The New York Time Magazine has issued an epic report that tells the story of the catastrophe that has fractured the Arab world since the invasion of Iraq 13 years ago, leading to the rise of ISIS and the global refugee crisis. The geography of this catastrophe is broad and its causes are many, but its consequences — war and uncertainty throughout the world — are familiar to us all. Scott Anderson’s story gives the reader a visceral sense of how it all unfolded, through the eyes of six characters in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Iraq and Iraqi Kurdistan.

Accompanying Anderson’s text are 10 portfolios by the photographer Paolo Pellegrin, drawn from his extensive travels across the region over the last 14 years, as well as a landmark virtual-reality experience that embeds the viewer with the Iraqi fighting forces during the battle to retake Falluja.

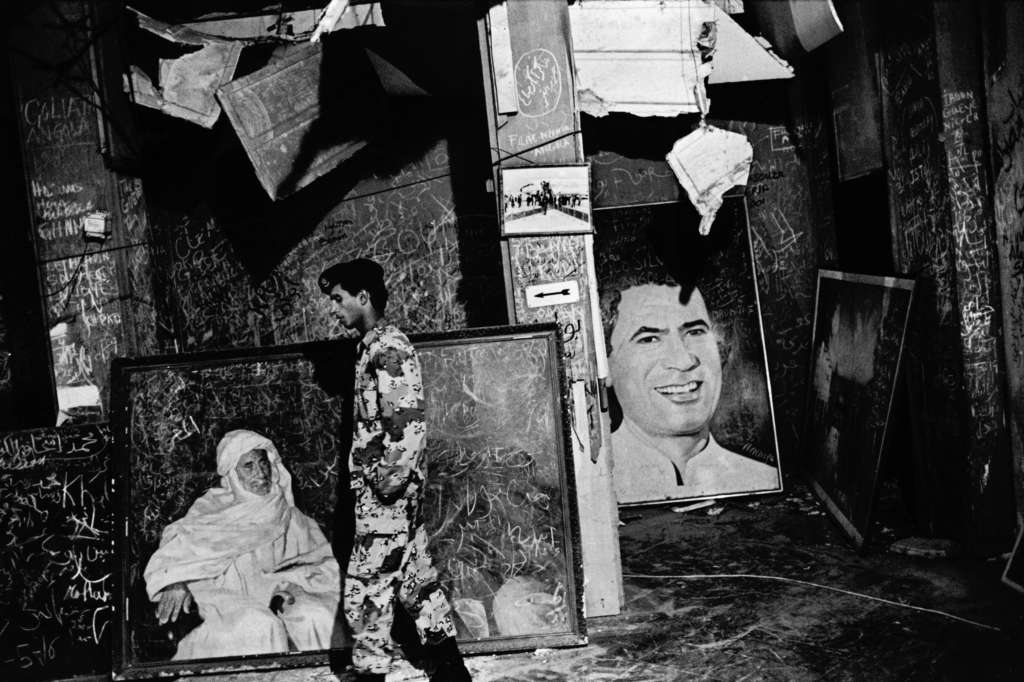

Anderson depicted the situation in Libya today through activist Majdi el-Mangoush from the Libyan city of Misurata, where the revolution that ousted former President Muammar el-Qaddafi had first sparked.

Anderson wrote: The confines of the Tripoli high school were a good deal more porous than those of the air force academy, and from their minders the cadets gradually learned something of the conflict that had befallen their nation. Although the unrest was fomented by criminal gangs and foreign mercenaries in the hire of Libya’s Western enemies, they were told, misguided segments of the population had joined in to spread it. By the beginning of March, this foreign-spawned criminality was most intense in Misurata and Benghazi, and both cities had become pitched battlegrounds.

Provided with this narrative, Majdi was not altogether surprised when, in mid-March, Western alliance warplanes began appearing over Tripoli to bomb government installations. It seemed merely to confirm that the nation was being attacked from beyond. Naturally, the situation also caused both Majdi and Jalal to worry about the fate of their hometowns and wonder which of their friends might have been seduced into joining the traitors’ ranks. “That’s something we talked about a lot,” Majdi said. “ ‘Oh, Khalid was always a little crazy; I bet he’s gone with them.’ ”

The cadets seemed gradually to win the trust of the regime, enough for one large group to be transferred to a military base in mid-April to begin training on missile-guidance systems. Neither Majdi nor Jalal were selected for this mission, however, and their stay at the high school dragged on. Then one day in early May, Majdi ran into an old acquaintance at the barracks. The acquaintance, Mohammed, was now a military intelligence officer. He wanted to talk to Majdi about Misurata. The two chatted for some time, with Mohammed asking about different locations in the city and if the young cadet might know who the town’s “civic leaders” were. Majdi thought nothing of the conversation, but one afternoon a few days later, he was called to headquarters.

There, an officer informed Majdi that he had been selected to join the cadets undergoing missile-guidance training; the jeep that would transport him to the base was leaving immediately. So hurried was his departure that Majdi didn’t even have time to say goodbye to Jalal.

But the jeep driver didn’t take him to the army base. Instead, he followed the Tripoli ring road to the coastal highway and then turned east.

By early evening, they had reached Ad Dafiniyah, the last town before Misurata and the farthest limits of government control. There, Majdi was led into a small farmhouse, where he was told someone wanted to speak to him on the phone. It was Mohammed, the military intelligence officer.

As Mohammed explained, the young air force cadet had been chosen for a “special patriotic mission”: He was to slip into Misurata and find out who the rebel leaders were and where they lived. Once he had done this, he would pass the information to a liaison officer secreted within Misurata, a man named Ayoub. To make contact with Ayoub, Majdi was given a Thuraya satellite phone and a number to call.

Upon hearing all this, Majdi had two thoughts. One was about his friends at home: Ever since hearing about the scale of fighting in Misurata, he assumed that some of his friends must have joined the other side. If he carried out this mission, it might very well result in their deaths.

The other thought was of a recent conversation he had with Jalal. His friend had awoken in a despondent state of mind, explaining that he’d had a terrible dream, and it took Majdi some time to coax out the details. “I dreamt that you and I were sent to fight in Misurata,” Jalal finally revealed, “and that you were killed.”

But any hesitation swiftly passed. In his goldfish-bowl existence in Tripoli, Majdi had heard only what the regime wanted him to hear, and if he didn’t believe all of it, he believed enough of it to want to help defeat the foreigners and their followers who were destroying Libya, even if this included people he knew. Perhaps most of all, he just wanted the limbo to end. For nearly three months, he had been cut off from both his family and the outside world, and he simply wanted something — anything — to happen. So he agreed.

Early the next morning, Majdi said goodbye to his companions at the farmhouse and headed alone into no man’s land. Misurata lay some 10 miles to the east. In the right front pocket of his pants he carried his military identification card. If stopped by the rebels, this card in itself was unlikely to cause him problems; countless government soldiers had deserted, and the fact that Majdi was from Misurata would certainly lend credence to his explanation that he was trying only to go home. The satellite phone in his left pocket was a very different matter, though. With the severing of internet and cellphone reception, the Thuraya had become the standard mode of communication for regime operatives in the field, and if the rebels discovered Majdi’s — sure to be found in the most cursory of searches — they would inevitably conclude that he was coming into Misurata as a spy. Under those circumstances, summary execution was probably the most merciful outcome he could hope for.

As he walked, the sound of gunfire grew in intensity, and there was the occasional rumble of distant artillery explosions. But between the light wind and the rolling-hill topography of the Misurata coastal shelf, it was quite impossible for Majdi to determine how close any of it was or even its direction. He tried to bear in mind something he picked up in basic training, that the most worrisome noise on a battlefield wasn’t gunshots but rather a soft popping sound, like the snapping of fingers. This was the sound the air made as it rejoined behind a bullet, and you heard it only when a bullet passed close to your head.

Majdi’s memory of that journey is vague. He doesn’t remember how long it took; he estimates that he walked for about three hours, but it could have been shorter or twice as long. Only one moment sticks out in his mind. About halfway across no man’s land, Majdi was suddenly filled with a sense of joy unlike anything he had ever experienced before.

“I can’t really describe it,” he said, “and I’ve never had a feeling like it since, but I was just so happy, so completely at peace with everything.” He fell silent for a time, groping for an explanation. “I think it’s because I was in the one place where I was out from the shadow of others. I hadn’t betrayed my friends yet, I hadn’t betrayed my country yet — that is what lay ahead — so as long as I stayed out there, I was free.”

Like Majdi el-Mangoush in Libya, Majd Ibrahim was at first merely a long-distance observer of the deepening turmoil in the region. The Syrian dictatorship made no attempt to conceal the revolts in Tunisia and Egypt from its people, and indeed spoke of them openly, with a certain smugness. “We have more difficult circumstances than most of the Arab countries,” President Bashar al-Assad grandly informed The Wall Street Journal on Jan. 31, “but in spite of that, Syria is stable. Why? Because you have to be very closely linked to the beliefs of the people.”

Shortly after that interview, however, Syria’s state-controlled media went silent on the whole topic. Certainly there was scant mention when, in early March, demonstrators took to the streets of the southern Syrian city Dara’a to protest the arrest and reported torture of a group of high-school students for writing anti-government graffiti on walls. “I heard about what happened in Dara’a through social media,” Majd said, “from Facebook and YouTube.”

It was from the same venues that Majd learned of a solidarity protest, called the Day of Dignity, that was to take place in front of the Khaled bin al-Waleed Mosque in downtown Homs on March 18. Heeding the admonitions of his parents, Majd stayed well away from that rally, but he heard through friends that hundreds of demonstrators had shown up, watched over by a nearly equal number of police officers and state security personnel. It was a shocking story to the 18-year-old college student; Homs had simply never experienced anything like it.

And that demonstration was tiny in comparison with the next, held a week later. This time, the protesters numbered in the thousands. Majd, figuring there was safety in numbers amid the throngs of onlookers, managed to get close enough to hear their demands: for political reform, greater civil rights, a repeal of the state-of-emergency edict that had been in place in Syria for the previous 48 years.

On March 30, Assad delivered a speech to the Syrian Parliament, carried live by state television and radio outlets. While protests had spread to a number of Syrian cities, they were still largely peaceful, with dissenters calling for changes in the regime rather than for its overthrow. As a result — and with the assumption that the regime had learned something from the recent collapse of the Tunisian and Egyptian governments and the widening chaos in Libya — many expected Assad to take a conciliatory approach.

That expectation was also based on Assad’s personality. In the 11 years he had ruled the nation since the death of his father, the unassuming ophthalmologist had adopted many trappings of reform. With his attractive young wife, the British-born Asma, he had put a pleasing, modern face on the Syrian autocracy. Behind the charm offensive, however, little had truly changed; Syria’s secret police were still everywhere, and the “deep state” — the country’s permanent ruling class of bureaucrats and military figures — remained firmly in the hands of the Alawite minority. The Alawites, along with many in Syria’s Christian minority, feared that any compromise with the protesters was to invite a Sunni revolution and, with it, their demise.

After offering vague palliatives about future reform, Assad instead used his parliamentary speech to accuse the troublemakers in the streets of aiding the “Israeli enemy” and to issue a stern warning. “Burying sedition is a national, moral and religious duty, and all those who can contribute to burying it and do not are part of it,” he declared. “There is no compromise or middle way in this.” In keeping with a tradition begun during his father’s reign, Assad’s speech was repeatedly interrupted by members of Parliament leaping to their feet to shout out their undying love and gratitude to the president.

In Majd’s memory, a kind of uneasy quiet fell over Homs after Assad’s address. There were still scattered protests about town, watched over by phalanxes of heavily armed security forces, but it was as if no one was quite sure what to do next — each side fearful, perhaps, of leading the nation into the kind of open warfare then roiling Libya.

The interlude ended abruptly on April 17, 2011. That evening, as reported by Al Jazeera, a small group of demonstrators, maybe 40 in all, were protesting outside a mosque in Homs when several cars stopped alongside them. A number of men clambered out of the cars — presumably either local plainclothes police officers or members of the largely Alawite shabiha — and proceeded to shoot at least 25 protesters at point-blank range.

It was as if gasoline had been thrown on a smoldering fire. That night, tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered at Clock Tower Square downtown, and this time, the police and shabiha took to the roofs and upper floors of the surrounding buildings to shoot down at them. “That is when everything changed,” Majd said. “Where before it was protests, from April 17 it was an uprising.”

As protesters started to be killed almost every day, their funerals the next day became rallying points for more protesters to take to the streets; the evermore brutal response of the security forces at these gatherings then created a new round of shaheeds, or martyrs, ensuring greater crowds — and more killing — at the next funerals. By early May, the cycle of violence had escalated so swiftly that the Syrian Army came into Homs en masse, effectively shutting down the city.

“Nobody trusted the local security forces,” Majd recalled, referring to the vast apparatus of mukhabarat and uniformed police who traditionally held sway in Syrian towns. “But everyone liked the soldiers coming in. Even I did, because we believed they had come to protect the people and stop the killing. And it worked. The army had tanks and everything, but they didn’t use them, and very soon the killing ended.”

After just a short time, however, the regime withdrew the bulk of its military forces from Homs in order to deploy them on “pacification” operations elsewhere — and with the army no longer able to provide order, the mukhabarat began distributing heavier weapons to the semiofficial shabiha. The city swiftly fell back into bloodletting. Around Homs, vigilante forces set up roadblocks and conducted raids into neighborhoods now controlled by the rebels. Throughout the summer the fighting continued, with different factions of pro- and anti-regime gunmen taking control of ever more sections of the city.

Then matters took an even more sinister turn. In this most religiously mixed of Syrian cities, suddenly people began turning up dead for no other discernible reason than their religious affiliation. In early November 2011, according to an unconfirmed account from Reuters, gunmen stopped a bus and murdered nine Alawite passengers. The next day, at a nearby roadblock, Syrian security forces, seemingly in retaliation, led 11 Sunni laborers off to be executed. All the while, a terror campaign of kidnappings and assassinations targeted the city’s professional class, leading many of them to go into hiding or flee.

The fighting also had a surreal inconstancy. Some districts saw scorched-earth battle, even as, in others, shops stayed open and the cafes were full. Throughout, Majd Ibrahim continued his hotel-management courses at Al-Baath University. His neighborhood, Waer, remained one of the least affected by the violence, and by carefully monitoring the news for reports of specific conflagrations, he was able on most days to navigate the two-mile journey to his campus. By February 2012, however, the combat had become so indiscriminate that the university announced it was temporarily closing. At the same time, rumors began circulating through Homs that the Syrian Army would be returning in force, this time to put down the rebellion once and for all.

“That’s when my parents decided to send me to Damascus,” Majd explained. “With the university closed and the fighting about to get worse, they felt there was no reason for me to stay — and it was going to become especially dangerous for young men.” When Majd left for the Syrian capital in early February, he passed a seemingly endless line of army transport trucks, tanks and artillery pieces parked on the shoulder of the highway just outside Homs. The next day, the Syrian Army moved in.

The first living soul that Majdi el-Mangoush saw upon reaching Misurata’s western outskirts was a young boy, perhaps 8 or 9, playing in the dirt. The homes all around were deserted and shell-pocked, but then he noticed a car parked in the shadow of a farmhouse wall.

“Is your father here?” Majdi asked the boy. “Will you take me to your father?”

At the farmhouse, he met the boy’s father, a man in his 30s, who was both astonished and deeply suspicious of this stranger emerging from no man’s land. Majdi repeated his cover story: that he had deserted from the regime and was trying to reach his family. He was helped in this subterfuge by his surname, for everyone in Misurata knew of the Mangoush clan. The man’s wariness eased off, and he offered Majdi a lift into town.

As much as he’d heard about the fighting in his hometown, Majdi was unprepared for the reality. Since late February 2011, Misurata had been increasingly under siege by government forces, its residents becoming almost wholly dependent on whatever food and medical supplies could be brought in by sea. All the while, the army had rained down artillery shells, while its soldiers fought the rebels alley by alley, person by person, just as Qaddafi had promised. The siege abated somewhat with the advent of Western alliance airstrikes in late March, but the damage done to the city was staggering. Everywhere Majdi could see buildings blasted by tank shells or scorched by fire, destruction so great that in some places he couldn’t even tell which street or intersection they were passing.

The man from the farmhouse dropped Majdi off at his family’s home. “I just came through the front door,” he recalled. “The first person I saw was my sister. And then there were my sister-in-law and my brother’s children.” At the memory, Majdi blinked back tears. “It had been three months. I thought I would never see them again.”

Majdi spent the rest of that day in reunion with his family. He learned that after his father became seriously ill, his parents had gone out aboard a medical evacuation ship to Tunisia. He also learned that the list of local “traitors” to the regime didn’t just consist of old friends but extended to his own family; in fact, for several weeks, his oldest brother, Mohammed, had secreted a group of deserting air force helicopter pilots in his own home. Everyone, it seemed, had joined the revolution and was now committed, after all Misurata had suffered, to see it through to the finish.

At some point during this family gathering, Majdi briefly excused himself to go to his old bedroom. There, he took the Thuraya from his pocket and hid it on a shelf behind a bundle of bedding. “I didn’t know what I was going to do yet,” he said. “I just knew that I had to hide that phone.”

Over the next week, the returned son of Misurata wandered about his ruined city, meeting up with friends and learning of those who had been wounded or killed in battle. In the process, he came to see that everything he had been told and had believed about the war was a lie. There were no criminals, there were no foreign mercenaries — at least not among the rebels. There were only people like his own family, desperate to throw off dictatorship.

But this realization placed Majdi in a very delicate spot. Ayoub, his intelligence contact, surely knew of his arrival in Misurata and was expecting him to report in. Majdi briefly entertained the idea of simply discarding the Thuraya and going on as if nothing had happened, but then he thought of the repercussions that would befall his family if the regime won out in the end. Or what if the rebels uncovered the regime’s spy cell in the city and his name surfaced?

Faced with these possibilities, the air force cadet came up with a far more clever — and dangerous — plan. In mid-May, he presented himself to the local rebel military council and revealed all. As Majdi well knew, for a would-be spy to throw himself on the mercy of the enemy in wartime is never a good bet — the rebels’ most expedient path would be to imprison or execute him — but against this outcome, he made a bold offer.

The next morning, Majdi finally contacted Ayoub, his regime handler, and agreed to meet two days later in a vacant apartment building downtown. At that meeting, a group of rebel commandos burst in with guns drawn and quickly wrestled both men to the ground. Majdi and Ayoub were then placed in different cars for transport to prison. By the time the rebel military council announced that it had captured “two regime spies” in Misurata, Majdi was already back at his family home.

Although the sting had come off perfectly, there were apt to be other regime operatives aware of Majdi’s assignment, making it risky for him to move about the city. He took advantage of the moment to slip off to Tunisia to visit his parents.

For Majdi, then 24, the contrast of Tunisia — modern, peaceful — was yet another journey into bewilderment. “It was so quiet, so relaxed,” he recalled, “that it took me some time to believe it was real.”

Majdi might easily have stayed on in Tunisia; it’s certainly what his parents wanted. But after a few weeks, he grew restless, gnawed by a sense that his role in his country’s war wasn’t complete. “I think part of it was a kind of revenge. I had been with the army, but they had lied and manipulated me. And, of course, the war wasn’t over yet; people were still fighting and dying. I told my parents I had no choice. I had to go home.”

Back in Misurata, Majdi immediately became active with a local rebel militia, the Dhi Qar Brigade, for the march on Qaddafi’s redoubt in Tripoli. Before he could be deployed there, however, the government forces in the capital collapsed, and the dictator and his remaining loyalists retreated down the coast to Surt, Qaddafi’s tribal homeland district. There, surrounded and with their backs to the sea, they waged a desperate last stand. For a month, Majdi’s unit held a stretch of the Surt bypass highway, shelling regime strongholds and engaging in the occasional firefight whenever the trapped soldiers tried to break out. As elsewhere in the Libyan war — as in most wars, frankly — combat in Surt was an oddly desultory affair, moments of intense action followed by long stretches of tedium, and to Majdi it seemed this rhythm might continue indefinitely.

Instead, it ended very suddenly on Oct. 20, 2011. That morning, a fierce firefight erupted in the western part of Surt, punctuated by a series of airstrikes from Western coalition warplanes; from his perch on the bypass road, Majdi saw enormous plumes of fire and dust rising up from the bombs exploding around the city. Around 2 p.m., there came another concentrated flurry of small-arms fire from the western suburbs, one that lasted about 20 minutes, before all fell quiet. Initially, Majdi and his comrades thought it meant that Qaddafi’s men had surrendered, but there soon came even better news: The dictator himself had been captured and killed. “We all cheered and hugged each other,” Majdi recalled, “because we knew it meant the war was over. After all that killing — and after 42 years of Qaddafi — a new day had finally come to Libya.”

With the fighting at an end, Majdi returned to Misurata and transferred to a militia unit more suited to his gentle character: an ambulance crew ferrying the more severely war-wounded from Misurata’s hospitals to the airport for advanced medical treatment abroad. He greatly enjoyed this work, which he felt showed tangible evidence of recovery after so much death and devastation, and it fortified his optimism about the future.

Then one December day at the Misurata airport, Majdi received a visitor. He was Sameh al-Drisi, the older brother of his friend Jalal, and he had traveled the 500 miles from Benghazi to ask a favor. The Libyan revolution had been over for two months, but the last time anyone in the Drisi family had heard from Jalal was in May. That communication was a short phone call from the Tripoli high school where the air force cadets had been sequestered, and it came just days after Majdi left for his spying mission to Misurata.

Changing course once again, Majdi set out in search of his lost friend with a tenacity that bordered on obsession. Returning to Tripoli, he spent weeks tracking down some of their former academy classmates and, from them, was able to piece together at least part of the mystery. In May 2011, Jalal had been among a group of some 50 cadets at the Tripoli high school who were assembled and told they were being sent to assist front-line troops as they advanced on the rebels in Misurata, checking for old booby-traps and guarding communication and supply lines. Instead, the cadets were used as bait there, sent out over open ground to be shot and shelled at, while the regime’s more seasoned soldiers sat back to observe where the enemy fire was coming from. As one cadet after another fell on this suicide mission, Jalal and two of his comrades managed to reach an outlying farm, where they begged an old farmer to take them south, away from the battlefield; instead, the farmer betrayed the students and delivered them to internal security forces, who in turn delivered them right back to the army. After a round of beatings, the three were sent back to their suicide squad.

But that was as far as the tale went. Shortly after, Jalal’s two companions had made a second escape attempt — this time successfully — but by then Jalal had been moved to a different part of the front.

This set Majdi off on a new search. He finally found another former classmate who completed the story. One day in June, a small group of the cadets — Jalal and others who had managed to survive that long — were bivouacked along a farm road on Misurata’s southern outskirts when an officer drove up and called the students over for a situation report. In that same moment, a missile from an unseen Western alliance warplane or drone blew apart the officer’s car, instantly killing him and most of the cadets standing nearby. When the missile struck, Jalal was sitting beneath a tree some 50 yards away, but it was there that an errant piece of shrapnel found him, tearing off the top of his head. His surviving companions buried Jalal’s spilled brain beneath the tree but put his corpse in a truck with the other dead for transport to some unknown cemetery.

“Of course I was reminded of the dream he’d had,” Majdi said. “Yes, we’d both gone to Misurata to fight, but it was he who died.”

For most people, this might have meant an end to the search, but not Majdi. Recalling the time he had spent with Jalal’s family in Benghazi, the hospitality they had shown him, he was determined to find his friend’s body so that it might be returned to them. After knocking on the doors of countless functionaries in the new revolutionary government, he was finally directed to a Tripoli cemetery where the “traitors” — that is, Qaddafi regime loyalists — had been gathered up and buried.

It was a grim, trash-strewn stretch of land dotted with hundreds of graves. Majdi methodically passed down each row, but Jalal’s name wasn’t listed. Finally, he came to a far corner of the cemetery where he saw a grave marked “unknown.” Majdi felt a burst of excitement, for it occurred to him that given Jalal’s terrible head wound, identification might have been impossible — but then he noticed three more graves with the same “unknown” markers. Returning to the cemetery office, he asked for the photographs taken of the unidentified corpses before burial: The faces of all four were so horribly damaged as to be unrecognizable.

Still, Majdi was now convinced that one of the four was Jalal. He broke the news to the Drisi family and several months later flew to Benghazi to pay his respects to them in person. “It was a very emotional meeting,” he said, “and I apologized to them for not being able to watch out for Jalal, but. …” He drifted off in sadness for a moment, but then abruptly righted himself. “So that is it. Jalal is in one of those four graves, that is for sure.”

(The New York Times Magazine)