An authoritarian regime that had ruled for thirty years finally collapsed. Demonstrators had taken to the streets and toppled the oppressive government, but the country still had to go through a transformation period. The economy was stagnant, Islamists were gaining ever more influence in politics and society, and the military was pushing to regain some of the control they had had under the former regime. In short, it was a painful transition process.

Sound like Egypt? It is not. It is not, in fact, any of the post-Arab Spring countries in the Middle East—that is a description of Indonesia in the late 1990s, after the demise of the Suharto regime. After Suharto’s downfall, Indonesia still had to go through a difficult transition period, which lasted seven years. At the start of the reform period, its economy contracted by 13% because of the political turmoil and the Asian currency crisis. Indonesia experienced very little economic growth for much of its post-revolutionary period, even though stability was established quite quickly.

“Egypt may join the growing world’s economic powerhouse, the BRICS, to form ‘E-BRICS,’ once its economy is back on track,” President Morsi told the Indian paper the Hindu during his official visit to India this March, speaking of the consortium of emerging economies formed by Brazil, Russia, China, India and South Africa. He painted a rosy picture. Yes, there is no doubt that Egypt is a country of great potential, with a sizable population of 85 million, a strategically important geographical location between Africa, Europe and Asia, and an abundant young labor force. However, the short-term economic prospects for Egypt are not as rosy as President Mursi makes them sound.

Once the euphoria waned after the fall of the Mubarak regime on February 11, 2011, Egypt found itself in the middle of complicated situation. Most concerning was the growing social discontent due to widening rifts among political groups and the stagnant economy. This kind of situation is not rare; it is actually very common in countries that have gone through a similar revolutionary period, including Indonesia after 1998, the Philippines in 1986, and many former Soviet or Eastern European countries in the early 1990s. During such a period of turmoil and transformation, it is the people who suffer the most—particularly those who live in poverty.

Shortening this painful transformational period is the responsibility of all leaders and policy makers who take up the task of governing after the fall of authoritarian regimes. Depending on the decisions and actions of those leaders and policy makers, a country can be considered either in its post-revolution period or in an ongoing revolutionary phase. There are two key places that leaders and government officials can look for lessons on shortening this painful transformation period. The first is to learn from the outside by examining other countries’ experiences and lessons. The second is to learn from the inside by looking at its own history, transformational process and mistakes.

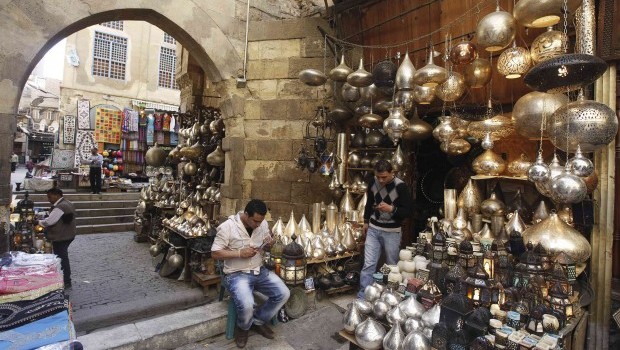

The world is already full of lessons about how to deal with post-revolutionary situations. Why not learn from others who have gone through a similarly painful period? There have already been a few attempts to do so. For example, on February 18 and 19 of this year, the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation of Egypt hosted a seminar in Cairo with the collaboration the Japan International Cooperation Agency. High-ranking officials from the Indonesian Ministry of National Development and Planning and the Ministry of Development of Turkey were also invited. This was one of several initiatives by the Egyptian government to encourage learning from other countries’ experiences. The seminar focused on each country’s process to formulate national master plans for economic development.

Indonesia’s experience can itself give Egypt many useful insights on the transformational period, seeing that political turmoil was not the only challenge it had to face. Over the last ten years, Indonesia has also suffered from terrorist attacks, the devastating earthquake and tsunami in 2004, and the bird flu. After going through so many hardships, today it is said that Indonesia is entering the golden age of its economic growth, with steady annual GDP growth of around 6%. Some even claim that its economic situation is more stable than that of India or China, who are major players in BRICS.

In 2007, ten years after the revolution and three years after President Yudhoyono was elected in the first direct democratic election in 2004, Indonesia regained its 6% growth rate. It is a good demonstration that steady economic growth can be achieved only when political stability is secured. It also shows that achieving political stability and (subsequently) economic growth can take time.

Concerning the relationship between politics and the economy, a book entitled After the Spring: Economic Transitions in the Arab World, published by the Brookings Institution in January 2013, highlights a very interesting point based on an analysis of Russia and the Philippines, amongst other countries. The authors argue that there is a risk of reversion on the political front when political change is not accompanied by widespread economic change, as old vested interests regain control over the political process through their dominance of the economy. Economic stagnation can also affect the power politics game by creating coalitions resisting change.

The future of the IMF agreement is one of the hot topics in Egypt right now, but what matters more is the policy and commitment of the new government towards economic reform. The lessons of world history show that economic reform may bring hardship to constituencies in the short term, but avoiding economic reform will cause bigger political and economic risks in the mid- and long term.

Each country has its own national character, which can sometimes make it difficult to learn from other countries. This is rather evident in the attitudes of those who belong to the bureaucracy of old, authoritarian regimes, and Egypt is no exception. Furthermore, lessons from other countries cannot be useful unless they are adapted to local conditions. The good news is that Egypt’s political newcomers, the Muslim Brotherhood, seem to be keen to learn from other countries, judging from the many delegations they have sent abroad.

Equally important are the lessons that a country can learn from its own history and experience. It is easy to learn from the many mistakes made by the recently-toppled regime, but not all lessons are so easy. New governments often find it difficult to learn from their own mistakes, since nearly everyone has a hard time accepting their own shortcomings.

In Egypt, it is obvious that political polarization has widened since last year’s Presidential Decree that made presidential decisions immune to judicial review. There must have been a strong reason at the time for the president to declare such a decree; however, we must ask what the gains have been made socially, politically and economically as a result. It seems that all the goodwill acquired after the formation of the new government, the reassignment of old military leaders, and successful mediation of the Gaza military confrontation vanished after a single decision.

Any post-revolutionary government tends to have less experienced leaders and policy makers, which is not necessarily a drawback as they are free from the past and from many vested interests. They often have the capacity to think and act outside the box. The difficulty lies in the fact that if emerging leaders lack the capacity to analyze their own actions in a critical manner and use effective feedback in the decision-making process, their country will have a difficult time evolving to a new stage of political and economic development.

Inclusiveness is definitely one of the key factors in the success of nation-building. Political and economic grievances were only part of the causes of the Arab Spring. Dissatisfaction with human rights violations was what drove people to the streets in earnest, eventually toppling four authoritarian regimes across the region. While they were fighting corruption, exclusion and marginalization, people also wanted to feel more involved in their countries’ decision-making and development processes. That is not novel or uncommon: other post-revolutionary countries have gone through the same stages. In order to minimize the suffering of the people during the transformational period after the Arab Spring, determining how to learn and how to be more inclusive are key factors for new leaders and policy makers.