Dubai – The call for “unity” and “union” seems constant and efficient among different religious and ideological movements, each based on their views. However, their call has never been an encouraging unity factor, infact, they were factors of division, fragmentation, and weakness for the nation.

Often, division appears between religious extremist parties more than they appear towards their opponents, like with the fighting groups in Syria, which were recently called for unity by a Jordanian Islamist theorist.

In fact, extremism has originally emerged from dispersion and division; extremist entities reject containment and blow up wills of separations and calls of division.

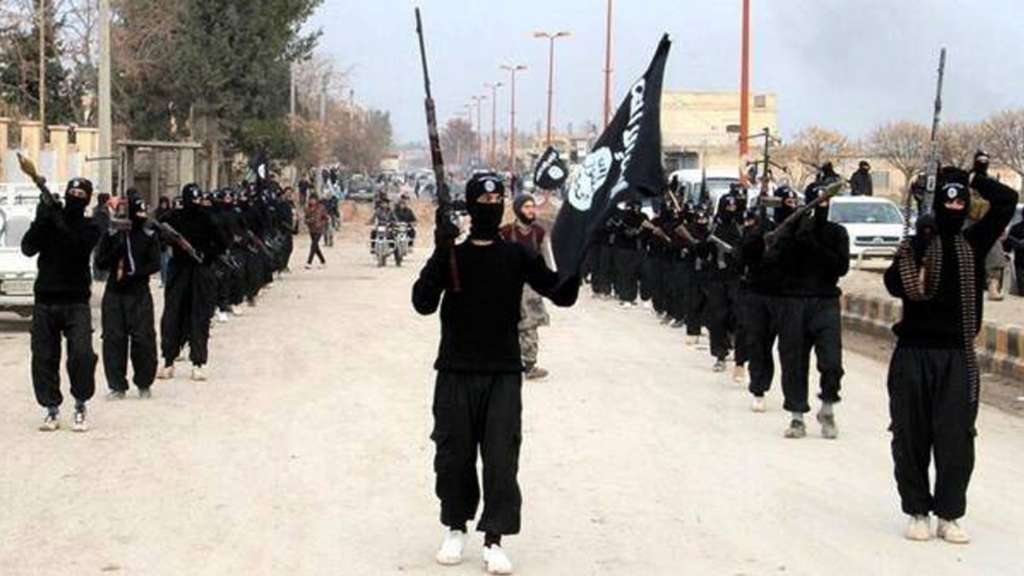

This is how ISIS was born from the heart of al-Qaeda, which also came out from the heart of many previous radical groups.

Moderation has always been the one and only way to achieve unity, because it has the capacity to manage differences and contain them, yet, the right-winged intellects in East and West represent a sort on isolation and simply cannot accept the other. In case these extremist intellects tried to accept others, and if happened it ends with the emergence of divisions in the structure of the one identity and the one entity.

Through history, all extremist groups have failed in achieving unity among different movements, they also failed in unifying the territories they control like what happened among Taliban and the other Afghan militias and among ISIS and the other radical groups. No extremist group, whether an ideological or religious group, has ever succeeded in establishing a strong and unified state; all the Arabian ideological and right-winged experiences in the 50s collapsed swiftly after they lost against the first challenge; only few groups and entities persisted because they depended on different tools like law, history, and politics.

Cases of unity between two extremist groups were rare and those which united were temporary and aimed to fulfill a determined and limited goal, like the union of the “Egyptian Jihad Group” with Mohammad Abdul Salam Faraj in 1979 to assassinate President Anwar Sadat.

Leaders of Afghan Mujahideen also united after the evacuation of the Soviet Union troops in 1989, however, they didn’t wait long before they resumed their fights on authority and influence. In 2004, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi sought to unify radical groups in Iraq in a Shura council, aiming to secure coordination among them, yet he failed after the split of these groups.

On 29 December, the extremist Jordanian Theorist Abu Muhammad al-Maqdesi released a paper calling the fighting groups in Syria to unite and merge. Through this paper, Maqdesi tried to spread his call, which provoked many of Qaeda leaders, who considered that he is seeking to approach ISIS.

Apparently, Maqdesi has used this call to resume his symbolic position among the fighting groups in Syria after the gradual shifts in his speech concerning ISIS. In spite that ISIS launched a vicious verbal war against Maqdesi after it burned the Jordanian Pilot Muath Al-Kasasbeh, the theorist sought to improve his popularity among its members by justifying their acts and denouncing his old statements on the organization and its practices.

Most importantly that Maqdesi’s document emphasized a deep confusion as he called to overcome conflicts among the different groups after he criticized and offended ISIS, the biggest extremist group in this decade.

The unity of extremists has remained a difficult goal, and calls for these unities will also remain weak and limited, especially that they end up with division and fragmentation.