MISSISSAUGA, Ontario — The troubles began over sermons.

For nearly two decades, Muslim students in the Peel School District, outside Toronto, had been allowed to pray independently on Fridays, part of a policy in many Canadian provinces to accommodate religious beliefs in public schools.

Last fall, the school board decided to standardize the prayer sessions and offer six preapproved sermons that the children could recite, rather than let them use their own.

Muslim students protested, saying the move violated their right to free speech, and the board reversed itself, allowing the children to write their own sermons.

But the dispute unleashed a storm of protest that continued through this spring.

Demonstrators are picketing school board meetings, arguments are erupting on social media about whether religious accommodation is tantamount to special treatment, and there is a petition drive to abolish prayer in the public schools. In April, a local imam who supported the board received a death threat. The local police now guard the school board’s meetings.

The turmoil is one reflection of how Canada’s growing diversity is encountering powerful headwinds, especially in places with significant Muslim populations.

“Although we have a policy of multiculturalism, for most Canadians there is an expectation that immigrants will conform to the mainstream,” said Jeffrey Reitz, the director of the Ethnic, Immigration and Pluralism Studies program at the University of Toronto. “Religious accommodations have been made to various groups, and you’re going to get a backlash once in a while.”

The problems in the Peel schools are a particular kind of conflict in a diverse society, social scientists say — involving immigrants and minorities who challenge aspects of Canada’s cherished multiculturalism.

Since 2013, some Muslim parents in metropolitan Toronto have asked schools to exempt their children from mandatory provincial music classes, citing their belief that Islam forbids listening to or playing musical instruments.

Like its neighbor to the south, Canada is a country of immigrants, helping to fuel a national ethos that celebrates diversity. More than 20 percent of the Canadian population in 2011 was foreign born, a figure that is expected to reach nearly 30 percent by 2031, according to government estimates. In cities like Toronto and Vancouver, the proportion of ethnic minorities could top 60 percent.

The demographic changes have been especially pronounced in metropolitan Toronto, a patchwork of cities and suburban towns bustling with an array of languages and faiths.

School boards like the one in the Peel district are at the forefront of the battles over multiculturalism. The district is among the country’s most diverse, with nearly 60 percent of all residents described as “visible minority,” or nonwhite, according to the 2011 census.

It includes large numbers of Chinese, Filipinos and blacks, but nearly half are categorized as South Asian, a group that includes Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims. The Peel district is home to about 12 percent of Canada’s Muslim population.

In allowing prayer in its schools, the Peel district relied on a provision in the Ontario Human Rights Code that the Ontario Human Rights Commission has interpreted as requiring government-funded schools — both public and Catholic — to “accommodate” students in observing their personal faiths.

Other provinces in Canada have similar policies.

For Farina Siddiqui, 43, a Muslim activist whose children attend public and Catholic schools in the Peel district, allowing students to worship once a week in school is a matter of religious freedom.

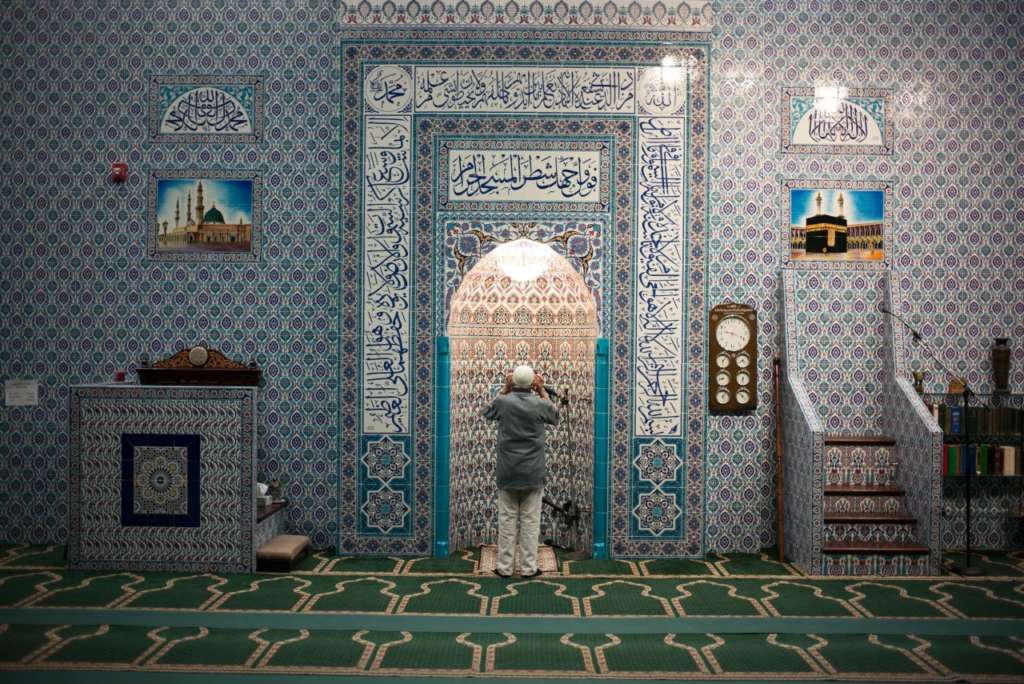

“We’re not asking for schools to provide a prayer hall for everyone to practice a religion,” she said. “We just ask for the right to have a space to pray.” She supported permitting the children to write their own sermons.

Tarun Arora, 40, who works for an outsourcing call center company and immigrated to Canada from India in 2003, said school boards should not be endorsing sermons or allowing prayer in his children’s public schools at all. He wants the schools to be completely secular.

“I’m sending my kids to school for education, but the schools are being treated as religious places, and this is not right,” Mr. Arora said.

He is a member of Keep Religion Out of Our Public Schools, also known as Kroops, a group that formed in January when the board decided to allow the children to write their own sermons. The group has protested outside recent school board meetings and says it plans to bring a lawsuit challenging the policy of allowing prayer in the Peel schools, arguing that the law does not explicitly permit it.

Another group with a similar name, Religion Out of Public Schools, began an online petition to eliminate religious congregation and faith clubs in Canadian schools. It has garnered over 6,500 signatures from people across Canada and the United States.

Many of the petition comments specifically criticize Islam. But in interviews, three members of the group, all of them Indian-Canadian, said they opposed the practice of any religion in public schools, not just Islam.

Renu Mandhane, the chief commissioner of the Human Rights Commission, which is charged with interpreting the Ontario code, said schools had a duty to accommodate religious belief.

(The New York Times)