New York – At times they’re friendly and persistent, arriving on the scene to poke a nose into the news-gathering operation. Other times they keep their distance, appear aloof, are hard to pin down. Some are easily wooed with gifts: a warm meal, a cool drink. When flattery fails and aggressions surface, employing a muzzle is tempting but ill-advised.

I’m referring, of course, to foreign bureaucrats. Wait, pardon the typo. Make that foreign bureau cats.

It’s become a tradition of sorts at The New York Times: far-flung foreign correspondents who populate their sometimes isolated outposts — from Kabul and Baghdad to Cairo and Dakar, in bureaus that often consist of only one or two journalists and occasionally their families — with local feline companions.

Michael Slackman, The Times’s international editor, took on two Egyptian strays during a five-year stint as bureau chief in Cairo: Yodarella and Spunky. (“Spunky,” he said, “is my soul mate.”)

Jack Healy, a correspondent in Baghdad from 2010 to 2012, repatriated to a post in Denver with an Iraqi feral, Malicki, in tow.

And Walt Baranger, who circled the globe many times over as a news technology editor for The Times, returned from helping establish a bureau in Kabul in 2001 with a stray named Purdah.

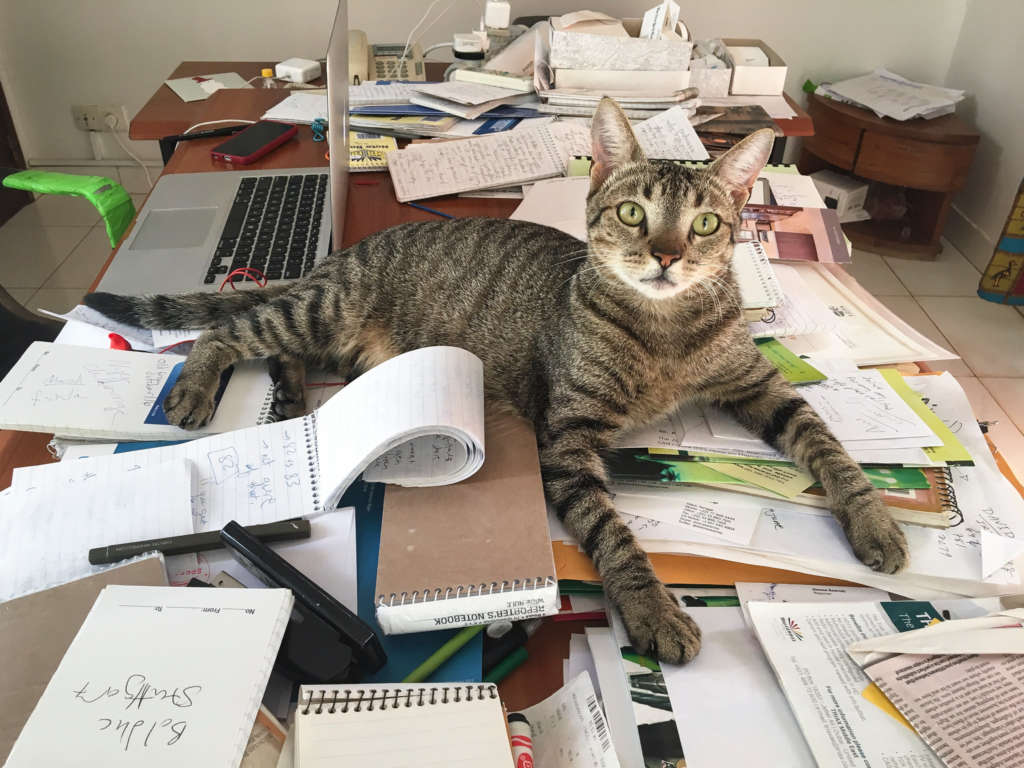

To date, Dionne Searcey, the West Africa bureau chief, has adopted two cats: Muus (which means “cat” in Wolof, the lingua franca in Senegal) and Spotty/Dotty. (In case you’re wondering, the slash is voiced — as in, “Spotty Slash Dotty.”)

Muus spends his days roaming the top of the walls that enclose the bureau, gingerly navigating the broken glass, set into mortar, that’s meant to deter would-be intruders.

Spotty/Dotty, on the other hand, has a penchant for sprawling across laps and desks.

“Mostly they’re here to help our three kids feel comfortable,” said Ms. Searcey, who described the streets in Dakar as littered with strays.

But adopting the cats has also, in part, been a response to a nagging sense of powerlessness, she said. “At least I can make one little difference for a street cat.”

“For me, it was an emotional crutch,” Mr. Healy said, noting that the Baghdad bureau had a large assortment of yowly street cats.

“There’s just something about coming across an affectionate animal, wherever you are. And I think that’s heightened when you’re in an unfamiliar environment.”

“Plus, you can’t pet your colleagues.”

Mr. Baranger, who retired in late 2016 after 27 years at The Times, witnessed the bureau cat phenomenon in several countries.

“Usually what happened was: You got strays, and if you feed them once, that’s it.”

The golden age of “the cat thing,” as Mr. Baranger calls it, started with Jane Scott-Long and her husband, John Burns. Sent to India in the 1990s, the couple began adopting cats and dogs en masse; they eventually went through the trouble of sending some of the animals back to their home country of England and, later, to foster families in the United States.

“After 9/11, we built up the bureau in Islamabad, and John and Jane moved in,” Mr. Baranger said. “And Islamabad has a whole bunch of strays living in the woods — so, naturally, Jane took to feeding them.”

Ms. Scott-Long, who was the bureau manager in Islamabad, Kabul and Baghdad, carried on the cat tradition in Baghdad when The Times established the bureau in 2003. There, the compound was home to as many as 60 cats at a time, later prompting Mr. Burns to write an essay for the Week in Review titled “What Cats Know About War.”

“As The Times’s bureau chief, part of my routine was to ask, each night, how many cats we had seated for dinner,” he wrote. “In a place where we could do little else to relieve the war’s miseries, the tally became a measure of one small thing we could do to favor life over death.”

Mr. Baranger remembers it all too well. “At that point, in Baghdad, there were bombs going off several times a day, sometimes killing dozens of people at time,” he explained. “The cats were a catharsis. You were able to take care of them. You knew you were making a difference.”

“And it took your mind off the war for a while,” he said.

Of course, falling for a local cat’s charms, in situ, is one thing. Carrying a cat thousands of miles home, at the end of one’s foreign posting, is something else entirely.

But foreign correspondents often feel they have no choice — despite the fact that the return trip is rarely easy, for the cats or their owners.

Mr. Healy’s westward transit was particularly traumatic. After spending hours obtaining what amounted to “an Iraqi exit visa for cats,” he was mercilessly clawed and bitten when officials insisted that he remove Malicki from her cage at a security check. He eventually checked into a Denver emergency room and was given an IV.

“My hands were completely destroyed: puncture wounds, bites,” he said.

But Malicki has since settled into her Rocky Mountain lifestyle with aplomb — though “she’s still the same gluttonous beast she was back in Iraq,” Mr. Healy said.

Adam Nossiter, a Paris-based correspondent who preceded Ms. Searcey as West Africa chief, also made off with his bureau cat.

“It’s been a difficult transition for him,” said Mr. Nossiter, referring to Louis, a stray African cat he adopted during his stint in Dakar. (Louis is named after Saint-Louis, the Senegalese city.)

“He’s used to spending his days outside: chasing lizards, climbing the mango tree. Now he lives in an apartment in the First Arrondissement, in the heart of the fashion district.”

“He can go out on the balcony and observe the Chanel workshop across the street,” he added with a laugh, “but it’s not quite the same thing.”

As for opting to bring Louis along when he and his family departed from Senegal, there was never any question.

“I’m extremely fond of him,” Mr. Nossiter said, “and he’s an indispensable part of the household.”

“And the kids would have revolted, anyway.”

The New York Times