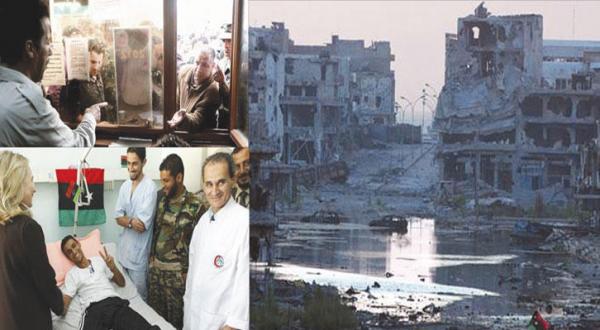

Destruction in Benghazi, Libya, last July after fighting between pro-government forces and an alliance of former anti-Qaddafi rebels linked to the extremist group Ansar al-Sharia

Washington- The fall of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi seemed to vindicate Hillary Clinton since after his fall, militias refused to disarm, neighbors fanned a civil war, and ISIS found refuge.

The US is considering another intervention in Libya, yet this time to fight ISIS; but the question remains whether a military solution is possible in this case.

The current chaos in Libya is certainly due to the military intervention in the country. Back then, Clinton found herself surrounded by British, French, and other doubters.

The military intervention marked a horrible start to the new era for Libya. The dictator was dragged from the sewer pipe where he was hiding, tossed around by furious rebel soldiers, beaten and stabbed.

A cellphone video showed the pocked face of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, “the Leader” who had terrified Libyans for four decades, looking frightened and bewildered, knowing he will soon be dead.

The first news reports of Colonel Qaddafi’s capture and killing in October 2011 reached the US Secretary of State in Kabul, Afghanistan, where she had just sat for a televised interview. “Wow!” she said, looking at an aide’s BlackBerry before cautiously noting that the report had not yet been confirmed. Nonetheless, Hillary Clinton seemed impatient for a conclusion to the multinational military intervention she had done so much to organize, and in a rare unguarded moment, she dropped her reserve and exclaimed: “We came, we saw, he died!”

Two days earlier, Mrs. Clinton had taken a triumphal tour in the Libyan capital, Tripoli, and for weeks top aides had been circulating data describing her starring role in the events that had led to this moment.

In one of the memos, her top policy aide, Jake Sullivan, wrote, demonstrating Mrs. Clinton’s “leadership, US political orientation toward Libya from the beginning till the end.” The memo’s language put her at the center of everything: “HRC announces … HRC directs … HRC travels … HRC engages,” it read.

It was a brag sheet for a cabinet member with presidential goals and the Clinton team’s eagerness to claim credit for her prompted eye-rolling at the White House and the Pentagon. Some couldn’t prevent themselves from laughing after hearing her aides saying that she had practically called in the airstrikes in Libya herself.

However, there were plenty of signs that the triumph won’t last long and that the vacuum left by Colonel Qaddafi’s death will provoke violence acts and divisions.

In fact, on the same day that Mr. Sullivan compiled his laudatory memo in August, the US Under-Secretary General for Middle East Political Affairs, Jeffrey D. Feltman, had sent a lengthy email with an utterly different tone about what he had seen on his own visit to Libya.

The country’s interim leaders seemed shockingly disengaged, he wrote, indicating that Mahmoud Jibril, the acting Prime Minister, who had helped persuade Mrs. Clinton to back the opposition, was commuting from Qatar, making only “cameo” appearances in Libya.

In addition, a leading rebel general had been assassinated, underscoring the hazard of “revenge killings.” Islamists were moving aggressively to seize power and members of the anti-Qaddafi coalition were financing them.

Mr. Feltman reported an alarming lassitude regarding a task of utmost urgency, which was disarming the militia fighters who had dethroned the dictator but now threatened the nation’s unity. Mr. Jibril and his associates, he wrote, “tried to disregard the problem that militias could pose on Libya after Qaddafi’s era.”

In short, the well-intentioned men nominally running Libya were relying on “luck, tribal discipline and the ‘gentle character’ of the Libyan people” for a peaceful future. “We will continue to push on this,” he wrote.

In the ensuing months, Mr. Feltman’s memo proved hauntingly prescient. But Libya’s Western allies, preoccupied by domestic politics and the crisis in Syria, soon relegated the country to the back burner.

On the other hand, Mrs. Clinton would be mostly a bystander as the country dissolved into chaos, leading to a civil war that destabilized the region, provoking

the refugee crisis in Europe and allowing ISIS to establish a Libyan haven that the United States is now desperately trying to contain.

“Nobody will say it’s too late. No one wants to say it,” said Mahmud Shammam, who served as chief spokesman for the interim government. “But I’m afraid there is very little time left for Libya,” he added.

Media reports referred to Mrs. Clinton’s one brief visit to Libya in October 2011 as a “victory lap,” but the declaration was definitely premature.

During her visit, security precautions were extraordinary, with ships positioned off the coast in case an emergency evacuation was needed. As it turned out, there was no violence, but the wild celebratory scenes in the Libyan capital that day actually highlighted the divisions in the new order.

“I am proud to stand here on the soil of a free Libya,” she declared, standing alongside Mr. Jibril. “It is a great privilege to see a new future for Libya being born. No doubt the work ahead is quite challenging, but the Libyan people have demonstrated the resolve and resilience necessary to achieve their goals.”

Yet everywhere Mrs. Clinton went; there was the other face of the rebellion. Crowds of Kalashnikov-toting fighters, or revolutionaries, as they called themselves, mobbed her motorcade and pushed to glimpse the American celebrity. Mostly they cheered, and Mrs. Clinton remained poised, but her security guards watched the uproar with much concern.

Mrs. Clinton certainly understood how hard the transition to a post-Qaddafi Libya would be. In February, before the allied bombing began, she noted that political change in Egypt had proved tumultuous despite strong institutions.

“So imagine how difficult it will be in a country like Libya,” she said. “Qaddafi ruled for 42 years by basically destroying all institutions and never even creating an army, so that it could not be used against him.”

Earlier, the President’s National Security Adviser, Tom Donilon, had created a planning group called “Post-Qaddafi.”

Mrs. Clinton helped organize the Libya Contact Group, a powerhouse collection of countries that had pledged to work for a stable and prosperous future. By early 2012, she had flown to a dozen international meetings on Libya, part of a grueling

schedule of official travel in which she kept competitive track of miles traveled and countries visited.

For his part, Dennis B. Ross, a veteran Middle East expert at the National Security Council, argued unsuccessfully for an outside peacekeeping force; but with oil beginning to flow again from Libyan wells, he was pleasantly surprised by how things seemed to be going.

“I had unease that there wasn’t more being done more quickly to create cohesive security forces,” Mr. Ross said. “But the last six months of 2011, carried a fair amount of optimism.”