WASHINGTON — President Trump’s failure to push through the broad health care overhaul he promised has raised questions about the prospects of a sweeping rewrite of the tax code. It is a politically fraught and dizzyingly complex endeavor that pits powerful interests against one another and threatens to increase the federal deficit.

“Trump has to win on this,” said Stephen Moore, a distinguished visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation who advised Mr. Trump on tax policy during his campaign and transition. “There’s no margin for error here, and failure is just not an option.”

Just how difficult will it be? Here are five obstacles to getting a new tax law:

A leadership vacuum

The greatest hurdle to a tax overhaul may be the White House itself. Mr. Trump has yet to make basic decisions about the structure and scope of his plan, the strategy for pushing it through Congress or even who in his administration will be in charge of crafting and selling it. While White House officials said they would unveil a plan weeks ago, one has not materialized.

“Obviously, we’re driving the train on this,” Sean Spicer, the White House press secretary, told reporters on Monday as he deflected basic questions about what the president’s proposal would look like. That is hardly obvious to many members of Congress, administration insiders and outside observers who now question whether Mr. Trump and his close advisers are capable of executing on such an ambitious and high-stakes negotiation.

Steven T. Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, will most likely play a major role in devising a tax package. He said last week that the administration would soon release a plan. He also predicted that the tax effort would be easier than health care, a notion that many longtime congressional aides consider laughable. With many central jobs still unfilled at the Treasury Department, Mr. Mnuchin does not yet have the number-crunching and policy-analyzing firepower he needs to lead a major tax overhaul effort.

Then there is Gary Cohn, the director of Mr. Trump’s National Economic Council, who has told people that he is leading the president’s tax overhaul effort. Mr. Cohn, a former Goldman Sachs executive, has expressed interest in using revenue raised by a special tax on American companies’ offshore earnings to finance a major infrastructure rebuilding effort, an approach that could have some appeal among Democrats eager to see new spending on roads and bridges.

Deficits and debt

Many Republicans in Congress — up until recently including Mr. Trump’s own budget director, Mick Mulvaney — are deficit hawks. Their deeply held conviction is that any tax overhaul should not add to the national debt. The president, who as a businessman proudly called himself the “king of debt,” has accepted no such constraints. During his presidential campaign, he proposed a tax cut plan that would add an estimated $7.2 trillion to the $20 trillion national debt over a decade.

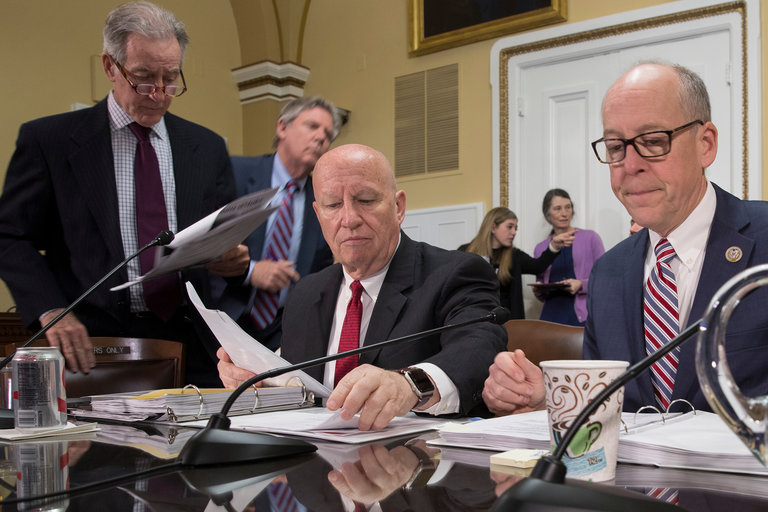

Yet House Speaker Paul D. Ryan and Representative Kevin Brady, Republican of Texas and the chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee, are among those who have held firm to the idea of a tax overhaul that does not increase the debt.

“I’m optimistic that Republicans still very much care about balancing the federal budget,” Mr. Brady said. “And in truth, this doesn’t have to be a choice.”

But choices will have to be made.

The border tax showdown

One choice dividing Republicans is whether to include a large import tax, also known as a “border adjustment tax” in the package. Mr. Ryan and Mr. Brady have been aggressively pushing the inclusion of a 20 percent tax on imports that they think would raise as much as $1 trillion to offset cuts in individual and business tax rates.

Such a proposal appeals to Mr. Trump’s instinct for toughness at the border, promoting American-made products and igniting the creation of new manufacturing jobs. While he has sent mixed signals about whether he supports including it in a tax overhaul, the president told The New York Times this month that he did. “I’m the king of that,” he said.

But the proposal has already created a sharp split within the business community. Retail giants like Walmart are bitterly opposed and willing to wage a costly advertising war against a plan they argue will increase the price of their products and end up raising prices for American consumers. Industrial companies that are heavily dependent on exports support the idea.

The winners-and-losers effect

It is a cliché in Washington to say that tax reform creates winners and losers. But it is true, and that is one of the most formidable obstacles that has frustrated previous efforts at enacting broad changes to the tax code.

The tax code is riddled with special-interest provisions and deductions enacted over many decades. Reorienting is bound to give advantages to certain groups and impose disadvantages on others.

Popular tax breaks for individuals such as deductions for mortgage interest, charitable giving, and state and local taxes account for huge amounts of revenue. They would probably have to be curbed or eliminated in order to compensate for bringing down tax rates. Both Mr. Trump and Mr. Brady have proposed doing so.

The real estate industry, charitable groups, municipal bond traders, and state and local governments are just a few of the constituencies that are likely to revolt at the first hint of such changes. And they could be expected to spend freely to defeat them.

Rules, rules, rules

The arcane procedural rules of Congress — the same ones that contributed to the demise of the health care repeal bill — will complicate the process of pushing through a tax overhaul. The White House and congressional Republicans would need to decide whether to use a process known as budget reconciliation to speed changes through Congress on a simple majority vote or allow the legislation to proceed under normal rules. Go with the normal rules and they would need 60 votes in the Senate — including some Democratic support — to pass it.

Because of the strictures of the reconciliation process, the plan would not be allowed to add to deficits outside of a 10-year budget window. That is why President George W. Bush had to include a sunset provision in his tax cuts of 2001 and 2003.

But businesses that crave long-term certainty are not likely to favor such an impermanent approach. And on Monday, Mr. Brady said he had no intention of producing such a plan.

“If we’re serious about leapfrogging America back to the lead of the pack, if we’re serious about creating jobs and jump-starting this economy, a 10-year bill will not accomplish either of those,” Mr. Brady said. “The most pro-growth tax reform is a permanent tax reform.”

That is a lot that could go wrong. Notice we have not even mentioned Democratic opposition.

(The New York Times)