Since the eruption of the Arab revolutions that have convulsed the region since 2011, Arab readers seem to have abandoned their bookish pursuits, apparently more concerned with toppling their leaders than spending time immersed in a good book. As a result, sales in the region have declined sharply and markets targeted by publishers have dried up significantly.

Perhaps an indicator of how tough times are, this year Egypt, Syria and Libya have all been absent from the event, joining now-serial absentee Iraq, which has not had a stand here for the last three years. Even Tunisia, the country where the first spark of the Arab Spring was lit, is having a torrid time at this year’s fair, with publishers admitting they have had a “nightmare year,” and that they may not even be able to cover their costs.

It is odd, then, that reports regarding the demise of the Arab-language book are perhaps looking somewhat exaggerated. This is especially surprising if you consider the atmosphere of trepidation that opened the fair, with Beirut suffering recent attacks, the security situation looking shaky at best, and an eerie blanket of snow covering the city.

Editor-in-Chief of Beirut-based publisher Dar Al-Saqi, Ranya Al-Moallem, believes that the situation at the event is actually not markedly different to that last of year. “It is true that there are certainly less visitors this year, but there is no point in receiving a large number of visitors without converting them into sales,” she says. “This year, while there are less visitors overall, we have noticed that a larger proportion of them are buying.” Moallem also notes that Dar Al-Saqi has released the same number of new titles as the previous year, 40, and that international sales have not suffered greatly. “The [Arab-language] book remains in good health,” she says.

Rana Idris is the owner of another Beirut-based publisher, Dar Al-Aadaab, and she is also presenting an optimistic front. She says that, like Dar Al-Saqi, her publisher has also released 40 new titles this year, and demand is still strong for heavyweight authors like Edward Said, Elias Khouri, Hanan Al-Sheikh, Huda Barakat, Samah Idris, Shawqi Bazee’a and Mohammad Shams El-Din, as well as a spike in interest in Turkish novels.

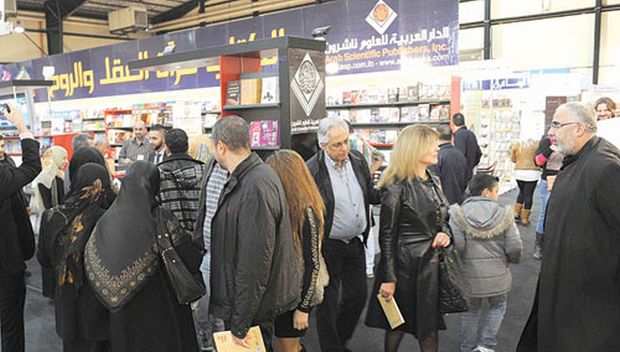

Idris showered praise on visitors to the fair. “I salute Lebanese readers,” she says. “They have never let this fair down, no matter how bad circumstances are. Even this year, with the deplorable economic situation, the bad weather and the snow, as well as the blasts and the security situation, they have still turned out in their droves.”

Novelist and owner of the Dar Al-Jadid publishing house Rasha Al-Amir, though happy with this year’s exhibition—“This has been a very good year,” she says—is also looking ahead to the future. In an ever-changing world where countries, professions and whole industries are becoming ever more interconnected, she says, and where the book publishing industry has shifted from printed to digital format, Amir believes publishers in the region need to be open to new ideas regarding their industry. To that end, she sees the next natural step for the fair would be to integrate it with the Francophone Book Fair, an event which hosts publishers and authors from the French-speaking world and is also held annually in Beirut, usually closing just days before its Arab counterpart opens its doors to visitors.

“I am becoming more and more convinced about this idea of a multilingual book fair,” she says. “The French [organizers] are, too, and they have welcomed this merger and have made their interest clear. It must be obvious to them that the Francophone political project was a failure, while having a dialogue with other cultures and languages will prove more beneficial to them.”

Amir views the world of publishing and books through two different lenses: commerce—and this is of less importance to her—and destiny: “And by ‘destiny,’ I mean the destiny of the region,” she says. Amir sees the Middle East as a varied collection of “minorities” rather than as an invariable monolith. “The whole world is now simply a collection of minorities,” she says. “This year, even the Iranians have a stand at the fair. The next step would be to invite the Turks. Why do the Moroccan or Algerian publishing houses not come to the fair? We must convince them to come and explain the benefits they would reap if they did.”

“Beirut is still a beautiful place to meet and celebrate,” she continues. “We need a fair that adequately represents us [Arabic speakers] and our capabilities, without seeking to superficially please the West nor to betray our language. We do not need a fair composed of shop windows like [the] Frankfurt [Book Fair], we need one that reflects our pluralism both seamlessly and intelligently, and without promoting an Orientalist perspective.”

Amir sees the world of books as a way to help us as individuals and societies navigate the turbulent waters of globalization, helping us to benefit from it where we can. “Books are symbols,” she says. “And book fairs such as this are like laboratories for these symbols. During these frightening and violent times we must not be afraid. We must instead innovate and move forward. We say to the whole world: ‘Welcome to our beautiful fair. We have much to say that is universal and can appeal to speakers of all different languages.”

Amir says she is currently in contact with French and other European organizers of book fairs, as well as Americans and Arabs. The latter group, she says, is fully open to new ideas. “A unified but multinational exhibition will be the quantum leap that will propel books into instruments that will be able to benefit us during this very transitional and turbulent era in which we live,” she continues.

“The exhibition in its current form and under the current circumstances must please publishers, because it never retreats,” says Nabil Marwah, owner of the Dar Al-Intishar Al-Araby publishing house. “But it never moves forward, either.” Marwah believes that the main draw for visitors remains the “social side” of books and the desire to hunt down the autographs of their favorite authors. He stresses the need to promote fair to visitors via social networking websites, which, he says, are now playing a “major role” in marketing new, and especially young, authors.

It is difficult to gauge readers’ moods and tastes almost three years after the Arab Spring. However, it does not seem that the veritable shower of books that have been published in an attempt to keep pace with and chronicle the events has proven particularly popular. After all, the events these authors sought to chronicle remain ongoing and so the reader therefore looks to news sources to become more informed about them. Moallem and Idris see a trend toward escapism through rising sales of novels; Marwah, on the other hand, sees factual books, which his Dar Al-Intishar Al-Araby specializes in, as the more popular current choice, and which he says have excellent sales records at Arab book fairs this year.

What is clear—book fairs and libraries notwithstanding—is that Arab-language books are not the commodities their publishers claim them to be. In general publishers do accept that, as things stand, times are tough for their industry.

Others, and they remain a minority, see the way out of the current predicament as being one of embracing new paradigm shifts in the way they conceive of books and what they can do.