Last month, Geir Lundestad, the former secretary of the Nobel Academy broke the august body’s traditional reserve to express his deepest regrets in having awarded Barack Obama the Nobel Peace Prize in 2008. “That was a big mistake,” Lundestad lamented.

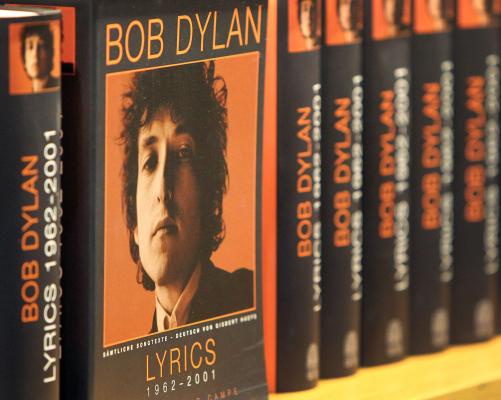

Should we expect a similar apology, maybe in eight years’ time, about the choice of the 1960s pop star Bob Dylan as this year’s Laureate for Literature? The comparison may not be exact, as comparisons seldom are.

Obama was given the prize when he had done nothing in particular to promote peace or anything else except himself. By contrast, Dylan has a body of work in the form of dozens of popular songs of which he has authored both the lyrics and the music.

And, yet, to claim his work as literature may be both confused and confusing. Dylan is a singer-songwriter and as such belongs to the universe of music and not literature. Remember that there are seven arts: paintings, sculpture, architecture, music, dance, literature and, thanks to the Lumiere Brothers, cinema. In recent years, people have tried to add other categories such as comic strips, lithography, television drama, and, of course, journalism.

However, regardless of how many categories of art one comes up with, there is an old consensus that poetry is at the heart of every art form. It was no accident that Aristotle, the father of all categories, named his treatise on the whole of literature as “Poetics”. The ideal man, if he ever existed, would live life poetically (poesitai in Greek).

“The essence of all art is poetry,” writes Heidegger. “And the essence of poetry is the instauration of the truth.” Surely, even the Nobel Academy must know that Bob Dylan does not belong to the same category as Tomas Transtromer, the Swedish poet who was given the prize in 2011.

Some art and/or sub-art forms either require text or seek to deepen their impact by the use of texts. Opera, the queen of music, uses libretti to narrate its story. Films require screenplays. Chunks of sacred texts are also used in some architectural forms, notably in Islamic lands and the Indian Subcontinent. Literature, however, is complete in itself, needing no support from other art forms. A poem could, of course, be recited in a dramatic way (declamation) or even accompanied by music. But even without such accompaniment, it would be complete.

The question is whether Dylan’s songs could be regarded as poetry. My answer is: “No”. That does not mean that Dylan’s work is without merit. On the contrary, he is one of the most talented singer-songwriters I know in the few languages I follow. Those of his songs, for example “Corina, Corina” or “Honey! Just Allow Me One More Chance”, that came closest to poetry, are the works of others.

Dylan is not as genial as Charles Trenet, Georges Brassens or Leo Ferre. But he certainly stands with John Lennon, the Gibb brothers, Leonard Cohen and Elton John. All of them belong to a very ancient and highly valued branch of music that uses words to tell a story or describe a mood. Many languages have special words for them. In old French they were known as the troubadours who had learned their art from the Arabs during the Crusades, playing the oud , a string instrument that was to evolve into the European guitar. The Arabs call them “qawwal” or “mughanni”. To Persians, they are “lulis” and Turks know them as “Ashiq”. The word for them in English is “minstrel” and in Burmese “nat”.

That they belong to a tribe distinct from poets has always been admitted. The Latin poet Horace regrets that he cannot write a song for his beloved. Amaury, the 13th century French troubadour is sad that he is not a real poet to describe the beauty of lady Adelaide.

There are also special words for those who write words for music. In Persian they are called “taranehsara”, in French “parolier” or “chansonnier”, and in English “lyricist”.

The art of songwriters and writers of libretti for opera need not be considered of lesser value than that of poets. In fact, in the days when Vienna was world capital of culture, someone like Hugo von Hofmannsthal was better known for the libretti he wrote than for his poetic oeuvre. Sometimes, poets were even jealous of songwriters. In the 1920s, the great Persian poet Iraj Mirza lampooned his friend-cum-rival Aref Qazvini for being “a mere songwriter” and yet more popular with the public.

It is not the first time that the Nobel prize-givers have stuck the label “literature” on work that belongs to other categories. For example, they gave the literature prize to Dario Fo, a highly talented Italian stand-up comedian who compared well with George Burns to Raymond De Vos but was certainly no literary writer. The 2004 laureate Elfriede Jelinek of Austria is an interesting pamphleteer closer to journalism than to literature. Last year’s laureate Svetlana Alexievich is also a journalist whose work, though outstanding in its own category, cannot be regarded as literature.

Rather than labelling everything literature, the Nobel Academy might do well to establish prizes in other categories such as stand-up comedy, song-writing, journalism, pamphleteering and even limericks.

In medieval scholasticism, mixing the genres (in Arabic theological lexicon: khilt al-mabhath) was regarded as a grave error of judgment. Nowadays, however, our obsession with equality leads us to believe or at least claim that any categorization might mean inequality and apartheid. While we celebrate “difference” and “otherness” as intrinsic values we also want all those who are “different” and “other” to fit into exactly the same pattern.

Is it not possible to celebrate and honor the creators of culture, which means whatever man adds to nature, in their own categories and according to their “excellence” (“Arete” in ancient Greek and “Ann” in Persian)? Isn’t it enough for Bob Dylan to be an outstanding singer and songwriter who does not need to be re-packaged as a poet?

Anyway, here is an amateurish limerick for good old Bob’s 76th birthday:

“Whatever tells you the academy

You are a man of do re mi

And not the poet they say you are

You come close, but no cigar.”