Claremont, Calif. — What kind of conservative is President Trump? He must be some kind of conservative, because for nearly 100 days and counting, liberals have poured on him the kind of vitriol they do not reserve for moderates or ideological nobodys. Inside the Beltway, some famous conservatives have joined in the sport but for the opposite reason, that Mr. Trump, they claim, is no conservative but a populist demagogue out to discredit and destroy their beloved movement.

In his three major public speeches so far — his remarks at the Republican National Convention, his Inaugural Address and his speech to a joint session of Congress — Mr. Trump did not mention conservatism at all. Even at the Conservative Political Action Conference, he claimed simply, and almost in passing, that his election was a victory for “conservative values.” What those were he did not specify, except to say that Americans believe in “freedom, security and the rule of law” and in standing up for America, American workers and the American flag.

These formulas are sufficiently broad to encourage both sides of the White House jostling between Stephen Bannon, the chief strategist, and Jared Kushner, Mr. Trump’s son-in-law. Rather than focus on the infighting, we need to look at the president’s overall agenda and try to put it into a longer, and sharper, historical perspective.

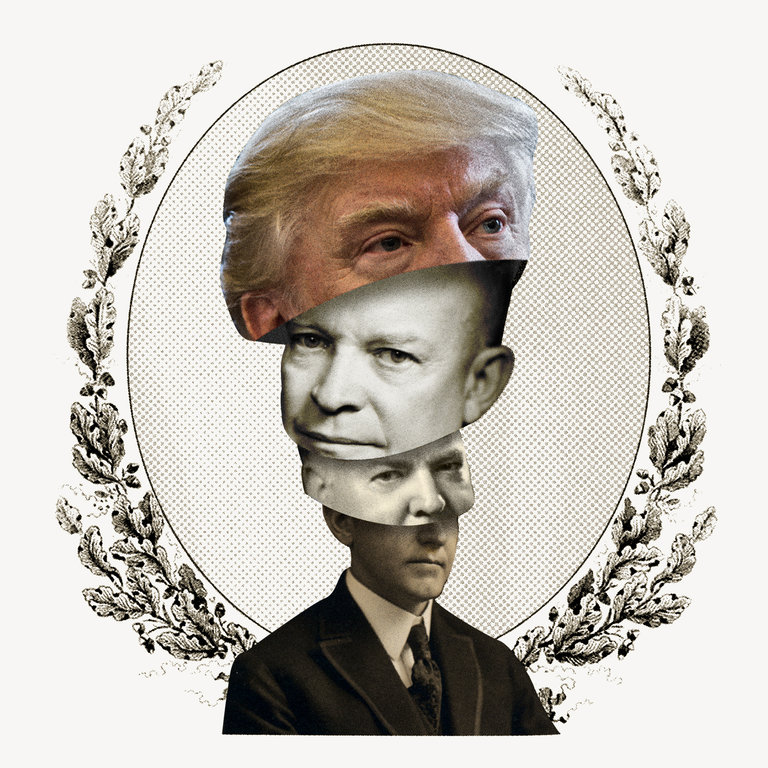

Granted, there has never been a president quite like Mr. Trump, but his positions are not as outré or as outrageous as they are often portrayed.

Mr. Trump remains the kind of conservative president whom one expects to say, proudly and often, “the chief business of the American people is business.”

Although Calvin Coolidge said it first, Mr. Trump shows increasing signs of thinking along broadly Coolidgean lines, and of redirecting Republican policies toward the pre-New Deal, pre-Cold War party of William McKinley and Coolidge, with its roots in the party of Abraham Lincoln.

Mr. Trump is not and never was a movement conservative. Apart from a youthful flirtation (is there any other kind?) with Ayn Rand, he has displayed little to no patience for libertarianism, traditionalism, neoconservatism or the other endangered ideological species that the movement has sought to conserve for so many decades.

“Don’t forget,” he told George Stephanopoulos on ABC News during the campaign, “this is called the Republican Party. It’s not called the Conservative Party.”

He raised in that remark, glancingly, the possibility that conservatism ought to be measured by the standards of Republicanism, or at least ought to be defined in conjunction with Republican principles and history, rather than the other way around — that is, rather than simply taking today’s conservatism as the standard to which to hold the Republican Party. Mr. Trump’s policies suggest that what he calls his “common sense” conservatism harks back to the principles and agenda of the old Republican Party, which reached its peak before the New Deal.

In those days the party stood for protective tariffs, immigration tied to assimilation (or what Theodore Roosevelt called Americanization), judges prepared to strike down state and sometimes federal laws encroaching on constitutional limitations, tax cuts, internal improvements (infrastructure spending, in today’s parlance) and a firm but restrained foreign policy tailored to the defense of the national interest. Are these not the main elements of Trump administration policies?

It’s not that Mr. Trump set out consciously to return the Republican Party to its roots. By temperament and style he’s more attracted to President Andrew Jackson, whose portrait now hangs in the Oval Office. “I’m a fan,” he said after visiting Jackson’s home, the Hermitage, near Nashville, in March. It’s more likely that his own independent reading of our situation led him to similar conclusions and to similar ways of thinking. The bread crumbs he dropped at the joint session pointed in that direction. President Trump quoted a well-known statement by Lincoln in 1847 that “the abandonment of the protective policy” will “produce want and ruin among our people.” Lincoln was a great protectionist before he became the great emancipator.

But Mr. Trump could have as easily quoted McKinley’s 1896 platform (protection is “the bulwark of American industrial independence and the foundation of American development and prosperity”) or Coolidge’s in 1924. Mr. Trump praised Dwight Eisenhower not for ending the Korean War, say, but for building “the last truly great national infrastructure program,” the Interstate System of highways.

The old Republican Party stretched from Lincoln to Herbert Hoover and continued to influence Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. It dominated national politics to an extent that the modern conservative Republican Party, forged during the Cold War, could only dream of: Between Lincoln’s election in 1860 and Hoover’s loss to Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, the party elected every president but two (Grover Cleveland and Woodrow Wilson) and controlled both houses of Congress for about 46 of the 72 years. Those halcyon days coincided with a determined embrace of Trump-like policies. It helped, to be sure, that the Democrats spent those decades living down their shameful support of slavery, secession and Jim Crow.

Yet President Trump cannot simply ignore the modern conservative movement. For one thing, its two great successes, victory in the Cold War and reigniting economic growth (through Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts, spending policies and regulatory reforms), have made plausible his own visions of post-Cold War foreign policy and a resurgent economy. After those successes, however, modern conservatism mostly marked time and dreamed of limiting government. It had vain imaginings of how to build a conservative majority in the electorate, but nothing more.

Mr. Trump offers a way out of the stalemate, toward electoral success and ideological renewal that begins with a return to former Republican policies that put Americans first, on trade, immigration, infrastructure and more, which are attractive to millions of working- and middle-class voters.

The old Republican Party also had a sizable progressive or liberal wing. As his fondness for Jackson shows, Mr. Trump is more a populist than a progressive, but in any case he will be fighting mostly over the party’s definition of conservatism, trying to stretch an orthodoxy, or a clutch of orthodoxies, to accommodate a governing majority. Nonetheless, he will have some room to reach to his left, or to the center, and could invoke Theodore Roosevelt as a model, without necessarily following T.R. on his later Progressive Party bender.

America today is a very different country from what it was in the 1920s or the late 19th century, when Republicans reigned. So the Trump administration’s policies will have to be a mixture of old and new. It’s too early to tell whether this mixture will evolve into a doctrine of Trumpism. Few presidents’ policies, principles and persona are so distinctive that they congeal into an “ism.”

The movement that brought him to power is, by Mr. Trump’s own admission, almost spontaneous and still strangely nameless. It cannot fill the thousands of executive branch positions at his disposal; for that, he needs to rely mainly on the broad conservative movement and the Republican Party.

It’s likely, then, that his administration will have to maneuver between the older and the current strains of conservatism, and between the populist and establishment sensibilities. On foreign policy he has demonstrated a pugnacity easily exceeding the old Republican Party’s. Though he will move trade policy toward greater protection, he will fall far short of McKinley’s standards.

Donald Trump’s populism may be protean, but look for it to move both conservatism and the Republican Party closer to their former selves.

The New York Times