Even during Kell Brook’s desperate final stand against Gennady Golovkin on Saturday night, when it was clear his reddened body was spent and staggering backwards, he was able to perform one last trick. For despite struggling to paw or claw meekly at his opponent, he somehow retained enough rugged bloody-mindedness to stay upright as howitzers rattled into his skin and shattered bone.

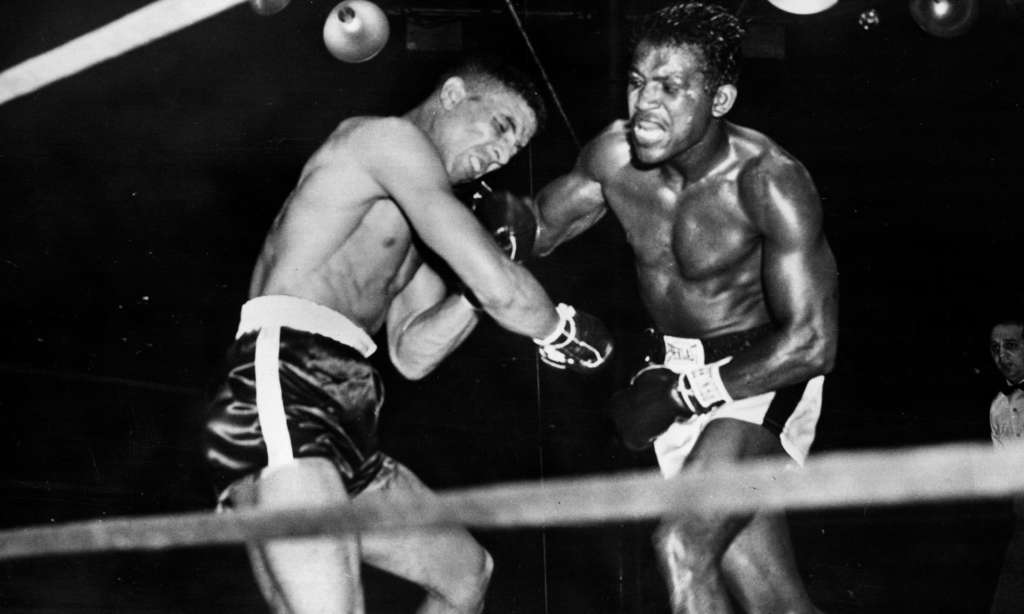

His defiance brought to mind the American essayist AJ Liebling’s description of the final moments of Randolph Turpin’s defeat by Sugar Ray Robinson, in their world middleweight title rematch exactly 65 years ago today. As Turpin took a “succession of smashing hits such as I had never seen a fighter take without falling down”, Liebling gazed into his “sad face … a face of a schoolboy who has long trained himself not to cry under punishment, and who has had endless chances to practice”. His words retain a universal truth, even generations on.

I have been thinking about Turpin recently and not only because of the anniversary of his rematch with Robinson. Last week some suggested that, if Brook were to shock Golovkin, it would eclipse their first fight, 64 days earlier when, on a wild night in Earl’s Court, Turpin beat the greatest pound-for-pound boxer of them all – comments that jarred given Robinson had lost once in 132 fights at the time. It also struck me that Turpin, like most historical figures, has been reduced to a one or two fact crib note – when he deserves more recognition as one of boxing’s ultimate rags to riches to rags stories.

He was born into poverty in Leamington Spa. Then his father, who was British Guyanese, died when he was barely 12 months old, forcing his white mother to raise him alone – a situation that was made even harder given he was one of the few black faces in the town in 1920s England.

Yet Turpin’s athletic gifts – he was so talented he was banned from competing in his school’s sports day – provided a route out of poverty. Dick, the older of his two elder brothers, became the first black fighter to win a title under British Board of Control rules but Randolph was even better, blasting his way through domestic and European opposition before dominating Robinson over 15 rounds to become world champion at 23. At the time the US radio commentator Stan Lomax hailed it as boxing’s biggest upset since Jack Dempsey lost his heavyweight title to Gene Tunney 25 years earlier.

At a civic reception afterwards a jet fighter performed loops over the town hall and 20,000 turned up to sing “For he’s a jolly good fellow”. Yet a series of familiar vices, including Casanova-scale womanizing and increasing ill-discipline, ensured Turpin never hit those heights again. And while he was still good enough to add the British and Empire light-heavyweight title to his résumé, another world title was to elude him after he barely trained for a fight with Bobo Olson and lost a winnable fight on points. As the New York Post writer Jimmy Cannon put it: “It was as though Turpin thought the ropes were a perpendicular hammock where he might loll in brief tranquility. Consequently he would rest against them, his aching head straining backwards on the cords of his neck as though he were trying to locate an invisible pillow.” Outside the ring Turpin’s life became more turbulent. He admitted slapping his first wife “three or four times” because she had shouted at him. He faced trial for rape and assault in Harlem – a settlement was reached – and despite winning £300,000 during his career he ended up broke and owing the taxman thousands. He ended up committing suicide at 37, having written a parting note in front of his wife and kids that morning. His doctor suspected he had brain damage from fighting.

But make no mistake, he could fight. My grandfather, Jimmy Ingle, had first-hand experience of Turpin’s power. He was good enough to be the first Irishman to become European amateur champion at the age of 17, after which he sparred with the three-weight world champion Henry Armstrong and was approached by Tunney to manage him in America. He was good enough, too, to hold the British welterweight and middleweight champion Ernie Roderick to a draw.

Facing Turpin, in front of 10,000 people in Coventry, was a different matter. “The fight lasted three rounds,” he later wrote. “Afterwards I could only recall the first minute. A right-hand punch exploded on my chin and for the remainder of the bout I boxed only from instinct. Later my trainer told me I was down for three counts of nine in every round and that the referee had stopped it at the end of round three. He was a ghost with a hammer.”

Something else struck me re-reading Liebling’s classic work, The Sweet Science: the description of Turpin’s power punches, fired in “always at some curious angle”. As he put it: “One punch for the body looked like a man releasing a bowling ball; another a right-hand for the head, was like a granny boxing a boy’s ears. He might be one of the hardest hitters in history. Turpin was so strong that his unconventional blows shook Robinson when they landed, although Robinson knew that, according to the book, they shouldn’t.”

He was referring to the fighter once known as the Leamington Licker but his words eerily describe Golovkin’s stun-gun fists, spraying punches from all angles, sending his opponents – and everyone watching – dizzy.

(The Guardian)