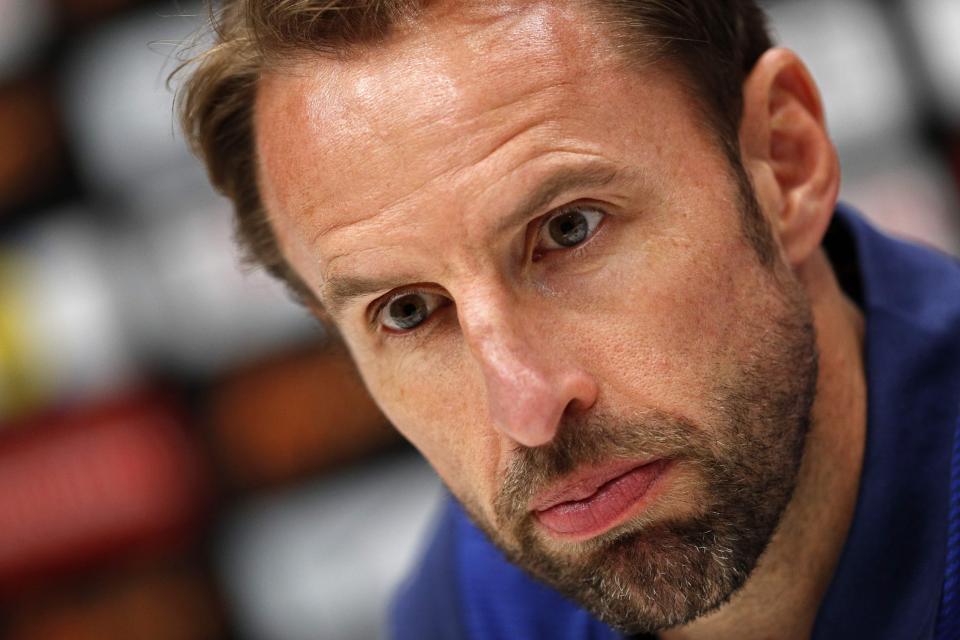

London – The sense of anticlimax was inescapable. Gareth Southgate had spent his evening on the touchline dodging paper airplanes, tedium-induced origami, and blocking out occasional spasms of booing from the home support, and was left to plead for patience after the match. It matters not that plenty of nations would love to be in England’s position. Argentina are in real danger of missing out on a World Cup for the first time since 1970 after drawing with Peru in Buenos Aires. Holland are third in their group and in peril, while even the European champions, Portugal, are facing up to the likelihood of a play-off. The same fate almost certainly awaits Italy. England, in contrast, have emerged unbeaten through another qualification campaign and yet the mood was almost apologetic.

Southgate, asked if he was enjoying himself a year into his tenure, mustered a rueful smile. “Well, weirdly, I am,” he said. “Although I’m not certain I’m standing here thinking: ‘Wow, isn’t it brilliant to have qualified for a World Cup,’ feeling all the love. But I get it, I get it. I go back to the first objective being to qualify, and we have done that. Now we look at how we build, evolve and improve. In international football you don’t have a chequebook of hundreds of millions of pounds to spend. So we have to coach and work to improve people and the team, and that is the great challenge. I get how people are feeling about us at the moment but I also believe in the potential of these players. I want to build a team that the country are proud of.” Now Southgate has Sunday’s qualifier in Lithuania and, at best, four friendly fixtures before he must select a squad for the tournament in Russia. So what areas must England address most urgently if they are to repair the disconnect between team and support?

Conjure some kind of creativity in central midfield

Adam Lallana should have played again for Liverpool by the time England confront Brazil and Germany, Fifa’s top-ranked sides, in friendlies next month and will be reintegrated immediately at international level, but he will find his reputation has soared in absentia. England’s shortcomings are felt most keenly in a lack of creation. Everything was a plod on Thursday, as it has been so often in a qualification campaign littered with slow starts, with the shepherding of the ball as labored as the movement of the players when confronted by massed defense. Oh for a bit of zest, some incision, a burst of quality in the pass. Lallana’s forte is his movement, and his front-foot urgency and aggression in the pass will make a difference. Southgate must wish Jack Wilshere had not slipped so far down the pecking order at Arsenal, for all that he cannot rule out the 25-year-old still making a late case for involvement. “We’re in a position where there’s no way we would dismiss any creative player,” he said. “But, of course, people have to be playing at a good level.”But where are the other options? Has, say, Harry Winks done enough to suggest he can be the answer? Is there anyone else out there? Southgate believes there are players in the system who will go on to impress at the highest level, but they are 18 months to two years away from being ready. So, if the personnel are out of reach, a system of play must be employed that taps better into what qualities the current collective do possess.

Is there scope to explore a back three again?

Arguably England’s most persuasive performance under Southgate’s stewardship was the narrow, and unfortunate, defeat by Germany in March when the manager experimented with a back three with some success. Gary Cahill, Chris Smalling and Michael Keane started in Dortmund behind a pair of midfield anchors, and with the energetic Dele Alli and Lallana supporting Jamie Vardy. There was width and pace from full-back and proper bite on the counterattack. It was a tactic to which the team resorted in the latter stages against Slovenia on Thursday when the visitors went for broke, and it may be an approach that ekes the best from this group against more fancied, enterprising opponents at the finals. England will surely be more of a threat on the break against better teams than they are when asked to break down opponents. Germany and Brazil will test that theory.

Pray English players benefit from involvement in the Champions League latter stages

Southgate was at pains to point to this group’s lack of experience – “they’re young players and most of them have never been to a World Cup so this is a big moment in their careers”– and acknowledged they will find themselves in the company of sides laced with Champions League and league championship winners. That rather overlooked the reality that, in Cahill and Ryan Bertrand, he has two European Cup winners, not to mention players who have claimed the Premier League with Manchester City, Manchester United and Chelsea. But he was right in hoping the likes of Marcus Rashford and Alli, Kyle Walker and John Stones, sharpen their skills in the Champions League this season and thrive at that level. “The younger lads are playing more big games in the Champions League and, if they get to the latter stages and maybe the finals, all these big-pressure games will help this squad,” said Cahill. “We’ve held our own against the likes of Spain and Germany but to have the knack to go on and win those games … that’s something we can learn. To kill teams off when we’re playing well. That’s the gap.” Game management in highly pressurized occasions is something that has to be learned. The more familiar this group’s key players become with tense elite contests, the more likely England are to make an impact in Russia.

So, if we acknowledge we cannot be like Spain, can we be like Iceland?

“Are we going to become Spain in the next eight months?” asked Southgate on Thursday night. “No, we’re not.” But, if we can accept England’s options are not going to blossom unexpectedly, can we not at least aspire to be like Iceland at the World Cup? Not necessarily in style, but in structure, playing to a distinct and clear plan that brings the best out of those available? Iceland’s strength at Euro 2016 was an unswerving belief in their approach and an ability to implement a relatively simple gameplan. The approach only took them so far, of course, and they were found out by France. But, by then, they had seen off England and reached a quarter-final. Southgate would thrill at the prospect of doing likewise in the context of recent tournament traumas. Yet another troubling aspect of England’s qualification is that, for all the talk of progress, on the pitch a clear plan and thought process have not always been evident. The management team feel a plan is being implemented. They believe they are drumming it into the players at every get-together. Yet it is not always easy to notice from the outside looking in. If the supporters can identify what the team are trying to achieve, maybe the skepticism will recede.

The Guardian Sport