here was an interesting moment at the end of Arsenal’s defeat at Manchester City on Sunday, a match of shifting tides, foggy passages, moments of extreme skill and one decisive tactical switch by Pep Guardiola. Deep into stoppage time, as Petr Cech and the nearest team‑mate dithered over a free-kick by the halfway line Arsène Wenger could be seen leaping up and urging them to get the ball forward, waggling his arms about in that familiar, slightly alarming angry‑pterodactyl style.

Eventually the ball did go forward, just as the final whistle was blown. Wenger stormed back from the touchline, visibly frustrated, turning his back on the yellow shirts closest to him. It felt significant, intentionally or not, that the other player with Cech at the end was Mesut Özil.

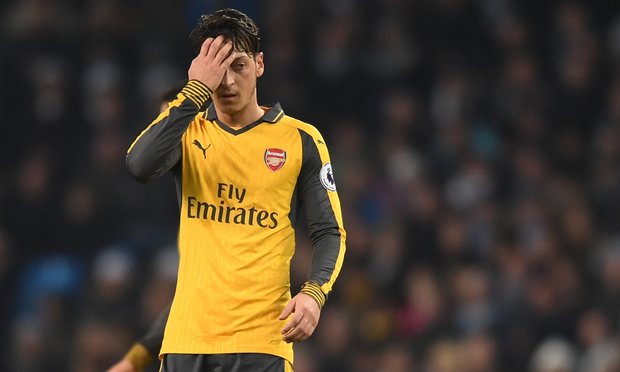

The German remains Wenger’s pet creative genius, a player in whom he has invested huge amounts of patience and reputational points, but Özil was once again an absence at the Etihad Stadium. Aged 28 and now foraging after a bumper new contract, Arsenal’s record signing is surely treading close to the point where even a fond and indulgent manager may start to feel that a beguiling, at times frustrating three years is reaching a point of crisis.

Yes: it’s that Özil conversation. Bring it on. Let’s do this here and now. Although hopefully without the associated mulch of cliché and received ideas, the identity politics of English football that seems to attach itself to any discussion of a genuinely interesting, genuinely alluring footballer.

It is surely obvious by now that nobody seriously expects Özil to “drive” a game on like some elfin Roy Keane or Bryan Robson reimagined as Victorian garden sprite. To criticise Özil for his lack of bite in the tackle, his absence of biceps, the failure to wear a white conical bandage around his head is simply to miss the best of him.

Against this there is a counter‑orthodoxy that suggests criticising Özil is to declare yourself unworthy of his minutely calibrated artisanal brilliance, eyes boggling as he gazes into the shadow world – the ghost passes, the invisible angles – like some frail alien princeling wheeled out to take us beyond our human plane into the footballing nether.

The fact remains he is a lovely footballer, and a committed one too who runs a great deal more than some seem to think (10km more than any other Arsenal midfielder in the Champions League this season). His worth does not lie simply in assists and goals scored. Özil works the fringes, finds passes that make the passes, manages Arsenal’s transitions from defence and generally acts as a high-grade lubricant.

It is, though, still possible to put a measuring stick on all this, just as pretty soon Wenger himself will have to make a significant call on a player who has been a genuine treat even for the Premier League neutral. Özil, or rather the industrial-Özil complex around him, are currently forcing this. There is talk of £290,000-a-week salary demands in any new Arsenal deal, more than double his current contract. It would be a huge pay rise, elevating Özil to genuine A-list status. Two things occur instantly.

First, there is little in Özil’s recent club football that suggests he deserves it. And secondly, it is hard not to conclude such game-changing money would be better spent elsewhere. Arsenal could, for example, try to sign Riyad Mahrez, who is younger and more obviously effective and may just be gettable. Özil is fun, brilliant, maddening at times. But judged by any serious scale of actual impact on this, the earthly realm – where goals and wins and trophies really do exist – there is nothing to justify such extreme demands.

Three seasons and two FA Cup winner’s medals into his Arsenal career Özil isn’t showing any obvious signs of other gears, of a level still to come. He faded with the rest last season as the best chance in a decade to win the league title disappeared, and has been present through the galling Champions League defeats of the last few years.

Özil was supposed to define the endgame of the late Wenger years. And so he has, an emblem of room-temperature stasis, a certain debilitating cosiness. Wenger has been criticised since the defeat at the Etihad for failing to react in real-time, to shift his tactics to mirror Guardiola’s successful rejig into a system with two No10s and David Silva sniping behind. There is no shame in being out-tacticed now and then. But when all this was going on where was Wenger’s senior player, Arsenal’s only World Cup winner on the pitch?

Arsenal fans have become accustomed to shrugging a little at this point and saying, well, it just wasn’t Özil’s game, treating him with the special privileges reserved for some impossibly complex high-spec part in an over-engineered luxury car: the fine-tooth alternator-flange that makes the multi-jet trans-drive work, but which can quite easily be thrown by too much fluff in the rear transponders or, you know, a leaf on the windscreen.

But this isn’t really enough. When your good moments are as good as Özil’s it is easy to overlook the omissions. If we really are going to start talking Messi-level wages there are still quite a few things Özil doesn’t do. Such as kicking the ball with his right foot, always a baffling omission in a top footballer. His finishing can be ropey. In his entire Arsenal career Özil has one goal from outside the box. Being able to shoot seems the least you’d expect for £15m a year. Last season Özil won three headers in the Premier League. So far this time he’s made 11 tackles. Nobody hires Mesut Özil to do either of these things. But there is a kind of entry-level expectation.

Even more so as the game has changed recently. Kevin De Bruyne is an obvious point of comparison, another high-grade northern European No10, but a player who is relentlessly involved even on his off-days. Against Arsenal De Bruyne looked a little muddled in the first half. He kept on running and harrying. He ended up producing the pass of the game to help Raheem Sterling score the winner. The previous weekend against Manchester City Mahrez had even fewer touches than Özil but still decided the match. In the high-speed, high-turnover press of the current Premier League it’s not enough to have off and on games. The day is always there to be seized.

Similarly Arsenal’s switch to playing more without the ball hasn’t brought the best from Özil. Suddenly you notice how little he contributes out of possession, an ambling ghost while those around him press and fill. The days of possession football, where it is enough simply to link and prompt and feed endless high-grade passes the way of some elite centre-forward, are largely gone.

There have of course been some real highs, and hopefully there will be more. Özil was excellent in the 3-0 defeat of Chelsea in the autumn, a result that seems now to have catapulted one of those teams towards a league title. Although not perhaps the one you might have expected. He was there for both of the wins against the current champions last season. But on too many other occasions, and once again on Sunday, Arsenal have struggled against better opponents, not helped by the additional burden of ferrying Özil about the pitch in his imperial litter, waiting for him to do stuff.

Already any serious Arsenal title challenge looks to have faded. In each of the past three seasons opponents energised by some spurting, sparking piece of managerial chemistry have sprinted away around this time of year while Arsenal have still been making plans. Wenger was genuinely upset at the end of Sunday’s defeat, an encouraging sign in itself. At the very least Arsenal’s season might benefit from a little more in the way of tension between a sympathetic manager and a star player who, in every sense, too often seems to leave no shadow.

The Guardian Sport