In 1966 Ghitani was imprisoned for criticizing the regime of former president Gamal Abdel Nasser in some of his works. His writings since then have reflected this experience as well as those of living through Egypt’s defining 1967 and 1973 wars with Israel.

Ghitani started his journalism career in 1969 at the Egyptian newspaper Akhbar El-Yom. In 1985 he became the editor-in-chief of the Al-Akhbar newspaper and later the editor-in chief of the leading Egyptian literary weekly, Akhbar Al-Adab—a position he held until 2011.

Of all his literature Ghitani is perhaps best known for his historical novel Zayni Barakat, which in 1990 became Penguin’s first English translation of an Arabic-language novel.

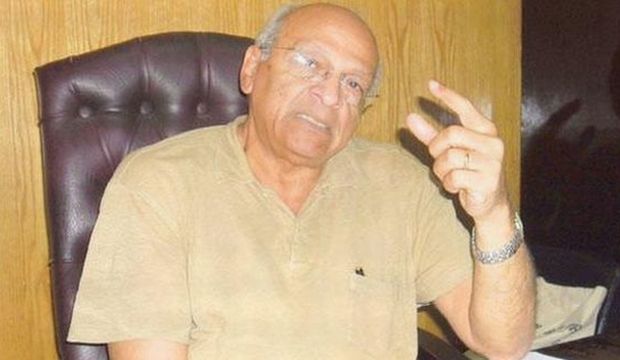

Ghitani has been awarded the Egyptian National Prize for Literature and the French Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres for his work. Here he shares his thoughts on Egypt’s current environment with Asharq Al-Awsat.

Asharq Al-Awsat: Let’s start with the current political scene in Egypt. How do you view it?

Gamal El-Ghitani: I am cautiously optimistic. I’m cautious because I’m aware of the insistence by foreign players to support local elements to topple the state. I am not talking about changing the regime; for the first time in Egypt’s modern—and perhaps ancient—history, we are exposed to a process of overthrowing the state, not the regime. Regimes come and go, and the July [1952] revolution that toppled a regime [The Egyptian Monarchy] but did not destroy state institutions is a case in point.

In order to understand the situation we are in today, we have to go back to the January 25 revolution, which saw people truly taking to the streets before suspicious and hidden elements joined in. Some of them are still operating now.

The Egyptian spirit we witnessed on June 30 [2013; the mass protests against former president Mohamed Mursi] is gradually diminishing; and this is what I fear. But at the same time there are reassuring signs represented by the fact that awareness among the Egyptian public is higher than that among some of the elite who trade in liberal and pan-Arab slogans.

Q: Do you see the current situation in Egypt as a consequence of the Arab Spring?

I do not feel comfortable with that term; it is suspicious and contrived. The term did not come from Egypt. The issue began in Tunisia, but the target was Egypt as it plays the role of the balancing force in the region.

Q: To what extent do you think it is important for writers to be involved in politics, and how can you combine this involvement with the requirements of creative writing, such as spending time on your own?

Writers cannot be separated from the political reality. During the Second World War, Winston Churchill used to invite writers to his meetings to listen to their opinions. Reading literature and consulting writers helps predict the future. Had Gamal Abdel Nasser read Naguib Mahfouz’s novels, he would have been able to expect what had happened in the Six-Day War. Writers have a comprehensive and panoramic vision, while politicians focus on details only. Since my early beginnings I have never been separated from reality and my work mixes fantasy and reality, treating them as two parallel lines.

Q: Many of your works, such as Dafatir Al-Tadwin (Books of Chronicles), tend to focus on immersion in the self . . .

There are events and circumstances that push humans to immerse themselves in their selves. I went through this experience as I grew older out of the desire to defend myself and rebuild life as quickly as possible because I became aware of the meaning of the brevity of life and mortality. The stage at which I wrote Dafatir Al-Tadwin belongs to this state [of mind].

Q: What is your assessment of Egyptian literary output following the January 25 revolution?

The volume of writing at present is unprecedented even compared to the 1960s, [a period] known for its creative momentum. Without doubt, there was a huge creative output in that decade on all levels, despite the oppression that was present. Nevertheless, I think much is being written now, even more than at that time, but it needs those who can critique it. In a sense, the creative movement is limping along on its own.

Q: Do you mean there is an insufficiency in literary criticism?

Yes, there isn’t a credible critical movement [at the moment]; and the creative output depends on taste. There are some contemporary variables represented by the fact that young writers are publishing online and have a young readership who buy their books once they get published.

There is a huge amount of talent and it all depends on the skillfulness of cultural institutions in supporting the emerging creative writers. Unfortunately, I have noticed that such institutions still operate according to the principle of, “Those with me, and those against me.” In fact, culture officials deploy their own tastes and literary preferences, opposing some writers merely because they do not like them. The Ministry of Culture is supposed to turn into a supporter rather than a producer of culture. As a result, young writers have turned their backs on ministries of culture, and this is evidenced by the fact that the output of the best young literary writers has not come out of state institutions but rather out of private publishing houses, such as Merit [Publishing House].

Q: What is your opinion about the common phenomenon of literary writings featuring vulgar and obscene language?

To begin with, I am against the banning or confiscation of creativity and I oppose interference or censorship in writing. Literature purifies itself by itself.

This is an abridged version of an interview originally conducted in Arabic.