we know that Ramsi Youseff was the ringleader and that Mr. Yassen, who is an Iraqi, returned to Iraq after the attack and was protected by Saddam’s government. Beyond that, a great deal about the organizational structure of the first World Trade Center attack is still I think somewhat unclear. It was certainly a very serious matter, but it was not something that at the time was tied to Bin Laden as an individual.

(Q) Are you satisfied with the recent re-arrangement of the intelligence operations? There are news of rivalries and differences.

(A) Well there is always bureaucratic rivalry and differences of opinion on some issues between the parts of the national security structure here. Normally it is not disagreement about extremely fundamental issues. It is disagreement about tactics. For example, both the State Department and the CIA were opposed to using the 97 million dollars that Congress set aside in 1998 when it voted for the United States to overthrow Saddam – Iraq Liberation Act.

Those two agencies were opposed to using the 97 million dollars to train Iraqi forces in the north of Iraq, and I think that was a real shame. Most of those forces would have been Kurds or Shia, well there would have been some Sunni, but I think we should have had them trained so that when the war came we could have had Iraqi units fighting alongside us just as the free French in 1944, small units but they were there, fought alongside the Americans and the British in liberating France.

That was a bureaucratic disagreement in which the State Department and the CIA were opposed to training the Iraqis in the northern part of Iraq, and the Pentagon tended, at least some people in the Pentagon, tended to favor it. So sometimes it is true that bureaucratic disagreements about tactics like that can have important long-range implications

But nobody should ever expect Americans to march in lockstep with one another. Our constitutional structure is designed to create disagreement between the branches, to have political parties that disagree, and we have had a history of pulling together and getting the job done when the threat was really serious as in the Civil War and World War II, under leaders like Lincoln and Roosevelt. But short of a massive international challenge of that sort, we do sometimes disagree with one another rather vigorously even while we’re carrying out important international operations like what we’re doing now in Iraq.

But no one should be surprised when Americans disagree with one another. Our whole governmental structure is set up to promote disagreement in order to preserve freedom.

(Q) How do you see the future of the US and Arabs relations.

(A) The only thing I would add is that Winston Churchill once said that the Americans always do the right thing but unfortunately only after they have exhausted all other possibilities. It’s a pretty good crack about Americans.

For many years, we have treated the people of the Middle East as if what we wanted them to do was to be polite filling station attendants. To pump the oil that we need and otherwise not to complain. Not to complain about their lack of civil liberties in the governments that they were ruled by. Not to complain. That was a bad approach. I think we’ve learned. Now some people may have wished that we hadn’t learned. But I think we have learned. I think what we’ve learned is that there is only one way to defeat these totalitarian ideologies like that of al-Qaeda or the Wilayat Al-Faqeeh in Iran or the Baathist that want to dominate other people and rule them and kill whom they want to kill and run their rape rooms as Saddam did. There is only one way to defeat that, and that is to ally ourselves with the people of the Arab world, and of the Middle East generally, who want to move toward democracy and the rule of law.

So I think that is now where we are and that is now where we will be for a long time. There will be setbacks, but I think that’s the course we’re embarked upon. And if twenty or thirty years from now the Middle East is largely, maybe not entirely, but largely democratic, operating under the rule of law, and because these countries are democracies there is a lot of argument and a lot of disagreement and a lot of people who say “we don’t like the Americans because they’re doing this wrong or they’re doing that wrong,” then that will be a great victory, because the most important thing is not whether people like us. The important thing is for the people of the Middle East to be free.