Washington-Since her return from San Francisco in 2009, Khulood had been marooned in Jordan. By 2014, she was living in a small apartment in a working-class neighborhood of eastern Amman with her father and two sisters, Teamim and Sahar. It was a dreary place, a three-story walk-up overlooking a dusty commercial road, but it was softened by the presence of Mystery, the sisters’ pet cat, and Shiny, a small box turtle they rescued from the street.

Before leaving for the United States in 2008 Khulood had briefly worked for a Japanese humanitarian organization called Kokkyo naki Kodomotachi (Children Without Borders), or KnK, and she rejoined the agency upon her return to Amman the following year. Her principal task was to help acclimate some of the countless thousands of Iraqi children whose families had fled to Jordan to escape the war, and so impressed were the KnK supervisors with Khulood’s connection to the children that they soon hired her two sisters as well. Around the same time, Ali al-Zaidi, the retired radiologist and patriarch of the family, found work on the loading docks of a yogurt factory on the industrial outskirts of Amman. In 2014, the family was at least scraping by.

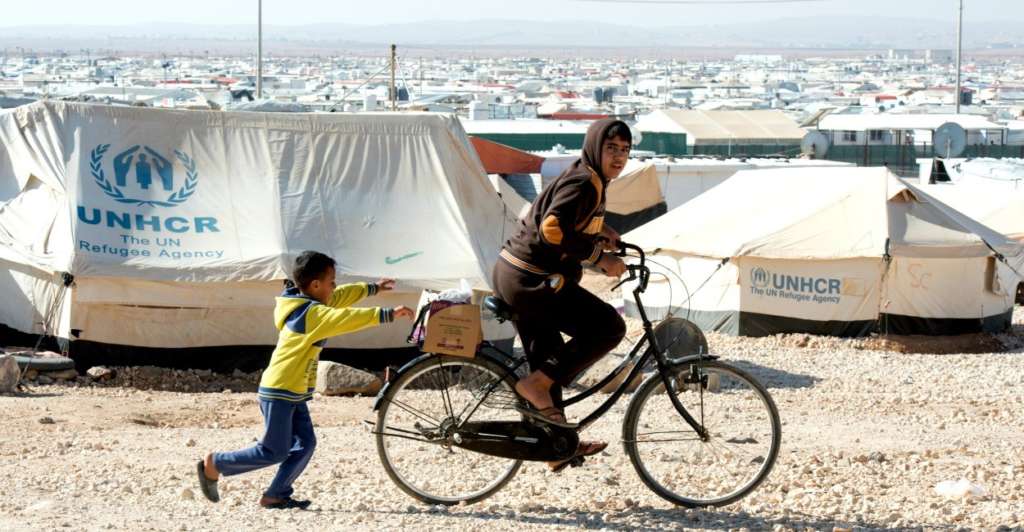

Khulood’s work at KnK had undergone a shift, though. With the war in Iraq having abated, the number of Iraqi refugees in Jordan was drastically reduced from its half-million peak. They were soon replaced, however, by new refugees from the war in Syria — just a trickle at first, but by the end of 2014, their number was more than 600,000.

In certain ways, Khulood found the Syrian children quite different from their Iraqi counterparts. “The Iraqis, because they had become so tired of war, they were very peaceful and easy to work with,” she said. “But the Syrian children — the boys — they have this idea, ‘We have to go back to Syria to fight.’ They hear this constantly from their fathers — ‘You’re going to be a soldier and go back to Syria’ — so they’re like little rebels, not little kids. It’s all about home, missing home, how they need to go back and avenge what happened.” By contrast, the girls had far more in common. “In both Iraq and Syria, girls are taught to keep everything inside. They aren’t listened to. This makes it much harder to reach them, so their problems are deeper.”

Khulood still hadn’t given up on her quest to get her family out of the region. For several years, she continued to petition for the United States to reopen their case, but those efforts went nowhere. By 2014, she was holding out special hope for Britain; in Jordan, she had worked as an interpreter for a British film company, and with letters of support from her former co-workers, Khulood reasoned, the authorities there might look favorably on her. She had recently become aware of a rather diabolical Catch-22, however. Nearly the only way to win asylum in Britain — or in any other country, for that matter — was to present the petition in person. To do that, Khulood first needed to obtain a British visa, and to get that, she needed to have legal residency in Jordan. “And that’s impossible,” she said. “Jordan only gives residency to wealthy refugees who, of course, have no problem resettling in Europe anyway.”

Still, in April 2014, Khulood hadn’t completely given up hope. Possessed of a seemingly unconquerable will, over several days of conversation, she seemed determined to put the very best face on her situation, and she was far more interested in talking up her current plans than her past failures. Only once did this brave facade crack, and it came amid a discussion about the future she imagined for the refugee children she worked with.

“I stay with this because I want these kids to have a better life than me,” she said, “but frankly, I think their lives will be wasted just like mine. I try not to think that way, but, really, let’s be candid: This is their future. For me, these past nine years have been wasted. My sisters and I, we have dreams. We are educated, we want to study, to have careers. But in Jordan we cannot legally work, and we cannot leave, so we are just standing in place. That’s all. Now we’re becoming old, we’re all in our 30s, but still we can’t marry or start families, because then we will never get out of here.”

Khulood sat back and let out a dispirited sigh. “I’m sorry. I try to never pity myself or to blame anyone for this situation, but I really wish the Americans had thought more about what they were doing before they came to Iraq. That’s what started all this. Without that, we would be normal.”

But for Khulood and her sisters, the situation was about to grow even worse. In the autumn of 2014, Khulood said, KnK was having problems with the Jordanian government, which insisted that the organization’s foreign staff members have legal work permits. While KnK said the sisters’ work was exemplary, its efforts to keep them were in vain; that December, all three Zaidi sisters were dismissed from their jobs on the same day.

Egypt

On Oct. 27, 2014, Laila Soueif and her oldest daughter, Mona, climbed the short row of steps leading to the main entrance of the Egyptian Supreme Court building, then stopped and sat beside one of its stone columns. From her backpack, Laila drew out a small sign written on cardboard. It announced she and her daughter were going to intensify the partial hunger strike they began in September to protest the injustices committed against their family. They would remain there off and on for the next 48 hours, taking no food or liquids.

“The idea wasn’t to kill ourselves,” Laila explained, “but to draw attention to what the Sisi regime was doing. It was the only weapon we had left.” As for its efficacy, she was matter-of-fact. “A few people passing signaled that they supported us — sometimes quite a subtle signal.”

Adding another layer of pain to the experience, it came at a time when Laila’s family had, quite literally, disappeared before her eyes.

The first sign that the Sisi regime was to take a much dimmer view than its predecessors of dissent to its rule came with Alaa’s arrest in late November 2013. Rather than being released on bail to await trial, he and his 24 co-defendants were held for the next four months. In a tactic apparently designed to break his will, Alaa’s release on bail in March 2014 was followed by his rearrest three months later.

If average Egyptians were alarmed by the deepening repression in their country — less than a year after Sisi took power, there were already far more political prisoners in Egypt’s jails than there had ever been under Mubarak — they gave scant evidence of it. In presidential elections that May, Sisi, now officially retired from the military, won with more than 96 percent of the vote. While this surely wasn’t a wholly accurate reflection of his popularity — between those political parties that had been banned and those that boycotted the election, Sisi faced only token opposition — even an ardent opponent like Laila Soueif recognized that the former general had widespread support. She had even seen it among many of her friends and university co-workers. “They had this idea that, ‘O.K., maybe he’s a little rough, but he saved us from the Islamists,’ ” she said. “That’s all they cared about, all they saw.”

Up to that point, Laila’s youngest daughter, Sanaa, then 20, had avoided the family tradition of run-ins with the law. On June 21, 2014, that changed. Increasingly infuriated by the treatment of her brother and Egypt’s other political prisoners, Sanaa joined a human rights rally in Cairo. Within minutes, she was arrested on the same charge as her brother: violating the protest law.

Even under the tightening Sisi regime, members of the Cairene upper class like Sanaa enjoyed a degree of immunity — the main enemies of the state, after all, were the working-class followers of the Muslim Brotherhood, and they were to be ruthlessly hunted down. But when brought before a magistrate, the college student took a bold step. Despite suggestions from the judge that she stay quiet, Sanaa insisted that she had been a chief organizer of the demonstration and refused to sign her statement until this detail was included. “She wasn’t going to let them do the usual thing of letting the high-profile activists go and pound on the lesser-known ones,” Laila said. Sanaa, like her older brother, was held in jail pending trial.

For Ahmed Seif, Egypt’s pre-eminent human rights lawyer, it had meant that his ever-expanding roster of clients now included two of his own children. At a news conference the previous January, the former political prisoner took the microphone to eloquently address his imprisoned son, Alaa. “I wanted you to inherit a democratic society that guards your rights, my son, but instead I passed on the prison cell that held me, and now holds you.” By June, that haunting message applied equally to his youngest daughter.

Soon, matters took an even grimmer turn for the family of Laila Soueif. Long in frail health, Ahmed had been scheduled for open-heart surgery at the end of August; on the 16th of that month, he suddenly collapsed and then fell into a coma. Only after intense lobbying by both influential Egyptians and international human rights organizations did the Sisi regime grant Alaa and Sanaa afternoon furloughs to visit their father before he died.

“And that was the absolute worst day,” Laila said, “maybe the worst day of my life. Sanaa was being held in a police station, so we had been able to see her and tell her what was going on, but Alaa had no idea. He showed up at the hospital with flowers for Ahmed, so I had to take him aside to say his father was in a coma. He said, ‘So he won’t even know I’m here then’ and just threw the flowers out.”

The day after that hospital visit, Alaa went on a hunger strike in his cell. Sanaa stopped eating also, on Aug. 28, the day of her father’s funeral. A week later, Laila and Mona announced their partial hunger strike, in which they would take only anti-dehydration liquids.

In light of both Ahmed’s death and the family’s prominence, many observers believed that Alaa and Sanaa would be shown leniency by the courts. That belief was misplaced. On Oct. 26, 2014, Sanaa was sentenced to three years in prison for violating the protest law. The next day, Laila and Mona took to the courthouse steps for their intensified hunger strike. Laila braced herself for more bad news when Alaa went to trial the following month, by remembering something her husband had said.

“Because Ahmed had spent so much time in courtrooms and knew what certain things meant,” she said, “he was always very accurate in his predictions. Before he died, when he was still representing Alaa, he told me, ‘Prepare yourself, because they’re going to give him five years.’ ”

Syria

By the time Laila had begun her hunger strike and Khulood and her sisters were losing their jobs and Majdi el-Mangoush was back in school, Majd Ibrahim had himself found a moment of respite — one that, although brief, had been a long time coming.

With the serial siege of Homs steadily grinding ever more of the city’s neighborhoods to dust, by early 2014 even the Ibrahim family’s shelter home was no longer safe. That March, the family moved once again, this time to New Akrama, a neighborhood that had been spared the worst of the violence. There, they simply waited along with everyone else for something, anything, to change.

That change finally came in May, when the last of Homs’ rebels accepted a brokered cease-fire and safe passage from the city. The three-year siege of Homs was over. What had once been a thriving, cosmopolitan city was now known as Syria’s Stalingrad, with vast expanses of its neighborhoods uninhabitable. It was also only then that the full horror of what some of its residents had been subjected to came to light. In the total-war environment, some residents had starved to death, while others had survived by eating leaves and weeds.

But even if a kind of peace had reached the shattered streets of Homs, the war continued elsewhere in Syria, and in a form that boded poorly for all its citizens. Majd Ibrahim heard the names of so many new militias competing with the plethora of already existing ones, it was quite impossible to keep track of them all. For sheer daring and cruelty, however, one group stood out: ISIS.

An even more radical offshoot of Al Qaeda, the newcomers attracted Islamic extremists from around the world. In Syria, the group announced its presence with a series of sudden, brutal attacks in Aleppo and the desert towns to the east, battling not just the Syrian Army but also those rival militias it deemed “apostate.” What most drew the attention of Majd Ibrahim was the group’s reputation for complete mercilessness, for eliminating by the most horrific means possible any who would resist its will.

Just a month after the Homs siege ended, most of the rest of the world would hear of ISIS, too, when it stormed out of the Syrian desert to utterly transform the Middle Eastern battlefield yet again.

The New York Times Magazine