Washington- The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is deceiving employees by sending memos of false information to keep operations secret.

One internal defense official said that the practice is known as “eyewashing”, though it apparently only happens rarely. How it works is that high-level officials place inaccurate information about sensitive operations into regular communications. These same officials then resend the original, unaltered communications only to those cleared to see the information.

In one case, investigators found two memos hinting at the practice. The first was sent to a CIA outpost in Pakistan, and it instructed local operators not to target a specific al-Qaida agent. A second memo, however, told recipients to completely disregard the previous message and to move ahead with the plans.

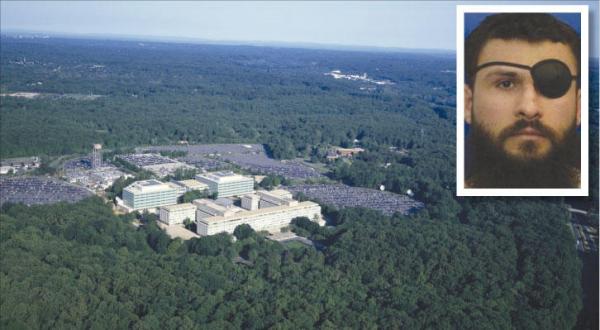

A lengthy section of the Senate report focused on Abu Zubaida, who was considered the first senior al-Qaeda associate that was apprehended after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, described elaborately an apparent case of eyewash.

Before his capture, CIA operatives in Pakistan informed headquarters that they were closing in on Abu Zubaida and apparently asked for guidance on whether they had authority to plan an operation designed to kill him.

CIA officials at headquarters replied with a cable that was disseminated widely among the agency’s agents in Islamabad, warning the station that it had no authority to contemplate such a lethal mission, former U.S. officials said. But that message was superseded by a separate memo telling a small circle of operators that they were clear to proceed.

“When you introduce falsehoods into the communications stream then you can destabilize the whole system of intelligence oversight and compliance with the law,” said Steven Aftergood, a government secrecy expert at the Federation of American Scientists.

“It wasn’t that long ago that we had a CIA executive director who was engaged in criminal activity, you don’t want someone like him preparing eyewash cables,”

Aftergood said, referring to Kyle Foggo, the former executive at the agency who in 2008 pleaded guilty to a corruption charge. “It makes it too easy to conceal misdeeds,” he added.

Fred Hitz, who served as the CIA’s inspector general from 1990 to 1998, said that intentionally deceiving agency employees seemed fraught with risk. “Somebody who is not clued in could take action on the basis of false information,” Hitz said. “That’s really playing with fire.”