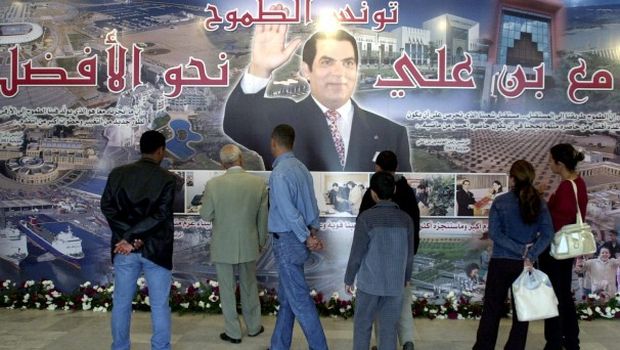

The Tunisian presidency did not hold up for long. Only weeks after publishing the “black book,” a list of journalists and media organizations who were complicit in supporting former president Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali and his regime, the current presidency announced it would launch an investigation into how that list was “leaked” to the press.

This U-turn appears suspicious. For after the presidency announced to the press, with some fanfare, that it would be publishing the list—the first move in a series of “trials” regarding the former regime, it said—here it is saying it will undertake an investigation into how that list was apparently leaked.

The black book scandal drew wide interest from outside Tunisia, with media outlets in both other Arab and Western countries scrutinising the list to see who was on it—and in some cases, how much those included received for their efforts. Especially considering that most of those who were included are still working in Tunisia’s media industry today.

But announcing that an investigation has been launched to reveal who leaked the list is not any less confusing or problematic than publishing the list itself.

It is true that the list reveals the extent of the Ben Ali system of propaganda, as well as the involvement of various media figures from the Arab and Western world in addition to those from Tunisia. But the fact is that the list, which was issued by the current presidency in a bid to symbolically put on trial its predecessor, misses the mark. The presidency announced that the first group that should be held accountable from the Ben Ali era should in fact be the media itself, which it said was complicit in promoting that regime and covering up its crimes.

But the presidency did not wait for the roadmap of transitional justice to be fully worked out so that the revelations can come at a time when there is a proper system of justice in place to hold those accountable. And when it did decide to hold someone accountable, it went for the media—not the judiciary or the security forces or the interior ministry or those who prosecute and jail opposition figures and dissidents. Nor did the presidency seek to investigate the shambolic way the country has been run since the new administration took over, nor the corruption or the businessmen who continue to profit from it.

No. Despite all this, the presidency went for the media. A move designed to distance itself from its own complicity in the current situation by focusing the blame on someone else.

This is not to say that media figures and organizations who paid lip service to the former president and his regime and who chose to ignore its crimes and shortcomings should not be exposed. However, if the current administration wishes to put the former regime and its accomplices on trial—even symbolically—it must consider its priorities. For the institution charged with administering the justice during these trials, and the mechanisms which it uses, must be fully transparent and just.

But that is simply not possible in the current climate. Today journalists and bloggers are still being jailed in Tunisia, and security forces still act arbitrarily. So how then can the presidency confront a malfunction in a sector which is less closely related to it than others—such as the security, judicial or administrative ones?

When President Moncef Marzouki announced he would be launching an investigation into how the black book was leaked, reactions in the Tunisian media were highly critical. And the president is yet to bear the full brunt of his folly. Here, then, is the complicit media which he is seeking to put on trial: lambasting him, where once it was eulogizing Ben Ali.