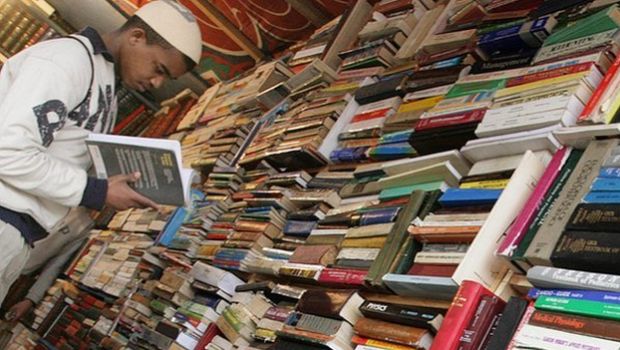

A man browses books at the 38th Cairo International Book Fair in Cairo, Egypt, in January 2007. (AFP Photo)

Cairo, Asharq Al-Awsat—Why do so many literary pioneers in the Middle East, starting out as poets, novelists and critics cross over into publishing? Is it a question of money? Or, is there a need to redefine the relationship between creative innovators and publishers? Many writers believe state-run publishers stifle their creativity, since much of their work is rejected by the latter under the pretext that it is blasphemous, libelous, or offensive to the society’s customs and traditions.

However writers making the jump into publishing is nothing new, and this phenomenon is especially prevalent in Egypt. Asharq Al-Awsat spoke to a number of poets and writers who have also opened publishing houses in the country.

Taher Al-Barbari, a novelist and translator who also owns the Arabesque publishing house, said that the industry needs writers to counteract the control exerted over cultural products by state-owned publishers. He said that in certain regional countries, governments “barricade themselves behind a set of bureaucratic cultural institutions in a bid to make cultural production comply with the status quo,” particularly citing literature. Private publishing houses are therefore one of the best ways for writers to avoid censorship, whether cultural or judicial.

He said: “A writer, artist or critic becoming a publisher is not easy. They should be prepared to see the ugly face of the world; and deal with the headaches of bureaucracy such as organizing paper suppliers, paying taxes, and passing security checks, all while travelling to a publishing house located in the narrow lanes of a town far from the capital city.”

“the last obstacle a publisher faces is the booksellers who tend to see publishers as surplus to the book market, although they are in fact the first port of call in the process,” he added.

Barbari concludes that being a publisher can be an agonizing experience. “You do not need to spend a long time in this industry to discover it is an absurd world that has no beginning or end,” he says, lamenting the quick turnover in the emergence of new publishers and publishing houses.

Arabesque has published several important titles in poetry and fiction, including original works and translation. Barbari, who now works in the Gulf, says he is seeking to establish a financial base to assist him in setting up a truly independent publishing house, free of bureaucratic constraints.

“My ambition is a modest and extremely realistic one: I want the publishing house to have its own press [printing facilities] so that we can run the publishing process actively and freely in a manner that reflects on the creative writer and the publisher as well, hence making the relationship between both sides a truly innovative one on all levels,” he told Asharq Al-Awsat.

This same ambition is held by Faris Khedr, a poet and owner of Al-Adham publishing house. In less than three years his company has already attracted the attention of a number of prominent Arab writers and poets, securing a prestigious position in the Arab publishing world.

Khedr told Asharq Al-Awsat: “Going through the publishing experience is like escaping to an old dream. I could not stand the dramatic alterations after the [Egyptian] revolution, and I chose to settle in my corner. I dreamed of being a book manufacturer, knowing the different kinds and smells of paper, and knowing their quality by touch.”

There were times when the experience was more of a nightmare than a dream, Khedr says. Although Al-Adham publishing house has published over two hundred titles, Khedr has seen no financial return for all his hard work over the past two and a half years. But he still has hope: “I think I’m getting closer to fulfilling my dream thanks to the love and the encouragement I have received,” he said.

Speaking of the publishing process within Al-Adham publishing house, Khedr said: “Small publishing houses open up a wider horizon for the work of new young writers because their margin of freedom is wider than that of large publishing houses associated with government institutions.”

He explains that many independent publishers are understandably aggrieved that they do not receive proper royalties from most bookshops, which he says sometimes behave like “thugs”.

Nevertheless, small publishers have made a genuine contribution to Egypt’s book market, Khedr maintains. The high quality of the works they produce has forced established publishers, who tend to deal with big names, to reach out to budding writers.

With a sad tone, Khedr, who is also the editor in chief of Al-Shi’r [Poetry] magazine, adds that “the most that a small publishing house can do for a creative writer is to organize book-signing events.” He says that, unfortunately, independent publishers are incapable of making and marketing celebrity writers. “All that remains for a small publishing house is to present books that are fundamentally different from the ones being thrown at readers day and night by state-owned publishers.”

Expressing regret at the current state of affairs in fledgling publishers, Khedr called on“government institutions to offer help to small publishing houses in the same manner they voluntarily assist major ones as part of an exchange of interests, particularly as the smaller publishing houses are struggling to survive.”

Most literary figures who head up these small publishing houses believe their work should contribute to developing cultural and intellectual awareness. They see their bigger competitors as money-hungry corporations that pay little to no attention to the literary merit of the books that they churn out.

Yasser Shaban, a novelist, translator and owner of Al-Nawafiz publishing house strongly criticizes the types of books that major publishing houses tend to opt for. He says that Egypt’s Ministry of Culture submitted to hard-line religious views, contributing to the deterioration of the publishing process in government-run institutes in a veiled reference to Egypt’s former Muslim Brotherhood-led authorities.

However he said that this issue was even present before the Muslim Brotherhood took power in the country. In the chaos that engulfed Egypt following the January 25 revolution, three novels were retroactively rejected after they had already been published by the Publishing Department of the General Authority for Cultural Palaces, a move that reflected total submission to the demands of the political system at the time. One of Shaban’s novels was among those censored.

He told Asharq Al-Awsat: “Government institutes do not have a practical plan with specific requirements and objectives to produce quality, not quantity, with the aim of promoting culture and also giving a hand to young talents, away from nepotism.”

Poet Al-Jumaili Ahmed, owner of Wa’ad publishing house, holds the same view, confirming that he did not open his own publishing house merely to escape the restrictions that are being imposed on the public presses, but in order to raise the standard of literature being published in the country.

While novelist Ibrahim Abdulmajid, owner of Bait Al-Yasmin publishing house, informed Asharq Al-Awsat that he established his own publishing house specifically to help emerging young talents get published.

“Those talents require someone to sponsor them and publish the good quality work they produce.” he said.

Egypt’s publishing industry has run the political gamut over the past couple of years following the difficult political circumstances that the country has endured. Despite this, independent publishing houses have continued to emerge to challenge the stranglehold of the state-backed giant publishing houses, introducing Egyptian and Arab readers to a library of exciting new writers. The competition at the heart of Egyptian publishing is a well-entrenched one, but so long as there are writers and poets willing to make that leap into publishing, and committed to providing room for each generation of new young writers to express themselves, Arab literature is in safe hands.