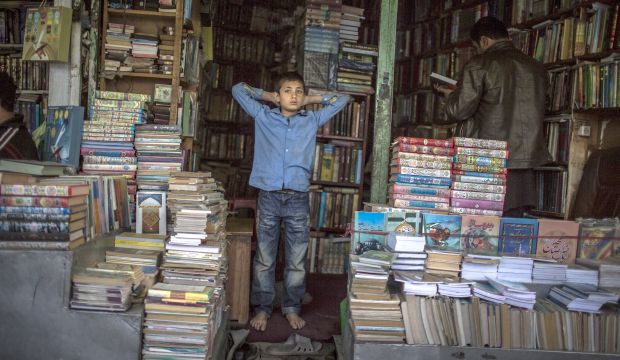

An Afghan boy looks out from a book store in the Old City on November 7, 2012 in Kabul, Afghanistan. (Daniel Berehulak/Getty Images)

London, Asharq Al-Awsat—Afghanistan, which has long been engulfed in civil war and conflict, is producing a wave of migrant literature that is having a positive impact on the literary scene at home.

In next door neighbor Iran, the generation of Afghani refugees born in the Islamic Republic has contributed greatly to the canon of Afghan literature. These writers have been influenced by Iranian poets like Forough Farrokhzad, Fereydoon Moshiri, Sohrab Sepehri, Nader Naderpour and Qeysar Aminpour.

Afghan writers like Hossein Mohammadi, Azizollah Nahofteh and Khaled Nevisa, who lived in Iran and Pakistan for years, have made great strides in promoting Afghan literature at home and abroad.

Azizollah Nahofteh, an Afghan poet and writer living in Sweden, told Asharq Al-Awsat that “without doubt, migration has positively affected Afghan literature. [This has been brought about] by both those who migrated to Iran and Pakistan and those who settled in Western countries.”

Nahofteh, who authored Imaginary Roles, said Afghan publishers have also learnt from publishers in Iran and Pakistan, adding: “Professional editing found its way into Afghanistan following the migration of Afghans to Iran. Today, the best editors are those who have returned from Iran.”

Manouchehr Faradis, a writer and literary critic based in Kabul, said most writers were not driven out by official censorship but self-censorship.

“Except for the 1980s, never have we had an organized group of writers be forced to leave the country by religious censorship in order to be able to write freely,” he said.

Faradis, author of Years of Solitude, said Afghan writers have been affected by self-censorship more than any other form of censorship.

He believes issues such as ethnicity, religion, social status, language, customs and sex are victims of self-censorship in Afghanistan.

Nahofteh believes that Afghans living in the West have been able to shake off self-censorship and focus on sensitive social issues in Afghanistan.

Three decades after the outbreak of war, the emergence of internationally-acclaimed novels such as The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini, The Patience Stone by Atiq Rahimi, Afghani by Aref Farman, and Devil’s Hand by Azizollah Nahofteh touched on some of these controversial issues and provided a window into Afghani culture and society for Western readers.

Nahofteh said Khaled Hosseini’s focus on racial discrimination in The Kite Runner and Atiq Rahimi’s attention to religion and gender issues— taboo subjects in Afghan culture—were new in Afghan writing.

Aref Farman, who also lives in Sweden, said authors-in-exile have an intersectionalist view of everything.

“As far as Afghan authors are concerned, reflection on progress in other countries and backwardness in Afghanistan prompt the Afghan writer to fill voids which show big differences,” said Farman.

“In order not to lag behind in the world, the Afghan writer also makes efforts to win a toehold for himself among famous writers in the world and that is a good thing,” he added.

“For example, Khaled Hosseini, who is among the prominent writers in the world, describes the pain in his home, Afghanistan, as if the world had been neglecting these hurts.”

Farman believes writers like Atiq Rahimi have sought to tell the world that Afghani writers exist. He says Afghanistan is producing serious writers, clearing the way for a better future in Afghanistan.