TOKYO — Sitting in a drab industrial neighborhood surrounded by warehouses and factories, Astroscale’s Tokyo office seems appropriately located for a company seeking to enter the waste management business.

Only inside do visitors see signs that its founder, Mitsunobu Okada, aspires to be more than an ordinary garbageman. Schoolroom pictures of the planets decorate the door to the meeting room. Satellite mock-ups occupy a corner. Mr. Okada greets guests in a dark blue T-shirt emblazoned with his company’s slogan: Space Sweepers.

Mr. Okada is an entrepreneur with a vision of creating the first trash collection company dedicated to cleaning up some of humanity’s hardest-to-reach rubbish: the spent rocket stages, inert satellites and other debris that have been collecting above Earth since Sputnik ushered in the space age. He launched Astroscale three years ago in the belief that national space agencies were dragging their feet in facing the problem, which could be tackled more quickly by a small private company motivated by profit.

“Let’s face it, waste management isn’t enough for a space agency to convince taxpayers to allocate money,” said Mr. Okada, 43, who put Astroscale’s headquarters in start-up-friendly Singapore but is building its spacecraft in his native Japan, where he found more engineers. “My breakthrough is figuring out how to make this into a business.”

Over the last half-century, low Earth orbit has become so littered with debris that space agencies and scientists warn of the increasing danger of collisions for satellites and manned spacecraft. The United States Air Force now keeps track of about 23,000 pieces of space junk that are big enough — about four inches or larger — to be detected from the ground.

Scientists say there could be tens of millions of smaller particles, such as bolts or chunks of frozen engine coolant, that cannot be discerned from Earth. Even the tiniest pieces move through orbit at speeds fast enough to turn them into potentially deadly projectiles. In 1983, the space shuttle Challenger returned to Earth with a pea-size pit in its windshield from a paint-chip strike.

And plans are being made to make low orbit even busier, and more essential for communications on Earth. Companies like SpaceX and OneWeb are aiming to create vast new networks of hundreds or even thousands of satellites to provide global internet connectivity and cellphone coverage. The growth of traffic increases the risk of collisions that could disrupt communications, as in 2009 when a dormant Russian military satellite slammed into a private American communications satellite, causing brief disruptions for satellite-phone users.

Worse, each strike like that creates a cloud of shrapnel, potentially setting off a chain reaction of collisions that could render low orbit unusable.

“If we don’t start removing these things, the debris environment will become unstable,” said William Ailor, a fellow at the Aerospace Corporation, a federally funded research and development center in California. “We will continue to have a growing debris population that could affect the ability to operate satellites.”

Enter Mr. Okada, a former government official and internet entrepreneur, who said a midlife crisis four years ago prompted him to return to his childhood passion of space. As a teenager in 1988, he flew to Alabama to join the United States Space Camp at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, and later chose to attend business school at Purdue University, the alma mater of his hero, Neil Armstrong.

Later, Mr. Okada realized that he could use his experience in the start-up world — he had founded a software company in 2009 — to get a jump on other space debris projects.

“The projects all smelled like government, not crisp or quick,” he said of conferences he attended to learn about other efforts. “I came from the start-up world where we think in days or weeks, not years.”

He said he has created a two-step plan for making money from debris removal. First, Astroscale plans to launch a 50-pound satellite called IDEA OSG 1 next year aboard a Russian rocket. The craft will carry panels that can measure the number of strikes from debris of even less than a millimeter. Astroscale will use this data to compile the first detailed maps of debris density at various altitudes and locations, which can then be sold to satellite operators and space agencies, Mr. Okada said.

“We need to get revenue at an early stage, even before doing actual debris removal, to prove that we are commercial, as a business,” said Mr. Okada, who added that he had already raised $43 million from investors.

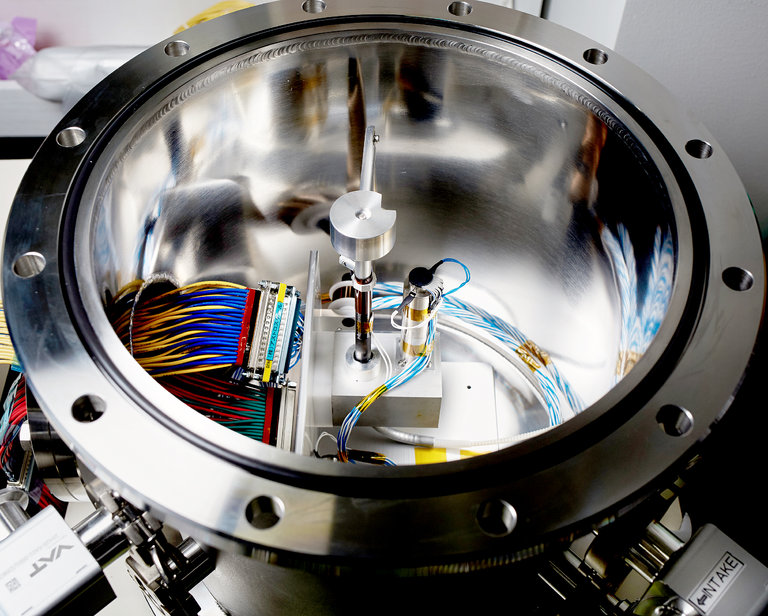

The more ambitious step will come in 2018, when Mr. Okada says Astroscale will launch a craft called the ELSA 1. Larger than its predecessor, the ELSA 1 will be loaded with sensors and maneuvering thrusters that will allow it to track and intercept a piece of debris.

The company settled on a lightweight and simple approach to grabbing space debris: glue. Astroscale has worked with a Japanese chemical company to create an adhesive that would cover a flat surface about the size of a dinner plate on the ELSA 1. The craft would bump into a piece of space junk, which would stick to the craft and be dragged out of orbit. Both the ELSA 1 and the debris would burn up on re-entry.

The concept of deorbiting space junk is not novel. As the debris problem has grown in urgency in recent years, space agencies and companies have released dozens of concepts for cleaning up low Earth orbit.

The Air Force has proposed a “laser broom” that would use ground-based lasers to vaporize a spot on an object’s surface, creating a puff that would act like an engine to push it down toward the atmosphere.

Other proposals call for using robotic arms, nets, tethers and even harpoons to spear debris. The challenge, experts say, is to build an unmanned spacecraft that can be used to track, approach and grab a dark object tumbling through space at 17,000 miles per hour.

“Imagine trying to grab a spinning skater on an ice rink,” said Raymond J. Sedwick, a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Maryland, “except, instead of a person, it’s an S.U.V. And instead of you being there in person, you’re remotely flying a drone, the lighting is bad, you have limited sensory data, there is no obvious place to grab onto, and you might be operating under a time delay.”

“That said, we need to do something” about space debris, Dr. Sedwick said.

Even if a technology works, such efforts face another hurdle: the cost.

Mr. Okada said the key to bringing down a price tag of tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars is to reduce the weight. He said that the Elsa 1’s adhesive would weigh just a few ounces, far less than, say, a 100-pound robotic arm, and that his company’s engineers had found ways to bring the spacecraft’s weight down to 200 pounds, making it much lighter than other proposed craft.

“In the U.S., aerospace engineers are more interested in working on missions to Mars, not waste management,” Mr. Okada said. “Japan doesn’t have so many interesting space missions, so engineers were excited by my idea.”

He also said that Astroscale would start by contracting with companies that will operate big satellite networks to remove their own malfunctioning satellites. He said that if a company has a thousand satellites, several are bound to fail. Astroscale will remove these, allowing the company to fill the gap in its network by replacing the failed unit with a functioning satellite.

“Our first targets won’t be random debris, but our clients’ own satellites,” he said. “We can build up to removing debris as we perfect our technology.”

He said this approach would also get around a hurdle in international law to the removal of space debris — the required permission of the owner. Under a 1967 treaty, man-made objects in space belong to the countries that launched them, and cannot be touched without approval.

Mr. Okada said finding ways around these various barriers was more than a business proposition; it would also be the fulfillment of a childhood dream.

“I see a business opportunity in solving a problem that nobody knows how to solve,” Mr. Okada said. “But my enthusiasm is because I am going back to my teenage passion: space.”

New York Times