English football has always had a thing about leadership. What is it exactly? How loud should it be? How many layers of bandage should be entwined around its blood-caked temples? More to the point, without it who will keep the men in check, prevent them from fleeing the trenches, retain some sense of fragile, orderly decline?

More often than not leadership is defined as an absence, a feeling that something brusque and manly and vital has been allowed to wither. Arsenal lack leadership. England lack leadership. In both cases the leadership lacked is of one kind: forceful, muscular, collar-grabbing. Last week Teddy Sheringham suggested Leicester’s players could solve their problems with conditioning, tactics, motivation and personnel not by working on the training field but by getting drunk and “having a bit of a fight”, thereby settling their differences like men, or at least like primates.

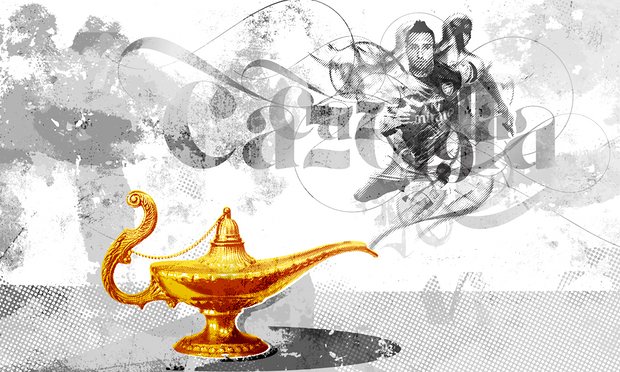

On the other hand, maybe there’s another side to this. In a knockabout week for English football the news that Santi Cazorla will miss the rest of the season through injury was a note of sadness, and not just for those who follow Arsenal. Cazorla has been out since October. On Wednesday he reaggravated his tender ankle ligaments, a third major injury in the last two years.

Cazorla is 32 now, a venerable midfield skill-goblin with 12 full seasons in Spain and England behind him. The fear, hopefully unfounded, is that this might in effect be it, that a player who has always dodged around his own physical limits might have reached a point where twanging tendons and straining fibres begin to intrude decisively.

For most of the last year Cazorla has been a significant, but often unmentioned absence. In the litany of Arsenal-isms, that Lord’s prayer of failings it is necessary to recite when discussing the stagnations of Arsène Wenger’s team – no leaders, Clive; gone soft, Clive; major shareholders created a culture of existential corporate alienation, Jeff – the Cazorla-shaped hole is usually quite far down the list. Which is odd in itself, as not only is he Arsenal’s most technically complete player. Cazorla is also arguably, and in glimpses, the best central midfielder in the Premier League.

Naturally statements like these are likely to induce a familiar haze of spittle-flecked outrage. But it is also easy to forget what a successful rejig Santi-in-the-middle has been in the last few years. When Cazorla plays as he can it is hard to think of a Premier League midfielder who can control a game with such persuasive craft and urgency.

Just as it is unlikely any English team will see a better all-round performance this season than Cazorla’s outflanking of that powerful Paris Saint-Germain midfield in the second half in Paris last September, scuttling about, holding the ball in tiny spaces and driving the game back Arsenal’s way like a plucky little snowspeeder patiently winding its guy rope around the legs of the imperial walkers. Most of all Cazorla is just great fun to watch. On one hand he looks like an utterly modern, technically complete two-footed footballer. On the other he’s a titchy, Penfold-ish presence, resembling even as he jinks and sways and burrows into space not so much an elite streamlined modern athlete as a very clever, cheerful cartoon mouse who knows how to play the banjo and keeps sugar lumps in the pocket of his waistcoat.

Of course, none of this is exactly a secret. Real Madrid have tried to buy Cazorla twice. He has 77 caps for Spain, where his skills have long been drooled over, not to mention two European Championship winners’ medals. And yet it has still been Cazorla’s fate to be a little undervalued. Perhaps the frustration is that those glimpses in that slightly altered central role have been so brief. In England at least, where Cazorla has spoken of his fascination with seeking out space beyond the first rush of pressing and marking, he might just have found a perfect central role a little late in life.

Football’s structures are a little more fluid these days. Recently Demarai Gray has impressed for Leicester in a role that seems to involve picking up possession and sprinting 60 yards in a straight line – Midfield Ball-Running Man, Downfield Sprint Bludgeon – in effect acting as a kind of human long-ball, punt downfield made flesh.

Cazorla’s central role is a minor variation, the use of a deep ball-playing midfielder a response to the condensing effects of the Premier League’s game of sprints and hustles. One of the minor pleasures of Chelsea’s season has been Cesc Fàbregas’s occasional appearances there, louche and stubbly and half-speed, but with a startling note of poise in his passing. Juan Mata is still hobbling around like a bandy-legged little horse. Across the city at the Etihad Stadium this week David Silva was mesmerising again, faced with the superior power and reach of Monaco’s hulking midfield.

With Cazorla in the centre Arsenal are a different team. Mainly they’re a better one, his presence above all defensive and stabilising, a leadership role. This season Cazorla has started 10 games, with eight wins and two draws. Arsenal have kept five clean sheets with him in the team, compared with four in 20 League and Champions League games since his injury. In the last five years Arsenal have beaten Chelsea, Manchester United, Manchester City, Liverpool and Tottenham just once without their most resilient ball-hog in the team.

As this late-Wenger team continues to twitch and flicker and quietly congeal towards its endgame there are, of course, many strands to the story. In Cazorla’s absence the sense of a moment passing, of possibilities lost, abandoned trails, is tangible.

The Guardian Sport