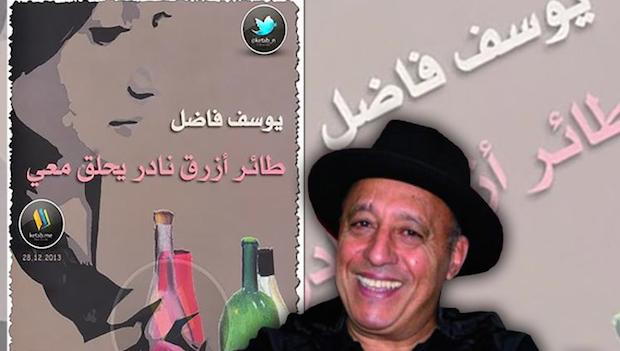

London, Asharq Al-Awsat—In his latest book, A Rare Blue Bird that Flies with Me, Moroccan writer Youssef Fadel takes the reader on a vividly imaginative odyssey through a dreary period of Morocco’s history. Fadel’s ninth novel is a fictional testament to the Years of Lead in the 1970s and 1980s, which saw unprecedented levels of government violence against the opposition in Morocco.

Fadel’s handling of this period, on which much ink has already been spilled, is novel in the sense that he employs elements of fantasy and the supernatural. While it is true that it sheds light on government violations in Morocco’s secret prisons, A Rare Blue Bird is awash with what Fadel calls “patriarchal violence”: the “ordinary injustice” practiced outside prison, on the streets, at schools and in families. For Fadel, systematic violence in prison is nothing but an “echo” of that which is perpetrated outside.

Considered by critics as a sequel to A Beautiful White Cat that Walks with Me—a claim Fadel disputes in this interview—Fadel’s most recent novel traces a complex narrative network consisting of six voices. Each of which recounts a different side of the story of Aziz, a pilot whose passion for the open, blue sky lands him in an abysmal jail. Ignorant of Aziz’s whereabouts, his wife, Zina, embarks on an 18-year quest to find the husband she was separated from on her wedding day.

Asharq Al-Awsat: A Rare Blue Bird that Flies with Me is a delicate title whose poetic aestheticism stands in stark contrast with the cruelty and brutality we see in the novel. What is the relationship between the title and the content of the novel?

Youssef Fadel: The relationship between the title and the novel is similar to that between the protagonist, his past and his future: the pilot, the plane and the bird. [The protagonist] plunges to the bottom, to the nadir of the inferno—the bottom that opens into space. One has no choice but to spread your their and fly; whether in reality or fiction, it makes no difference.

Q: You had a personal experience in prison. Could you tell us about this experience and how it impacted your work as a novelist?

Imprisonment is always a tough experience, particularly at the beginning. Torture and interrogation could take place at any time, day or night. While your body refuses food, your inmate, who happens to come before you, devours your meal ravenously. You do not know where you are or how long you are going to stay, until one day you do not remember when you entered prison. You share with your jailor a mouthful of bread and some passing jokes.

Later, within the extreme confines of the most barbaric manifestations of this human experience, you find out that you can get used to it, and this is the most terrible aspect of the experience. Later on, following your release—having passed all this time—the experience would undoubtedly have an impact somehow. I have never wondered—nor do I find it necessary to—about the way in which my experience in prison has infiltrated my literary career.

Q: A Rare Blue Bird is the second novel in the trilogy that deals with the Years of Lead, after A Beautiful White Cat that Walks with Me. Can you tell us about the difference between the two works, and also your forthcoming novel that deals with the same period?

When I was writing A Beautiful White Cat that Walks with Me, I was not thinking about it as a part of a trilogy. I even find the term “trilogy” an exaggeration. What is common between these two works and the forthcoming one is that they all cover the same period, the 1980s. We might call it a trilogy figuratively, without necessarily having incidents or characters in common, as is the case with the previous works.

Q: What distinguishes your recent novel from the mainstream Arab prison literature is the element of fantasy. Instead of only portraying Aziz’s suffering in prison, you show him growing and spreading his wings before flying off, in an epic scene reminiscent of the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Can you tell us about your use of fantasy in A Rare Blue Bird?

Personally speaking, I believe that the entire experience [of the protagonist] is a fantasy: For the protagonist to start in the sky and end up in hell, to kiss his wife after 26 years of marriage, to spend his days searching for a treasure in a cell that is 6 meters square, and for a woman to spend her life searching for her man. That the remaining elements identify with each other and melt into a one nightmarish atmosphere is no less normal. The situation we were in was a pure fantasy, leaving one with no choice but to flee for their life.

And [stylistic] matters are not a choice that the writer makes. They are forms that impose themselves and take shape in the characters’ behavior before [the writer’s] consciousness. For me, there is no other way of writing this novel. If one is to argue in different terms, one question arises: How is one to make of such events—which have been much discussed, heavily reported by newspapers, and elaborated on in the diaries of those who left prison alive and in their televised testimonies—a completely new novel?

Q: A Rare Blue Bird highlights dictatorship and violence outside prison by presenting a number of tyrannical figures, such as the pimp, Juju, the domineering father and the cruel uncle. Do you have anything to say to that?

What we see inside prison is nothing but an echo of what happens outside. We live in a society where patriarchal violence is committed excessively in the street, at school and in the family. Whether in [one’s] behavior or education, consciously or unconsciously, there are minor and major dictatorships with unknown victims falling and distorted histories being written. The writer attempts to throw light on the hidden aspects of ordinary injustice.

Q: The use of spoken Moroccan dialect in the novel is remarkable. Don’t you think this risks distancing the book from your readers in the Mashreq?

In these two novels in particular I only rarely used the spoken Moroccan dialect, preferring to limit the dialogue to a basic form and use the indirect style, which imparts a touch of dynamism to the novel. In addition, the spoken dialect is not so detached from classical Arabic—only in a few cases.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks