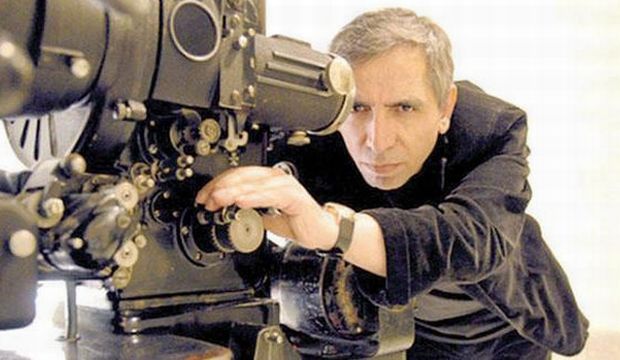

Venice, Asharq Al-Awsat—A decade ago, esteemed Iranian film director Mohsen Makhmalbaf left his home country for Paris, France, taking with him his family: his wife Marziyeh Meshkiny, his two daughters Samira and Hana, and his son Maysam. Today he runs a film production company involving all five family members.

In a career spanning over 30 years, Makhmalbaf has directed more than 20 films. Before the release of his latest movie The President (2014), however, he had been absent from the feature film circuit for some time. Last year, he released a documentary, Ongoing Smile (2013), set in Korea, about a man who embarks on directing his first film at the age of 74. A year earlier, the director had traveled with Maysam to Israel to film another documentary, The Gardener (2012). It was the first time a film had been shot in Israel by an Iranian filmmaker in decades. Makhmalbaf told Asharq Al-Awsat that he chose the location because “the intention was to shoot something about the Bahá’í faith, which originated in Iran but is now prohibited there . . . I chose the closest location to this group.”

As for The President, the plot revolves around the dictator of an unnamed state, known only as “the President,” who suddenly finds himself pursued by the authorities and the citizens formerly under his rule. The character is accompanied on his journey by his young grandson who, unaware of the magnitude of events, knows that his grandfather is an important figure. Throughout his escape the dictator becomes acquainted with various other characters, revealing the extent of the evil of his deeds in the process.

Asharq Al-Awsat spoke to Makhmalbaf shortly after he finished speaking with a crowd of journalists, and he seemed happy to be able to talk to just one person. He was also keen to discuss issues of a non-political nature.

“Since this morning, all the questions about the film have been political, and about why I directed it and what I meant by it, despite the film being far from ambiguous,” he said, adding: “Of course, I’m not blaming the media for raising such questions since the film does have a political viewpoint.”

The following interview contains details of the plot of The President.

Asharq Al-Awsat: How was it working with your family on The President?

Mohsen Makhmalbaf: In the beginning, I thought my family would feel bored and leave me alone, but they didn’t. My wife undertook the script, my son was a co-producer, and Hana was an assistant and a film co-editor.

Q: Currently, your daughter Samira seems absent from the film-directing scene, having directed Blackboards in 2000 and A Two-Legged Horse in 2008. Does she have a new project in the pipeline?

Yes, but my daughter has trouble finding a story that attracts her immediately.

Q: Do you always like to work with your family members?

Yes, they insisted on becoming filmmakers. Each of them wanted to follow in my footsteps and I could not say no to any of them. My son Maysam, my daughter Hana, my daughter Samira and my wife all now work in the filmmaking business. My daughter Samira was 14 years old when she threatened to commit suicide if she could not become a film director. I was aware that all of us would be risking our lives if we continued to work in Iran, so we had to emigrate. My family’s insistence on working with me in this career made me feel extremely comfortable. Yet, because I understood the risks, I did not want any of them to work in the industry. But they insisted on helping me in my work, and we are helping each other.

Q: In The President why did you wish for the name of the state to remain anonymous? The imaginary country you created for the film seems like a real place . . .

This is true. I think the significance is clear: what is introduced by the film has happened, and is happening and will continue to happen. It is a story of dictatorship, revolution, and how dictatorship can steer itself towards destruction. Yet, the revolution may get lost as well. Look at what happened in Libya or at what is happening in Iraq. Is the current situation in Iraq better than the previous one? Saddam Hussein killed citizens but the coup against him resulted in the killing of hundreds of thousands, or even more. Which situation is better?

Q: You give the film an ambiguous ending. Why?

This is true, because it is not the story of one particular president. Had he been killed in the film, the story would have been personal in my opinion, and the ending would have confused the entire issue. I wanted the film to raise questions about what will happen after [the ending]. Will the president die? How will everyone act after the president is arrested? And so on.

Q: When talking about the film recently, you said that the struggle for democracy may also pass through violence. What did you mean by this?

Yes, it is sufficient to look at what is happening around us in the Middle East or in several countries around the world. There is a crucial need to end violence. My film champions the search for such a solution. For me, a film is a route towards change because a film has the strength to change peoples’ mind-sets.

Q: In recent years, Iranian cinema has won many plaudits. What is your opinion about Iranian cinema today? Do you agree that some important films are still being produced in Iran?

In the past few years, Iranian cinema has been placed under additional pressure, especially following the elections [in 2009]. The situation was unbearable, and all my family members were outside Iran because we were in a position to choose between migration and imprisonment. Having traveled to Paris, they [the authorities in Tehran] sent terrorists to kill us. They tried to poison me, and also sent militants to kill me. The French police warned me and sent personal guards to protect me. I could not stand this and I had to change my place of residence.

Q: What about the situation in Iran for filmmakers such as Jafar Panahi, who was banned from filmmaking in Iran for 20 years?

The situation is the same whether inside or outside Iran. Bahman Ghobadi [whose brother Behrouz, another filmmaker, was imprisoned] now lives in Kurdistan, whereas Abbas Kiarostami lives in Iran but is directing his films abroad. Some film directors in Iran are taken to court.

Q: But what about the acclaim Iranian films have won in recent years? Is this because of the value of these films, or the political situation?

I think the films themselves have commanded [acclaim], aside from the international festivals’ interest in aiding Iranian film directors. But I should admit that Iranian cinema is good.

Q: Iranian cinema was also highly regarded prior to Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi’s ouster in 1979 . . .

Of course, Iranian people love cinema. At the beginning, poetry was the voice of Iranian culture; today, cinema has taken over. For my film, Hello Cinema (1994), I announced that I had some roles I wanted to give out to whoever was interested. To my surprise, thousands of people flocked to ask for these few roles. The audience is well aware of the strength of cinema. Banned films [in Iran] are circulated on the black market and millions of copies are sold. Three million copies of one of my banned films have been sold.

Q: I think it is a safe bet that any discussions about The President will very likely focus on its political aspect. Does this bother you? Do you want to discuss the making of this film?

Of course. I welcome any discussions about working techniques and the making and production of the film. Talk of the political aspect alone is tiresome because, as I said, the film is clear [in its message]. Nevertheless, I know that the political message is the thing that attracts close attention. This is undeniable.

Q: What, then, is the precise political message you want to convey in this film?

First, I think that when we are born, we are all equal, including dictators. But the question as to how some of us become dictators is something that can be decided by numerous circumstances. The message of the film is not only about a dictator president or about how he escaped for fear of his life or his grandson’s. In the film, I tried to define the individual as a human and to criticize the passive aspect of his character. This goes for both sides: the dictator’s and the opposition’s.

My main massage in this film is criticizing violence, rather than criticizing the dictatorship. I showed the negative aspects of the dictator as well as that of the opposition, which could also lead to a similar dictatorship. We need to spread the culture of peace everywhere. It is something that should begin at the grassroots.