London – Political observers are in almost complete agreement that the social movement that accompanied the recent French presidential elections led to unprecedented changes in the political structure of the country not witnessed since the end of World War II. At the time, Charles de Gaulle assumed power and expanded the privileges of the president, thereby paving the way for what is now known as the Fifth Republic.

It has become clear that the French people have lost patience with traditional politicians and their traditional parties with all of their endless disputes and conspiracies. They have instead turned towards a non-partisan president, who appeared on the French scene about a year ago. He is faced with an opposition that is built on the legacy of the Vichy government and coup leaders of the Algeria war.

Major French politicians were not the only victims of this major upheaval. Along with them fell one of the most important aspects French life, one that has been with it since the French Revolution: the voice of the French cultural and intellectual elite. It became clear amid the domination of the liberals and the extreme right voices that no one in France now listens to what the cultured have to say. The cultural elite have withdrawn with their thoughts and theories into the shadows. They have returned to their universities and specialized centers without leaving a mark on the recent developments.

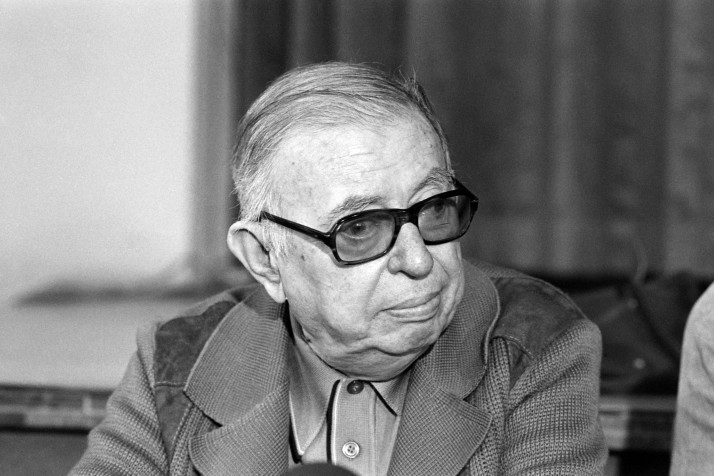

This is not the France of Jean-Paul Sartre and we are no longer in the position of intellectual leadership of the country, commented French philosophy professor. Sartre was the famed leftist philosopher who led the Paris student marches in 1968. Even when he was arrested on charges of civil disobedience, de Gaulle, who was then president, was quick to issue a pardon and release him, telling his men: “France cannot arrest Voltaire.”

De Gaulle’s stance was the best demonstration that France has always distinguished itself from other European countries in that its cultured elite have affected political and social developments. This elite has stood against popular movements and intellectual currents, often ones to the left of the governing body, and defended the poor, the workers and the marginalized, and even the victims of French colonialism.

These cultural figures can trace their roots back to Voltaire, the searing critic of the institutional elite. He was followed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose thoughts on the social contract paved the way for the French Revolution in the 18th century. Victor Hugo expressed the voice of the miserable and marginalized of the 19th century, while Emile Zola, the 20th century novelist and journalist, faced the highest levels of power in the affair of Jewish officer Dreyfus. He wrote his acclaimed article “J’Accuse”, which landed him in jail, but he later went on self-imposed exile in London. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu spent a part of his life leading railway worker strikes and Sartre, the philosopher, was the voice of global leftist issues in the heart of Paris. Albert Camus inspired the generation of the angry 1960s and Michel Foucault altered the nature of general discussions in France, bringing up issues of reforming prisons and the penal code. Jean Baudrillard was the example of the regular Frenchman who exposed the fraud of capitalism. Even at the beginning of the 21st century, French cultural figures preserved their impact on their country. Former President Nicolas Sarkozy consulted the neo-right philosophy of Bernard-Henri Levy when he decided to take part in the ouster of Libya leader Muammar al-Gadhafi in 2011.

Observers attribute this shift in thought to the wave in turning to the right that is dominating western sentiment and which has left its mark among voters, as it did in Britain and its Brexit and in the United States with the election of Donald Trump as president.

This wave was not born out of nothing, but it was a product of the severe depression that plagued the left cultured figured after years of global socialist experiences in the 1980s. The experiences led to their isolation and popular blocs shifted their attention to right, who turned the social conflict from a horizontal divide into a vertical one. There is no doubt that the major disappointment in the rule of the socialists in recent years, before the election of Emmanuel Macron last week, did not help many French people in avoiding falling for the chauvinist popular right spider web.

A quick scan of French bestselling books gives clear evidence of this. At the top of non-literary books lists were the works of Alain Finkielkraut, author of “The Unhappy Identity”, who argued that France is surrendering to Islamists under the excuse of tolerance and liberalism. Éric Zemmour, author of “The French Suicide,” believes that France has lost its identity and called for a return to the golden age of the past.

Even literature bestsellers are focusing on the right. Michel Houellebecq’s book, “Submission,” spoke of the election of a Muslim candidate as president of France in 2022, sparking wide debate in the country. The neoliberal media in France paved the way for such publications to be the focus of talk shows without offering the position of the opposing view. Propaganda, similar to the one in the United States, is now taking center stage in the city of lights. This will likely create further divides between the true French intellectuals and the popular blocs.

There are still intellectuals and philosophers in France, but it seems that they have lost their position as moral guides of this nation, which is inevitably a personal loss for each one of them. The greatest loser however is the entire French nation, including its governing elite, which in the future will find itself at the helm of a republic without a conscience to deter it.