President Donald Trump has to decide what to do with an American who was fighting for ISIS, captured by Kurdish forces in Syria and handed over this week to the US military. The best solution is also the simplest: Charge him with material support for terrorism, convict him and lock him up in an appropriate US prison for many, many years.

In any sane, nonpartisan world, this decision would be a no-brainer. The other options are all flawed — practically, or legally, or both.

An ISIS combatant could likely be detained as a prisoner of war, assuming we are at war with ISIS. That’s probably the case, although it’s worth noting that Congress has authorized war against those who planned the Sept. 11 attacks and against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, but not specifically ISIS.

The trouble is that prisoners of war aren’t supposed to be punished for taking up arms. They’re entitled to the protections of the Geneva Conventions and to be freed when the war is over. They cannot be mistreated or interrogated by violent means.

The only prisoners of war who need not be freed at war’s end are war criminals. The captured American is almost certainly an unlawful combatant under US definitions of war crimes, because he presumably hasn’t been wearing a uniform. Beyond that technical violation, we don’t know what acts he might have committed in fighting for ISIS.

In any event, a war criminal needs to be charged with a war crime by a military tribunal. And there isn’t one in place.

True, the tribunals are up and running at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to try the Sept. 11 planners. But they almost certainly wouldn’t work for the American.

If there is one lesson of the Guantanamo military tribunals, it’s that they are stunningly slow.

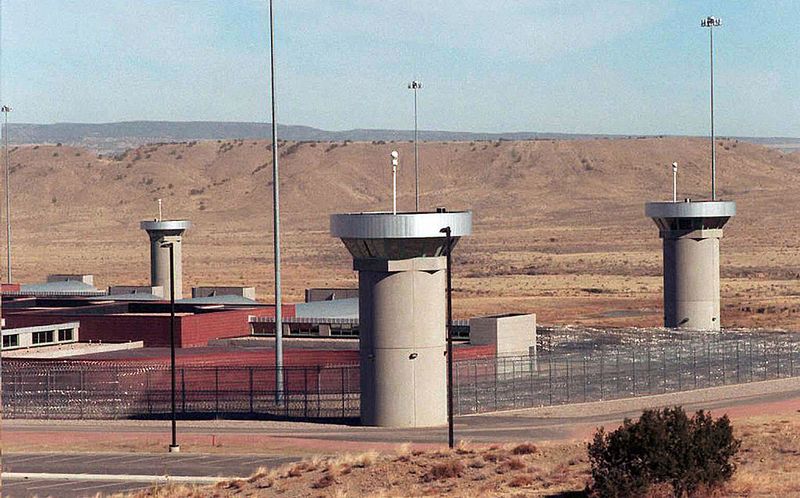

In contrast, a criminal trial could be fast. If the defendant pleads guilty, it could be almost instantaneous. And the American would have good reason to cut a deal in order to reduce his sentence or improve the conditions of his incarceration. After all, he is sure to be found guilty of materially supporting terrorism if he was captured on the battlefield fighting for ISIS. That crime calls for a long sentence, which could easily be served in the miseries of a Supermax prison unit.

That brings us to the issue that has moved some Republicans in the past to criticize the option of criminally charging terrorists: reading them their rights. If charged, the American must be told he has a right to an attorney and a right to remain silent.

Yet that advice likely wouldn’t stop the American from providing intelligence. The incentive to talk comes from the threat of decades in Supermax.

True, he can’t be tortured or mistreated. But that would be unlawful even if he weren’t an American, or weren’t going to prison.

In the past, the government has used a questionable two-step on some detainees. First, it held them incommunicado as prisoners of war aboard US ships for months, subjecting the detainees to questioning by CIA personnel. Then, when they had told what they knew, the government arrested them and read them their rights.

The Trump administration may try this same two-step. But it raises serious constitutional questions about whether anything the detainee might say could ever be used in court.

What’s more, the two-step shows contempt for the independence of the judicial process.

If Trump is worried about being criticized from the right for arresting the ISIS fighter, he can always explain (on Twitter if he chooses) that prison is the only place for an American who takes up arms against innocent people and his country.

The public accepted the criminal prosecution of the so-called American Taliban, John Walker Lindh, who remains in prison. And he was involved in the death of a CIA officer.

All over the world, countries are struggling to find the right way to treat returning ISIS fighters. In the US, the tools and solution are clear. This fighter committed the crime. Now he should do the time.

Bloomberg View