A Tale of Two Iraqi Cities

Irbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan may lie only 400 km north of Baghdad, but the difference in the recent fortunes of the two cities is startling.

As the hour-long flight from Irbil reaches Baghdad airport, formerly known as ‘Saddam International Airport’, the plane circles the runway several times before landing, protected by anti-missile batteries to ensure its safety.

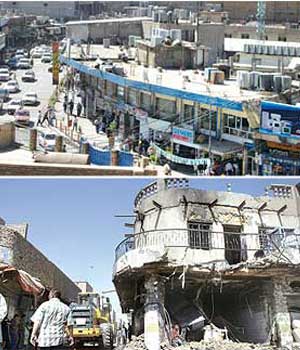

Looking towards Baghdad, a city now in ruin, I could see heaps of rubbish on its streets. I wondered what had befallen the city in which I was born and brought; its landmarks had disappeared amongst the engulfing smog. In the three years since the US occupation began, Baghdad had deteriorated rapidly. The look on visitors’ faces spoke at length of the sadness and sorrow that has come to dominate the Iraqi capital. Only those who were leaving had a smile on their faces. It seemed as if time in Baghdad had stopped at 7:05, when it came under US bombing on 9 April 2003.

Earlier, when I looked down on the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, I saw a city undergoing a construction boom with buildings peppered around the runway.

In Irbil, visitors are met with a huge billboard welcoming them to Kurdistan, written in Kurdish, Arabic and English. North of the current airport, a new runway and terminal are being built as part of ambitious plans to create a new truly international airport, capable of welcoming thousands of visitors a week to Irbil. As we rode towards the city, my companion Rawand Abdul Qader, an official in the Kurdistan regional government, pointed out a construction project, with plans to build deluxe private homes. “The finest square kilometer in Iraq,” a giant billboard read.

Dream Land’s director told Asharq Al Awsat, on condition of anonymity, “This project is aimed at investors. We started work last year and hope to complete building 1200 deluxe villas in 2009.”

“I always travel to Baghdad but I fear being kidnapped. I have already been kidnapped once. I was released after paying a considerable ransom. We chose Irbil for our project because it is more stable than other Iraqi cities. Investors are also welcome here and the regional government does not interfere and does not allow financial mismanagement,” he added. More buildings that are new lie behind the construction site and these were recently built by an Iraqi Kurd who returned from Europe to invest in his city.

On the other hand, no investment projects are currently lined up in the Iraqi capital. According to Ammar al Biyati, a civil society activist, “The rate of unemployment, with the exception of Iraqi Kurdistan, is between 68% to 73%. If we add to that the number of professionals who are employed in menial work as taxi drivers or builders for example, the unemployment rate becomes much higher.”

In Irbil, Dream Land’s director said, “We are looking to hire more people, especially those with technical skills. There is no unemployment to speak of in Iraqi Kurdistan. Around three quarters of the work force comes from other areas of the country, such as central and southern Iraq. Whereas the average salary of a construction worker in Baghdad is 15 thousand Dinars, they can make up to 20 dollars a day in Kurdistan, more than a fourfold increase.”

“The construction boom is cased by the stability and security here, as well as the return of Iraqi Kurds from exile. I have returned from the United States to Irbil and obtained a piece of land and a small loan from the government to build a house in the suburb of Ayin Qawa, which I last visited in the mid-1980s. I discovered it has been transformed into a rich neighborhood full of flowers and social clubs.”

I enter Babel Hall in Baghdad’s international airport and immediately, I am struck by the pervading silence. Once a bustling arrivals hall, full of visitors and families awaiting their loved ones, it now stands almost deserted.

Until recently, the six-mile stretch of road leading from central Baghdad to the country’s main airport used to be known as “the road of death,” one of the most dangerous stretches of highway in Iraq, if not the world. Many attacks occurred along the stretch of road and several people lost their lives, before the US army beefed up security and heavily fortified it, as the taxi driver, a young Iraqi called Ahmad, explained to me.

In the past, this road used to be one the most beautiful in the capital and was frequently used by Saddam Hussein to travel to his palaces in al Radawaniya, surrounded by lakes. Nowadays, like other roads in Baghdad, it appears neglected and is full of craters, evidence of bombings and explosions.

On our way to the capital, our taxi stopped to let a US patrol of several Humvees go through. On the back of each vehicle, a sign warned of imminent death if anybody dared to get closer than 200m.

However, in the streets of Irbil, no foreign troops are to be seen. Security is maintained by the local police and guards distinguished by their uniforms. Many used to belong to the Peshmerga forces whose duty is no longer to fight Saddam’s regime in order to defend the rights of the Kurdish people.

Every day, dozens of beheaded bodies are discovered across Baghdad and its suburbs. In the latest statistics announced by the Ministry of Defense, 263 Iraqi civilians were killed and 310 were injured in 63 separate “terrorist” attacks in the last seven days. More than 1051 Iraqis were the victims of terrorism in the month of May alone, another study revealed last week.

The security situation is markedly different in Iraqi Kurdistan, with the last terrorist attack occurring more than three years ago. According to Nechirvan Barazani, prime minister of Kurdistan’s regional government, terrorists “are trying to create problems and bring terrorism to Kurdistan but they have no place amongst our people and our region. We have succeeded in this regard thanks to the awareness of our security services and ordinary citizens. We feel secure in this regard.”

Ibril’s streets are crowded with cars and pedestrians as policemen try to direct traffic until midnight each day. Its packed markets stay open until 10pm; consumers can find all the latest electrical equipment they might need, including computers, televisions, freezers, washing machines, satellite dishes, clothes and other household essentials. Families stay up into the night and enjoy the city’s restaurants and cafes, where they can hear traditional Arabic and Kurdish songs, without fear of bombings or attacks.

Every Monday and Thursday evening, the streets of Irbil are witness to dozens of wedding celebrations, with cars decorated with ribbons and roses ferrying the bride and groom to one of the capital’s fancy hotels or nearby summer resorts, such as “Saladdin” or “Jandiyan”.

“Life here in Irbil is very normal. People stay up in the early morning. In Baghdad, we used to fear leaving the house after sunset. We hope normal life returns to Baghdad so we can visit it again. We have good memories there,” said Madhat Mandalawy, the 52-year-old minister in the regional government.

For her part, Nisrine Bikr, a secondary school teacher, recalled visiting Baghdad every summer with her family. “But we no longer go because of the bad security situation. The opposite is now happening and our cousins and friends from Baghdad now visit us to enjoy Kurdistan’s beautiful nature and atmosphere and enjoy the security and stability in Irbil.”

An Iraqi airways employee on a visit to Iraqi Kurdistan told Asharq Al Awsat she hoped the length of her trip would be extended and welcomed the chance to leave the carnage in Baghdad behind, if only for a few days. The Iraqi capital, she explained, lacks “electricity and security. We cannot leave our houses in the evening. Here, in Irbil, I can go out whenever I want. There are spaces for families to pass the time and shopping areas. The Kurds are, by nature, good people and have cooperated with us.”

Indeed, the streets of Baghdad are empty after 6pm, when the city is transformed into a battleground, with the sounds of gunfire and bombing echoing in the distance. Public and private occasions are celebrated midday in Baghdad, especially weddings, which have been targeted by suicide bombers in the past. Even government-sponsored activities, such as conferences or cultural events, have to finish before dusk.

Life in the two capitals could not be more different: one is the daily victim of death and destruction while the other flourishes and enjoys its change of fortune.